This article was first published in the 25th issue of Manushi in 1984.

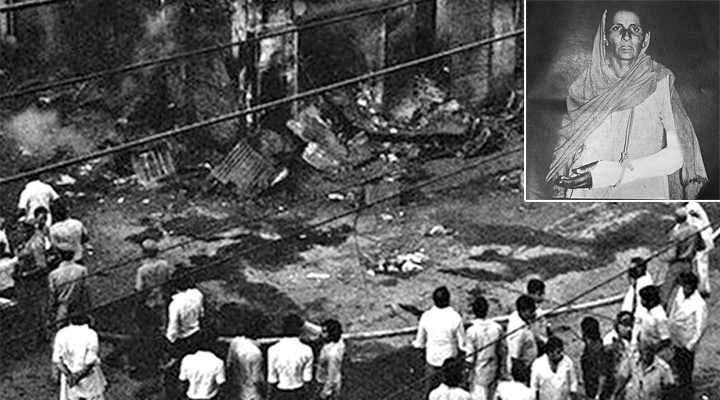

In the aftermath of Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984 by two Sikh security guards, North India witnessed the most gruesome anti Sikh massacre.

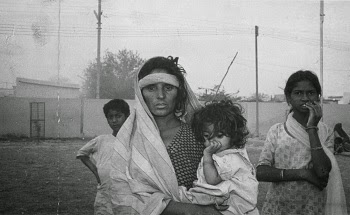

The following report entitled “Gangster Rule: Massacre of the Sikhs in 1984” was written on the basis of my first hand exposure and interviews with the survivors of and witnesses to the anti Sikh pogrom that engulfed Delhi and large parts of North India starting 31st October 1984– the very morning that Indira Gandhi was assassinated. This report was published in issue no 25 of MANUSHI.

The mayhem lasted till the 3rd of November 1984. Over 10,000 Sikhs were allgedly put to death in gruesome ways in different towns and cities of North India. In Delhi alone, over 3000 Sikhs were burnt alive and numerous women sexually brutalized, though at the time, the Government claimed only 600 had died.

At the time, the media had projected the killings in North India as fallout of Hindu Sikh “riots”. However, Manushi challenged this description and argued that a riot presupposes two or more communities attacking each other. There was no retaliatory violence on the part of Sikhs because they were altogether unprepared for the onslaught. Since the killings were one way, it could only be called a “massacre”.

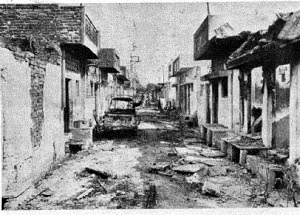

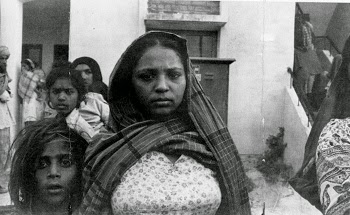

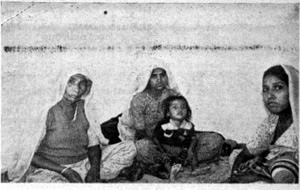

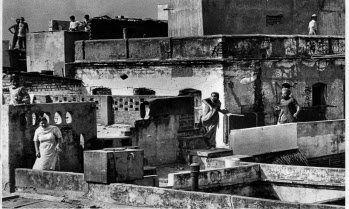

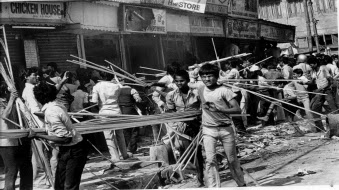

Most of the photographs accompanying the article were taken by the author on an amateur camera.

__________________________________________________________

The communal violence that followed Indira Gandhi’s tragic death on October 31 were like the sudden eruption of a gigantic volcano. The ferocity of the explosion took by surprise both the victimised community and the community in whose name the ferocious campaign of looting, arson, killing, burning, rape and molestation took place.

Most observers agree that the violence began as random attacks on individual Sikh men who were pounced upon in public places, on public transport and on the streets on October 31. The events of this day may have been passed of as a spontaneous outburst of anger at the assassination of Indira Gandhi by two Sikh members of her security guard. But what happened over the next three days makes it impossible to dismiss those events as spontaneous expressions of outrage.

The series of attacks on Sikh homes, gurudwaras and commercial establishments which began on November 1 seems to have been the work of organised hoodlums who collected large mobs for the looting and killing spree. Very broadly speaking, the attacks can be placed in three categories,

- Looting and killing in middle and upper middle class localities, such as Lajpat Nagar, Jangpura, Defence Colony, Friends Colony, Maharani Bagh, Patel Nagar, Safdarjung Enclave and Punjabi Bagh. Here, houses, gurudwaras and shops were looted and burnt, and a large number of vehicles, including buses, trucks, cars and scooters were set ablaze. Some people were injured and others killed.But, on the whole, relatively fewer lives were lost in middle class colonies.

- The systematic slaughter and rape that accompanied looting, arson and burning in the resettlement colonies, slums and villages around the city. Most of the death occurred in areas like Trilokpuri, Kalyanpuri, Mangolpuri, Sultanpuri, Nand Nagri, Palam village, Shakurpur, Gamri. Rows of houses and huts were burnt down and hundreds of men and young boys were beaten, stabbed and burnt to death while many women were abducted and raped. A large number of persons are still reported missing by their families. Houses and gurudwaras were looted and burnt down.

- Sikh men and boys were attacked in the streets, trains, buses, markets and workplaces, and many of them brutally murdered, some of them burnt alive or thrown out of trains. Others escaped with injuries, more or less serious. This kind of attacking seems to have been done at random -any man who looked visibly Sikh was made a target.

Most of the observations in this article are based on several taperecorded interviews with men and women from some trans-Yamuna colonies, especially Trilokpuri. These were among the worst hit areas in Delhi. Some other observations are based on what I saw happening in our neighbourhood, Lajpat Nagar, and on conversations with our neighbours as well as with friends living in different middle class colonies in the city. The pattern of murder and arson was similar in most parts of Delhi, in as farflung places as Palam village, Mangolpuri, Kalyanpuri, and Bhogal. However, the intensity of violence was far more severe in poorer resettlement colonies than in middle class areas.

Among the worst hit: Trilokpuri is one of those resettlement colonies which were brought into existence during the emergency, when Sanjay Gandhi spearheaded slum clearance drives in Delhi. Thousands of families were forcibly evicted from slums and unauthorised colonies in the city. They were transported to areas several miles away from the city proper, and were resettled there. Each evicted family was supposed to be given a small plot measuring 25 square yards, and in some cases also a loan to build a house. Thus were founded these colonies of the city poor who had been evicted from the slums and pavement dwellings where they earlier lived.

Even though, at that time, many people saw the evictions as cruelty inflicted on the city poor, the Congress (I) was able to convert the resettlement colonies into solid support bases and vote banks, because the evicted families slowly began to feel that their status had been considerably boosted since each of them now owned a piece of land and a pukka house, instead of living as formerly in unauthorised structures in slums. Many of the riot victims interviewed, who were amongst the original recipients of land, mentioned that they were very grateful to Indira Gandhi and to her party for this favour. However, many of those who were given plots of land sold them off, because the resettlement colonies are very far away from the city proper, where most poor people have to come daily to earn a living. Many lower middle class families bought plots of land from the original allottees. Thus, today, the social composition of these colonies provides a rich mixture. For instance, in Trilokpuri, one finds North Indians and South Indians, Hindus, Christians and Sikhs all living cheek by jowl.

The occupations range from petty shopkeeping to business to domestic service to low level government employment to rickshaw pulling, scooter driving, peddling and artisanry. In normal times, there seems to be a good amount of intermingling and friendly feeling between neighbours of different communities, even among those who speak different languages. Yet the feelings about high and low status are also pronounced.

Among Trilokpuri Sikhs, too, there are significant variations. A large number of them, especially those most severely affected by the riots, are known as Labana Sikhs. These are not Punjabi Sikhs. They are migrants from Sikligarh in Sind, now part of Pakistan. They speak either Hindi or their own dialect, which is distinctly different from Punjabi. The traditional occupation of the community is weaving string cots and pounding rice. Few of the men still perform these jobs. Most of them have switched over to other occupations. A number of them drive scooters and pull rickshaws. Some work as porters at different railway stations. Others have taken to working as mechanics, carpenters and construction workers. A few have been to Gulf countries as skilled labourers.

Even though they do not call themselves Mazhabi Sikhs, they are considered low caste by other Sikhs. Makhan Bai of Trilokpuri summed up the distinction aptly. Referring to urban based Sikhs, most of whom are involved in commerce, she said : “Punjabi Sikhs are Seths. We Labana Sikhs are labourers. Traditionally, we are charpai makers.”

Differences are visible even amongst the Labana Sikhs in this colony. Those who have entered some of the newer occupations such as scooter driving or mechanical repair work are relatively belter off. They have pukka houses and their own plots of land. They are an upwardly mobile community. Many of them own television sets, tape recorders and other such consumer items. However, those who were not able to move into these new occupations are much poorer. Some of them live in huts constructed illegally in open spaces which are meant to be parks.

Labana Sikhs live together in clusters in blocks 30 and 32 of Trilokpuri. There are also some families scattered in other blocks.Labana Sikhs have a separate small gurudwara of their own. There is also a big gurudwara adjoining the main road in Trilokpuri. The Labana Sikh community seems to have very little connection with Punjab politics. Many of them are traditional Congress (I) supporters. That is one reason why they, like most Sikhs in Delhi, were taken totally unawares by the attack.

Initial resistance by Sikhs: Far more than 400 people were murdered in Trilokpuri alone. The largest number of deaths has so far been reported from the two blocks of Trilokpuri where the Labana Sikhs were concentrated. This is how Gubar Singh, a resident of block 30, Trilokpuri, describes the events of November 1 : “My house was the first to be burnt in Trilokpuri. I work for a tailor’s shop. I bring the material from the shop every morning and stitch the garments at home. On the 31st, when I was on my way back from the shop, I heard rumours that Indira Gandhi had died. But no one stopped me or tried to hurt me. I never imagined that such a thing could happen to me. None of us was really prepared for what happened the next day.

“At about 10 a.m. on November 1, we heard a lot of noise and shouting. We climbed on the roofs of our houses to see what was happening. We saw smoke rising from Noida colony and then we smelt human flesh burning. In the meantime, we heard people say that the mob, having set fire to the main gurudwara, was now coming to burn our Labana Sikh gurudwara. So we rushed and got together whatever weapons we had, and tried to save the gurudwara. But even when the gurudwara was attacked, we thought there would be fighting for a short while, and then the police would come and stop it. We never thought things would go so far. There has been no atmosphere of conflict between Hindus and Sikhs in Trilokpuri.

“Several men from our block went and hid in other lanes nearby. So we were not more than 500 men left to defend the whole block as well as the gurudwara. About 50 of us stood on each side of the streets in our block. The attackers came in a mob about 4,000 strong, and began an attack on the gurudwara. They were armed with lathis. They began throwing bricks and stones at us. We also stoned them. See, my fingers are cut with throwing bricks. Many of us got hurt. Heads were split open. The attackers far outnumbered us. Gradually, we had to give up. They advanced and we began to retreat into our houses. They set fire to the gurudwara.

Self defence scattered: “Then they began to attack our houses. We ran from one house to another, trying to save ourselves. They broke into each house and carried away all our possessions on thelas. There were about four policemen watching this looting campaign. They told us to put down our swords and not to worry. They said: ‘Nothing will happen to you.’ Then they went away and left us to be killed.

” Sajan Singh from block 32 adds that the attackers had three guns. The police kept telling the Sikhs to go into their houses and assuring them that peace would be restored. “We believed the police and we went in. That is how they got us killed.” He accuses the SHO of the area, one Tyagi, of having actively encouraged the attackers. Many others of the area also testify that they heard Tyagi tell the attackers: “You have three days to kill them. Do your job well. Do not leave a single man alive, otherwise I will have to suffer.”

Seeking hiding places: Once the attempt at group defence was broken down, they were in a much more vulnerable position. Each man ran desperately to find for himself a hiding place from the mob. Gulzar Singh continued his narrative:”By the evening of the 1st, some peace was restored. The attackers left. They threatened that they would return the next day and would take away the women. Several men died on the 1st. About half a dozen died in my presence. The attackers hit them with lathis and khurpis. They also managed to snatch some of our kirpans and stabbed some of us with them. When they were looting and burning my house, they laid hands on me. They burnt part of my hair and cut part of it before I managed to break free.

“I saved myself by hiding in my brother’s house which is in a Hindu street. For one day and two nights, my brother and I hid under a double bed. On the 2nd, a group of men came and began to search each house for Sardars. My wife says three men were caught and killed in the neighbouring house. The attackers turned everyone out of the house and searched it. We were hiding behind boxes and bags under the bed. They kicked the boxes and thought there was no one there. Another minute and we would have been finished.

“On the 3rd, the military came and my wife told them to rescue us. That is how we reached the relief camp. One of my brothers was found by the attackers and killed on the 2nd. They threw him down from the roof of his house and broke his spine. Then they burnt him alive. Many women were molested and abducted. I saw a jeepload of women being carried away to village Chilla in the presence of their families.”

Most others who survived had been through similar experiences. The attackers would kill every Sikh male in sight, would leave for a while, but would return again to search Sikh houses and neighbours’ houses to finish off those men who were still in hiding.

Sajan Singh, who works as a porter at Nizamuddin railway station, and lives in block 32, Trilokpuri, was also a victim of the clashes. He saved himself by hiding in his house, in a small aperture where cow dung cakes used to be stored for fuel. The attackers came in repeated waves into his house and looted everything they could find. He says he had Rs 12,000 in cash, a television set, a radio, a tape recorder, utensils, eight quilts, blankets and other household goods, many of which were being stored up as dowries for his four daughters. At night, the attackers came with torches to search for men who were still hiding. Sajan got his children to bring him a pair of scissors and a stick. He cut off his long hair and beard while he was hiding under the cow dung cakes. Then, he says : “When the next wave came, I picked up a stick and mingled with the mob. All night, I shouted anti Sikh slogans like ‘Kill the Sardars.’ That is how I saved myself. At 6 a.m., I somehow managed to slip away and came to Nizamuddin railway station. There, the other porters gave me shelter and consoled me. I did not know what had befallen my family. On the 6th, I came to Farash Bazar relief camp and found them there. My sister has been raped. The other women and children are safe.”

Many of these one sided battles continued for hours on end. The woman neighbour of a victimised family in Shakurpur described the attack : “The mob came here on 31st night, and the fighting continued till the 2nd. The terror began on the 31st. The attackers began by stopping vehicles to check if there were Sikhs in them. Electricity failed in this area, in the houses as well as on the streets. The extreme darkness at night heightened the terror. The attacks on houses and gurudwaras started around 9.30 a.m. on the 1st. They came and started stoning the house of our neighbour, Santokh Singh. The family stayed quiet inside the house. The crowd wanted to enter the house but was hesitant, afraid of possible resistance. People are generally afraid of Sikhs, you know. Finally, one of the men tried to break into the house. The men of the family hit him with a sword and his hand got slightly cut. This frightened the crowd and they retreated for a while. Then they slowly collected more men and returned. Now they were about a 1,000 men. They dragged some furniture and wood that was lying in Santokh Singh’s courtyard, piled it up around the house, and set the house on fire. Then, the four men of the family came out with swords in their hands The attackers immediately ran away. They did not want to take any risk. They were armed only with lathis and kerosene. But they soon advanced again and started stoning the house from all sides. The house was now burning. The four men of the family ran for their lives. One went to the house of a neighbour who cut his hair, gave him shelter and later smuggled him out of the colony. The youngest son was pounced upon on the road, hit with lathis and burnt to death. Another son is missing. Most probably, he was murdered by the same group. We do not know what happened to him. After some time the police came and took away the old father and the women to a camp. They have not yet arrested anyone.”

So murderous were the attacks throughout the city that most of the men who fell into the hands of the mob did not survive. The number of injured men was very small in comparison to the numbers killed. Many others were less fortunate. One old man, Gurcharan Singh, also from block 32, lost all the three young men of his family. He had only one son, aged about 17, and two nephews, aged 20 and 22. All four men stayed in hiding for two days and one night. Finally, the door of the house was broken open. The four men had already clipped their beards and cut off their long hair. They came out and pleaded to be spared now that they were like Hindus. But the rioters caught hold of the three young men, threw them on their own string beds, covered them with mattresses and quilts, then poured kerosene over them and set them on fire in Gurcharan Singh’s presence. Gurcharan Singh was beaten up. He and his aged wife, who is a TB patient, are in the relief camp, despairing over the loss of their three sons, and destitute.

Deliberate, unhurried murder squads on hire: Most people in Trilokpuri said though their immediate neighbours were not amongst the attackers, a fair number of rioters were from other parts of the same colony. They identified these men as Chamars, Sansis, Gujjars, Muslims and Gujjars (Muslims are also Gujjars). The last named had been specially brought in for the attack that morning from Chilla, an adjoining village, they said.

Many eyewitnesses confirm that the attackers were not so much a frenzied mob as a set of men who had a task to perform and went about it in an unhurried manner, as if certain that they need not fear intervention by the police or anyone else. When their initial attacks were repulsed, they retired temporarily but returned again and again in waves until they had done exactly what they meant to do -killed the men and boys, raped women, looted property and burnt houses.

This is noteworthy because in ordinary, more spontaneous riots, the number of people injured is usually observed to be far higher than the number killed. The nature of the attack confirms that there was a deliberate plan to kill as many Sikh men as possible, hence nothing was left to chance. That also explains why in almost all cases, after hitting or stabbing, the victims were doused with kerosene or petrol and burnt, so as to leave no possibility of their surviving. Between October 31 and November 4, more than 2,500 men were murdered in different parts of Delhi, according to several careful unofficial estimates.

Gang rapes and abduction of young women: There have been very few cases of women being killed except when they got trapped in houses which were set on fire. Almost all the women interviewed described how men and young boys were special targets. They were dragged out of the houses, attacked with stones and rods, and set on fire. In Trilokpuri, many women said that once the attack on individual homes started, the attackers did not allow any women to remain inside their own homes. The attackers wanted to prevent the women from helping the men to hide or providing assistance to those who were in hiding. Throughout this period, many of the women were on the streets.

When women tried to protect the men of their families, they were given a few, blows and forcibly separated from, the men. Even when they clung to men, trying to save them, they were hardly ever attacked the way men were. I have not yet heard of a case of a woman being assaulted and then burnt to death by the mob. However, many women were injured when they tried to intervene and protect the men, or in the course of molestation and rape. A number of women and girls also died when the gangs burnt down their houses while they remained inside.

This is seemed odd. When I asked why the killing was so selective, I got a uniform answer from most people interviewed : “They wanted to wipe out the men so that families would be left without earning members. Also, now they need not fear retaliation even if we have to go back and live in the same colony.” Though this may not provide a complete explanation, the effect has been exactly that which the women describe.

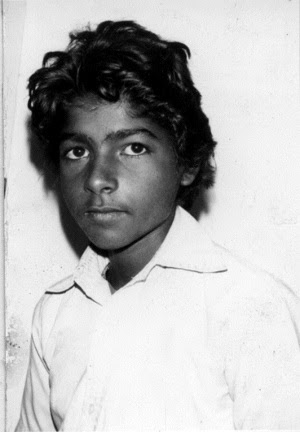

In many cases, families tried to save adolescent and little boys by dressing them up as girls and tying their hair in loose hanging plaits. Sometimes, neighbours pointed out these disguised boys to the attackers. When such boys were caught, they were, pounced upon by the crowd and set on fire. However, a few, especially very young ones, did manage to escape death by assuming this guise.

Sukhpal Singh is one of the few older boys of Trilokpuri who was able to escape by dressing as a girl even though he is 15 years old. His family lives in block 19 but on that fateful morning, his parents sent him to his sister’s house in block 30 because they felt he would be safer in the latter area where Sikhs lived together in a large cluster. Sukhpal’s brother-in-law sought shelter in a Sikh house but he was turned out. The mob caught him on the second floor of a house, threw him down and burnt him alive. Sukhpal Singh’s sister dressed him up in girl’s clothes and braided his long hair like that of a girl. Somehow, he managed to escape attention and discovery.

In most camps, there is a disproportionately large number of women and children. Among boys, most of those who managed to escape were little ones. According to figures collected by Nagrik Ekta Manch volunteer Jaya Jaitley, out of about 539 families housed in Farash Bazar camp, there are 210 widows. Families which have lost all adult male members are the ones most afraid of going back to the colonies where they formerly lived. Most do not want to go back even to claim their plots of land, and would rather be settled elsewhere.

Even though most women were not brutally murdered as were men, they were subjected to other forms of torture, terror and humiliation. This part of the story also makes familiar reading for anyone who has gone through accounts of riots, communal clashes and wars.

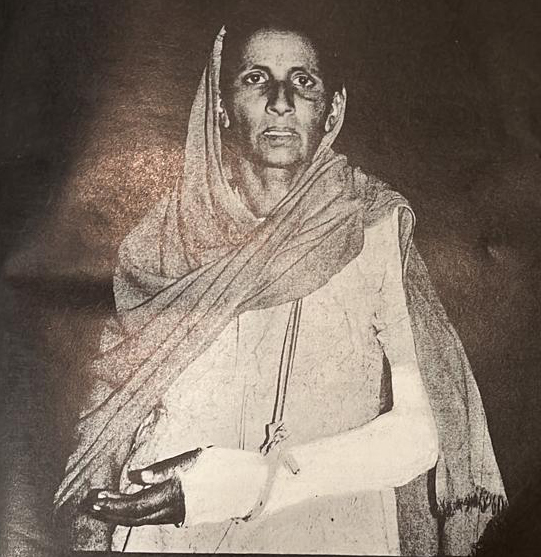

Gurdip Kaur, a 45 year old woman from block 32, Trilokpuri, told a typical story. Her husband and three SONS were brutally murdered in front of her. Her husband used to run a small shop in the locality. Her eldest son, Bhajan Singh, worked in the railway station, the second in a radio repair shop and the third as a scooter driver. She says : “On the morning of November 1, when Indira Mata’s body was brought to Tin Murti, everyone was watching the television. Since 8 a.m., they were showing the homage being paid to her dead body. At about noon, my children said: ‘Mother, please make some food. We are hungry.’ I had not cooked that day and I told them : ‘Son, everyone is mourning. She was our mother, too. She helped us to settle here. So I don’t feel like lighting the fire today.’ SOON after this, the attack started. Three of the men ran out and were set on fire. My youngest son stayed in the house with me. He shaved off his beard and cut his hair. But they came into the house. Those young boys, 14 and 16 year olds, began to drag my son out even though he was hiding behind me. They tore my clothes and stripped me naked in front of my son. When these young boys began to rape me, my son began to cry and said: ‘Elder brothers, don’t do this. She is like your mother just as she is my mother.’ But they raped me right there, in front of my son, in my own house. They were young boys, maybe eight of them. When one of them raped me, I said : ‘My child, never mind. Do what you like. But remember, I have given birth to children. This child came into the world by this same path.’

“After they had taken my honour, they left. I took my son out with me and made him sit among the women but they came and dragged him away. They took him to the street corner, hit him with lathis, sprinkled kerosene over him, and burnt him alive.I tried to save him but they struck me with knives and broke my arm. At that time, I was completely naked, I had managed to get hold of an old sheet which I had wrapped around myself. If I had had even one piece of clothing on my body, I would have gone and thrown myself over my son and tried to save him. I would have done anything to save at least one young man of my family. Not one of the four is left.”

According to her, hardly any woman in her neighbourhood was spared the humiliation she underwent. She said even nine to 10 year old girls were raped. She was an eyewitness to many such rapes. The attackers first emptied the houses of men who were burnt alive. After that, they dragged the women inside the ransacked houses and gang raped them.Not many women would openly admit this fact because, as Gurdip Kaur says : “The unmarried girls will have to stay unmarried all their lives if they admit that they have been dishonoured. No one would marry such a girl.” Therefore, most families do not openly acknowledge the fact.

This led me to ask Gurdip Kaur why she had come forward to narrate her experience. I also asked whether she wanted me to publish her statement. She categorically said she wanted her statement to be published : “Those women in whose homes there is one or more surviving men cannot make a public statement because they will be dishonouring those men. I have no one left (meaning no male member). My daughter has also been widowed. She has two children. My daughter-in-law, who has three children, has also been widowed.Another daughter-in-law was married only one and a half months ago and has also been widowed. I have nothing left. That is why I want to give my statement.”

In fact, many other families whose adult men had all been killed similarly felt that there was “no one left in the family.” At times, when people said that all their children (bachey) had been killed, they were actually referring only to their sons. I had to specifically enquire about surviving daughters, whose lives were not counted in the same way.

Indra Bai narrates : “At about 4 p.m., after they had murdered all the Sikh men they could get hold of in our block, they asked the women to come out of the houses. They said : ‘Now your men are dead. Come out and sit together or else we will kill you too.’

“We women all huddled together and they offered us some water. As we were drinking water, they began dragging off whichever girl they liked. Each girl was taken away by a gang of 10 or 12 boys, many of them in their teens. They would take her to the nearby masjid, gang rape her, and send her back after a few hours. Some never returned. Those who returned were in a pitiable condition and without a stitch of clothing. One young girl said 15 men had climbed on her.”

Gurdip Kaur and many other women from Trilokpuri whom I interviewed at Balasaheb gurudwara and at Farash Bazar camp also talked about several women who had been abducted by gangsters and taken to Chilla village which is dominated by Muslims/Gujjars some of whom are alleged to have led the attacking gangs. On November 3, the military brought some of these women back from Chilla. But many of them were untraceable at the time I interviewed these families. They were very worried that these women had either been murdered or were still being held captive.

Rajjo Bai, another old woman from the same neighbourhood, who had sought shelter in Balasabeb gurudwara in Ashram, had a similar tale to tell. Two of her sons were killed in her presence. One who was hiding in a hut is still missing. All three sons were rickshaw pullers. She got separated from her two daughters-in-law who were probably abducted. The daughters-in-law were found much later at the Farash Bazar camp but Rajjo’s 24 year old daughter, who had had to be left behind in the house because she was disabled, could not be traced.

Nanki Bai, also from Trilokpuri was distraught when she asked us to look for her daughter, Koshala Bai, who had been snatched away from her. She says : “All night, the attacks continued. My husband was hiding in a trunk. They dragged him out and cut him to pieces. Another 16 year old boy was killed in front of my eyes. He was carrying a small child in his arms. They killed the child too.

“We women were forced to come out of our houses and sit in a group outside. I was trying to hide my daughter. I put a child in her lap and dishevelled her hair so that she would look older. But finally one of our own neighbours pointed her out to these men. They began to drag her away. We tried to save her. I pleaded with them. My son came in the way and they hit him with a sword. He lost his finger. I could not even look at his hand. I just wrapped it in my veil.

“They took Koshala to the masjid. I don’t know what happened to her. At about 4 a.m., when we were driven out of the colony, she called out to me from the roof of the masjid. She was screaming to me : ‘Mummy, mujhe le chal, mujhe le chal, Mummy.’ (take me with you). But how could Mummy take her ? They beat her because she called to me. I don’t know where she is now.”

Later, I met Koshala in the Farash Bazar camp and told her that her mother was in Balasaheb gurudwara. She confirmed her mother’s account and added that her father’s eyes had been gouged out before he was killed. But she did not say that she had been raped. She merely said : “They slapped me and beat me and struck me with a knife. They tore up my clothes.”

The rapists made no distinction between old and young women. In Nand Nagri, an 80 year old women informed a social worker that she had been raped. In Trilokpuri, several cases were reported of old women who were gang raped in front of their family members. As in all such situations, the major purpose of these rapes seems to have been to inflict humiliation and to destroy the victims’ morale even more completely.

Manchi Devi, about 55, says she was gang raped. Four men of her family, including her son-in-law and her nephew, were murdered. “When I tried to intervene to save the children, several of those men grabbed me. Some tore my clothes, some climbed on top of me. What can I tell you, sister ? Some raped me, some bit me all over my body, and some tore off my clothes. All this happened around 11p.m. in my own house. I don’t know how many men there were. The whole house was full of them. About a dozen raped me. After that, they caught hold of some young girls outside. My old husband and one nine year old son are the only ones left in my family. Whom shall I depend on in my old age ? What can this nine year old do?” Most of these rapes took place while the bodies of the husbands, sons or brothers of these women were still smouldering in their presence, and their homes had thus been converted into cremation grounds.

Baby Bai, a young bride, aged around 20, was also gang raped. She was married barely a year ago. Her husband was a rickshaw puller, and sometimes worked as a scooter driver. She says : “There were six members in our family. The three men, my husband and my two brothers-in-law, were murdered. Now only three women are left. Our house was attacked at about 4 p.m. and the fighting continued until next morning. My husband was first beaten and then burnt to death, I was sitting and crying when a big group of men came and dragged me away. They took me to the nearby huts in front of block 32, and raped me. They tore off all my clothes. They bit and scratched me. They took me at 10 p.m. and released me at about 3 a.m. When I came back, I was absolutely naked, just as one is when one comes out of the mother’s womb. They took away all my jewellery-ear rings, a gold chain, bangles, nose ring and anklets. They left without giving me anything to cover myself. On the road, I found someone’s old sheet. I wrapped myself in it and walked up to Chilla village. There, I borrowed some clothes from my relatives.”

Pyari Bai, aged about 70, has also lost all the male members of her family-three sons, a grandson, two sons-in-law and two nephews. Most of the men in her family used to weave string beds for a living and one was a rickshaw puller. Her daughter-in-law, who is several months’ pregnant, was dragged inside the house and raped. Pyari Bai too says that not even old women or little girls were spared.

Even though it was widely known that these attacks had been going on unabated since November 1, the government neither provided the victims with any physical protection nor made any arrangements for them to be evacuated until much after the worst was over.

Women prevented from registering rape cases: Most of the women, especially those who had some surviving male members in their family, were not willing to say they had been raped although most of them did talk about women in general having been abducted and raped. They were pressured into staying silent about their personal experience not merely by the threat of social ostracism within their own community such as being abandoned by husbands or not finding husbands if unmarried; other outside pressures played an important role, too.

Gurdip Kaur narrated how the raped women in Farash Bazar camp were prevented from even getting a routine medical examination and registering a complaint. A few women did come forward to get cases registered. Some of the doctors of the medical relief team also confirmed that several such women had come to them, but since rape cases are considered medico-legal cases for which special evidentiary procedures have to be followed, the women had to be referred to a hospital by the government administration doctor who was posted at the camp. This, however, did not happen.

Gurdip Kaur said: “Most of the women who went to register a case were young, unmarried women. Four of them were sent into the doctor’s room. I was asked to wait outside. The women who went inside were intimidated by those in charge and were warned not to undergo the medical examination. They were told that hands would be shoved up their vaginas and much else would be done to them. They, being young, inexperienced women, got frightened,and did not insist on a medical examination.” Gurdip Kaur regrets that she was not allowed to be with them and encourage them. Hence no case was registered.

Gurdip Kaur says she heard that H.K.L. Bhagat was coming to Farash Bazar camp. She tried to give him her statement but she could not meet him. The physical violence that these women experienced is going to be buried in their hearts as their own “shame.” Several men of their community who were living in the camp talked to me of these “dishonoured” women, who had been forced to do a “wrong action” and whose lives were now worthless. Thus, it seems to me very unlikely that they will be treated even by their own community with any measure of the sympathy and understanding that the male victims of violence received.

Women left destitute: In Trilokpuri, very few Sikh women work for a wage. Thus, the families are left with no male members and are also without wage earners. Widowed women constitute the most vulnerable group amongst the surviving victims of the carnage. Many of them are illiterate or barely literate. Few have any skills at all. Very few have ever worked outside the house. Most of the women have several young children so that going out of the house for long hours to earn a living may not be feasible.

Thakari Bai, who is in her early twenties, is typical of such women. Her husband worked as a coolie at the railway station and earned more than Rs 50 a day. She has three daughters, aged seven years, three years, and two months. One of them is disabled and retarded. In tears, she told us that her three brothers-in-law, who managed to survive by cutting their hair and hiding, now do not wish to support her. Already, they and their families have begun to ill treat her and quarrel with her, because they fear that she and her daughters will become a burden on them. She says her widowed mother, who lives in a Rajasthan village, is very poor. Her mother works as a labourer and often has not enough to eat. So Thakari Bai does not know where she will go if the relief camp forces her out without some means of livelihood and accommodation being provided to her.

Several relief workers reported that fierce tensions had sprung up between daughters-in-law and mothers-in-law over the question of who should receive the Rs 10,000 promised by government as compensation for a dead man who was the son of one woman and husband of the other. Given the fact that neither wives nor mothers have any independent sources of income and all can only look forward to destitution, the conflict appears to be inevitable.

One Way Battle: Much has been made of the so called provocation offered by Sikhs who came out with swords and kirpans, as at the Trilokpuri gurudwara. But all available eyewitness accounts confirm that swords, if used at all, were used as a desperate measure of self defence, when no other help was available. Either the police was not present or if it was present it was playing the role of passive onlooker or active abettor.

We would also do well to remember that the Indian Penal Code gives citizens the right to use weapons in private self defence of their lives and property against illegal attack, and specifically lays down that if in the course of such defence, even innocent people happen to get killed, the persons engaged in self defence are not culpable for the deaths.

Moreover, in many places, no defence whatsoever was offered, yet gurudwaras and homes did not escape destruction. For instance, Vasan Singh of East Vinod Nagar, another trans Yamuna colony, described as follows how his neighbourhood was attacked. He said that on November 1, at about 10 a.m., truckloads of men from nearby villages were on their way to Delhi. They were shouting anti Sikh slogans. Some of them came down the highway and burnt the gurudwara which is near the main road. None of the Sikhs in the colony dared go to the defence of the gurudwara. The police was present at this time, but remained inactive. The mob next went to the house of Niranjan Singh, a postmaster. They beat up the family, burnt the house, and burnt several members of the family including children.

Vasan Singh goes on : “We went and hid in the house of a Hindu neighbour. Every Sikh ran and sought shelter in Hindu homes but very few could save their lives.”

Despite all the rumours that have been set afloat, ever since Bhindranwale’s terrorist squads shot into prominence, about the “enormous supplies” of arms that have been accumulated by the Sikh community, the facts that came to light from the accounts of the four days of violence are quite contrary to most popular prejudices. Very few Sikhs had any arms to speak of. Even the major gurudwaras in Delhi which were strongly suspected of being arsenals, had to give in to the attackers without much of a fight. There were hardly any non Sikhs among those killed.

Was violence due to anger at Khalistani terrorism? An explanation frequently offered for the massacres is that anger and resentment against the Sikhs had been brewing ever since Bhindranwale’s gang began the indiscriminate murder of Hindus in Punjab, in pursuance of their demand for Khalistan, a separate nation state for Sikhs, which might involve a forcible mass exodus of Hindus from Punjab, similar to that which took place from various areas when Pakistan came into existence.

There is no denying that the manner in which the demand for Khalistan was being pursued in the last two years or so had created a good deal of resentment against Bhindranwale among Hindus both in Punjab and outside. But the fact that one gang of terrorists who happened to be Sikhs killed some Hindus and Sikhs in Punjab is no reason for thousands of Sikhs all over India who had nothing to do with the Punjab killings to be massacred.

Bhindranwale’s men not only slaughtered Hindus but also killed Sikhs who opposed them with even greater fervour than they did Hindus. In fact, Bhindranwale began, as do most terrorist groups, by hitting out at those members of his own community who opposed him. This was done with the intention of terrorising his own community into silent submission.

Further, the sudden eruption of violence against Sikhs seems quite out of proportion to and inexplicable by the extent of anger amongst Hindus. It is noteworthy that throughout the period when Sikhs, Nirankaris and Hindus were being killed in Punjab, there had been no retaliation by Hindus against Sikhs in Delhi or in other states. Even when some sections of the Akalis organised fairly aggressive processions in Delhi, no political group or Hindu militants reacted with violence or even as much as tried to obstruct the processions and rallies. The only clashes that occurred were between Akalis, the police and the administrative machinery. There were no attacks on gurudwaras or even on the homes of prominent Sikh or Akali leaders. It is even more noteworthy that in Punjab which had nearly 38 percent Hindu population, despite a long period of targeted killings of Hindus by Khalistanis, Hindus never once retaliated by counter killings or unleashing communal riots throughout the Bhindranwale period. Hindus and Sikhs do not have a history or tradition of conflict. The two communities not only share a common past and, a common culture but even today, most Sikh families have Hindu relatives because it used to be a common practice for some Hindu parents in certain areas of Punjab to dedicate one son to the guru as a Sikh.

Even today, marriages between Sikhs and Hindus are considered socially acceptable. Many Hindus routinely visit gurudwaras and read the Granth Saheb with much devotion. The fact that all Punjabis use the word mona to indicate either a Hindu or a clean shaven Sikh shows that no rigid distinctions have been set up by the people of the two communities between themselves.

Many have tried to justify the violence by asserting that Sikhs “provoked” an attack on themselves by celebrating Indira Gandhi’s death. They are supposed to have distributed sweets at home and champagne abroad as soon as they got the news.

During these days, I have met hundreds of people who talk authoritatively about the distribution of sweets by Sikhs in celebration of Indira Gandhi’s death, but when questioned, not one of them could say that he or she saw this happen. However, the most important point we need to remember is what Dharma Kumar said in her article in the Times of India : “If all the sweets in India had been distributed -that would not have justified the burning alive of one single Sikh.”

Nevertheless, there is very little evidence that, barring a few stray cases, Sikhs in general “rejoiced” at Mrs Gandhi’s death. For instance, the reality behind the rumour that Sikh students of Khalsa college, Delhi university, danced the bhangra is a fairly typical example of how facts are distorted beyond recognition in an attempt to provide some kind of justification for the terror and killings. These students had been practising bhangra every day on their college lawn for over a month prior to Mrs Gandhi’s death. They were preparing the dance as an item for the forthcoming winter festivals that are held in every college. On October 31, they were practising as usual and stopped as soon as they got the news.

A friend tried to investigate the source of another rumour that a wealthy Sikh family in Janakpuri had distributed sweets and dry fruit soon after Mrs Gandhi’s death. They discovered that there had indeed been some distribution of sweets. This was done in honour of the coming Gurpurab. Traditionally, about 10 days before Guru Nanak’s birthday, which fell on November 8 this year, prabhat pheris are organised in each area, and it is customary for families to entertain the pheri participants with sweets and other refreshments.

Surely, it was not only Sikhs who could be accused of not cancelling a routine ritual celebration such as this one after they heard of Mrs Gandhi’s death. The night of the 31st, when I was walking down the main road in our locality, I saw a wedding procession marching along in full pomp and show, complete with band music, dancing and lights. Nobody showed any concern that this Hindu wedding procession was going through the normal ritual.

In our own neighbourhood, where at least half the families are Sikh, I saw no sign of celebration or distribution of sweets. In fact, even on the morning of the 31st, when the news of the assassination came, I was really surprised to see everyone, both Hindu and Sikh, going about their business without any apparent sign of grief or frenzy. No one I talked to cried or broke down when discussing the news even though most people felt sad that her life had ended so tragically.

Other rumour mongers point to the fact that many Sikhs did not celebrate Diwali this year because they were mourning the army operation and the killing of Bhindranwale and other Sikhs in the golden temple in June. This is cited as proof that they are “antinational” and hence it is assumed that they must have rejoiced at Mrs Gandhi’s death. First, it is not true that Sikhs who had been targeted did not celebrate Diwali. Some of the victims mentioned that new clothes and utensils bought by them for Diwali were destroyed in the attacks on their homes.

Another thing that is held against the Sikhs is that they felt outraged at the entry of the army into the Golden Temple. To say that all those who felt grieved at the desecration of the Temple were desirous of Indira Gandhi’s assassination is a bizarre falsehood. Many of those who were attacked, beaten and murdered were longstanding supporters of the Congress (I). Many men in relief camps talked about how they had worked for the Congress (I) party in previous elections. In many of the burnt down houses, I saw pictures of Indira Gandhi still hanging on the walls. Her pictures also adorn the walls of many Sikh homes in our neighbourhood, and continue to do so even after the riots.

Most important is the fact that the group of Sikhs who bore the main brunt of violence were those living in resettlement colonies. This group had almost no connection with Punjab extremist politics. or even Akali Dal In fact, many of them have no connection at all with Punjab.

The most popular of all justifications offered is that the violence was the result of mob fury at the brutal assassination of India’s foremost leader at the hands of two Sikhs.

As far as the theory of people’s frenzied outrage at Indira Gandhi’s death is concerned, one would have been compelled to take it seriously had the riots remained sporadic, unorganised and spontaneous. From the information so far available in Delhi, one is left in no doubt that the whole affair was masterminded and well organised, and that the killers and looters seemed to be pretty confident that no harm would come to them. They seemed to be in no hurry. They came, went back, came again and again. Each time, they returned with reinforcements.

Those who saw the mobs did not get the impression of a group of people angry or in anguish but of a bunch of hoodlums who seemed to be having a good time, fun and games. On November 1, I confronted one mob in Lajpat Nagar. Around noon, when we heard that the local gurudwara had been set on fire, three of us from manushi office rushed to the spot and tried to persuade the neighbours to help extinguish the fire. At once, we were surrounded by hostile men while women jeered at and abused us from a distance. At the same time, a crowd of about 200 men came, shouting slogans about revenge. Looking at them laughing, jeering, catcalling, one did not get the impression of any grief whatsoever. All one saw was a hoodlum’s delight in demonstrating his power. The jeering mob told us that if we did not keep quiet and get lost, they would throw us into the fire. All this while a couple of police men stationed there remained mute spectators.

The fact that all over the city the attacks started simultaneously and the pattern of violence was identical indicates that this was no spontaneous outburst. Victims from different parts of the city say that the first organised attacks in residential areas began between 9 and 10a.m. on November 1. Almost everywhere, the attackers came armed with lathis, a few knives and kerosene. There seem to have been few instances of the use of revolvers to kill. Almost everywhere, males were singled out and slaughtered. A fairly standard method of killing was adopted all over the city and in fact, in almost all the towns where riots took place. The victim would be stunned with lathi blows or stabbed. Kerosene or petrol or diesel would then be poured over him and he would be set on fire while he was still alive. Very few of the burn victims seem to have survived.

Congress-orchestrated cries of revenge started at AIIMS: An eyewitness account of some of the happenings outside AIIMS gives us a clue about the genesis of the murderous slogan : “Khun ka badla khun se Ienge” (We will avenge blood with blood) that was chanted by the groups of killers throughout Delhi, beginning on October 31 : “I was outside AIIMS between 1.30 and 5 p.m. on October 31. There was a large crowd gathered there but it had no resemblance to a frenzied mob. At about 2 p.m., two truck loads of men from neighbouring villages were brought to AIIMS. They dismounted from the trucks in a calm and orderly fashion. They behaved like soldiers waiting for orders.

“The trucks were followed by a tempo full of lathis and iron rods. There were no men in the tempo besides the driver. At about 3 p.m., a Congress corporator from the trans Yamuna area addressed the gathering. Later information has confirmed that he is one of those who masterminded the riots in the trans Yamuna area. He gave a fiery speech. There was a lot of drama and slogan shouting during his speech. He was the first to raise the slogan : khun ka badla khun se lenge.’ From that moment, it became a popular chant. The first victim of their wrath was a Sikh SHO from Vinay Nagar police station who came to the hospital on his motor bike. He was attacked with rods and was rescued with difficulty by senior police officers. This, in my view, was the first attack on a Sikh in Delhi, and it was instigated when the mob took their cue from the Congress leader. From the AIIMS this gang soon went in different directions-towards Naoroji Nagar, INA market, Yusuf Sarai and South Extension. They began to stop all vehicles driven by Sikhs. They beat up the Sikhs and burnt the vehicles. Some Sikhs were burnt to death. Sikh shops in these areas were looted and burnt.”

A vast number of investigative reports in newspapers and victims’ accounts have pointed out that high officials of the Congress (I) masterminded the whole operation. They rounded up antisocial elements from their constituencies. These elements routinely receive Congress (I) patronage. On this occasion, they were incited to kill, rape, loot and burn, and were assured that no one would interfere with them.

The populous resettlement colonies and the UP and Haryana villages around Delhi have been meticulously cultivated as vote banks and political bases by the Congress (I) throughout the last decade. It is from these areas that truckloads of men are routinely mobilised for Congress (I) rallies and processions. These professional processionists have become habituated to hiring out their services to the ruling party. The gang leaders are on the regular payroll of the party. That is how Congress (I) leaders could, in a matter of hours, mobilise thousands of hoodlums for the orgy of violence which they organised. Among the most active participants in the gangs were young boys, many in their early teens, who can easily be mobilised.

It is significant that reports confirm that gujjars (both hindu and Muslim), scheduled caste men and Muslims constituted the bulk of the attacking mobs. This identical pattern has been reported from areas of Delhi that are many kilometres apart. Many victims have alleged that Congress (I) men used voters’ lists and ration shop records to supply the attackers with addresses of Sikh families in each locality. So preplanned was the whole operation that the attackers not only had prior knowledge of which houses and shops belonged to Sikhs but also seem to have known which Sikh house owners had Hindu tenants and which’ Hindu house-owners had Sikh tenants. Such houses were handled differently from those inhabited by Sikhs only. Instead of the whole house being burnt, only the Sikhs were killed and their possessions looted so that the Hindus in the house were left unscathed.

Many prominent leaders have been named in several newspapers as having instigated riots. The PUCL-PUDR investigative report “Who Are The Guilty” mentions H K.L. Bhagat, Minister of State for Information and Broadcasting; Sajjan Kumar,Congress (I) MP from Monpolpuri, who is reported to have paid Rs 100 and a bottle of liquor to each man involved in the killings; Lalit Maken, Congress (I) trade union leader and metropolitan councillor, who is also alleged to have paid Rs 100 and a bottle of liquor to rioters, and who was seen actively instigating arsonists; Dharam Das Shastri, Congress (I) MP from Karol Bagh; Jagdish Tytler, Congress (I) MP; Dr.Ashok Kumar, member of the municipal corporation, Kalyanpuri; Jagdish Chandra Tokas, member of the municipal corporation; Ishwar Singh, corporator; Faiz Mohammad, Youth Congress (I) leader; Satbir Singh of the Youth Congress (I), and many others, along with the lower level local Congress (I) ruffians and hoodlums, as having led many of the mobs.

In Naroji Nagar market, an eyewitness saw the Youth Congress (I) office bearer, Pravin Sharma, stand in front of a Sikh shop and personally direct the looting operation. Young boys from the nearby hutments were invited to take whatever they wanted from the shop. This distribution continued for at least an hour. Perhaps this is the Congress (I) way of implementing their version of socialism. In fact, some Trilokpuri residents reported that they were invited to join the looting operations which were christened the “Garibi Hatao” campaign.

The way party stalwarts chose to pay tribute to Mrs Gandhi and mourn her death during those four days brought out blatantly what the ruling party has been reduced to. Many of the leaders behaved as though they were leaders of a gang rather than prominent members of a national political party. It was as though their chief gang leader had been killed and they wanted to terrorise those who they imagined constituted a threatening rival gang. Since there was really no rival gang at hand, they substituted for it all Sikhs with long hair and beards. These men, they decided, were a threat to their being considered the top gangsters, so terrorising the former would show who still had real power. A popular explanation of prominent Congressmen’s involvement that we heard was “Takat azma rahe thhey” (They were testing out and proving their strength).

Neighbourhood help and defence efforts: One of the most positive things that happened during those dark days in Delhi was the spontaneous emergence of defence and peace committees in most colonies and marketplaces. Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and other communities jointly organised to defend their neighbourhoods from attack by outsiders. In many colonies, potential trouble makers were chased away and active resistance was offered to the mobs who tried to enter the areas. Men barricaded the streets and patrolled the neighbourhoods all night.

During the days and nights when the government machinery voluntarily chose to become defunct, people organised themselves irrespective of caste or religion. These committees seem to have been more effective in areas inhabited by relatively better off and more organised communities who had more resources at their command. In the very poor areas, where people have been dumped together in appalling conditions, and the communities are not as well organised internally, people could not organise effective self defence.

In all areas, however, there were numerous instances of immediate Hindu neighbours sheltering Sikhs. For instance, Surinder Kaur of Trilokpuri described how her family was saved by a Hindu neighbour. She locked her son inside the house and came out with her daughter. The attackers threw hundreds of bricks at her house and broke everything. The neighbours came and saved them even under such risky circumstances. One neighbour stood in front of the door to prevent the house being broken open.

In most places where the residents were predominantly Hindu with a small sprinkling of Sikh houses, after the initial surprise attack on the first day, Hindus did organise to protect the Sikhs. Many families narrated how they were given shelter by neighbours who took great risks in doing so. A Hindu family I met in Shakarpur saved three families by hiding them, masking their identity and helping them to escape in rickshaws. Even in Trilokpuri, the damage to Sikh life and property was much greater where they were concentrated together, as in blocks 30 and 32, rather than where they lived interspersed with Hindu families. One of the rare cases of Muslims saving a Sikh family was that of Shan Kaur of Shahdara. She was given shelter by Muslims who escorted her and her children to a place of safety.

In another rare case of Muslims acting as saviours, Mahinder Kaur narrates how some of the Muslim neighbours from her mother’s locality came to rescue her and her brother’s family from another colony. She herself lives in Nand Nagri with her husband and three children but had gone to visit her brother at Yamuna Vihar. There were three men, two women and five children in the house on the 1st when, at about 9 a.m., a mob of about 500 came and began to stone the house. The family locked themselves in, and hid. Their neighbours, in an attempt to save them, told the mob that the house was empty since the Sikh family had escaped the previous night. The mob went ahead and burnt the nearby gurudwara as well as dozens of Sikh homes in the locality. Some of their neighbours then came to talk to them and advised them to escape since the mob had gone away for a while. They were afraid to travel along the roads while the mob was still on the rampage. But the neighbours clearly told them that they would not shelter the Sikh men. So they decided to stay hidden together in their house. At 3 a.m., however, a group of Muslim men came to their house to rescue them. These were neighbours of Mahinder Kaur’s mother who lives in Jafrabad, a trans Yamuna village which has a predominantly Muslim population. These men had brought several burkahs with them. The three Sikh men and the two boys were dressed in women’s clothes, covered with burkahs and taken to Jafrabad where they remained safely till the relief camps came into existence. Had they not been rescued at that juncture it would have meant certain death because the mob returned at 5 p.m., broke open the door and searched the house to see if anyone was hiding. They looted some of the stuff but were dissuaded by the neighbours from setting fire to the house. Mahinder Kaur says the Muslims of that locality had similarly rescued dozens of Sikh men and kept them in their houses for several days.

A Sikh family which had recently shifted to a middle class colony, Dilshad Garden, beyond the Yamuna, said that even though there were many killings, burnings and lootings all around, they were kept in a protective cocoon by their neighbours who brought them everything they needed so as to save them from having to step out of the house. When the city was facing severe shortage of milk, they had more than enough. Many Hindu families also kept in safe custody the valuables such as cars, jewellery, cash, videos and other expensive items belonging to their Sikh friends and neighbours.

However, in many cases, the neighbours were not willing to take the risk involved. In many cases, the families initially gave shelter, but as soon as the mob began to approach, the Sikhs, especially the men, were asked to leave on the plea that the sheltering family would otherwise be placed in danger. This amounted to handing over these men for murder to the mobs because once they came out, with the mob all around, there was no possibility of escape.

After attacking and killing all the Sikh men they could lay their hands on, the mob left and came back again in hordes and insisted on searching every house, including those of people of other communities, to see if any Sikhs had taken refuge there. Anyone they found hiding was slaughtered. Sometimes, they broke down the roofs of victims’ houses to ensure that people hiding inside would be crushed to death.

The fact that Hindus in large numbers did come to the rescue of Sikh neighbours was perhaps the only hopeful sign in an otherwise nightmarish situation. While many helped neighbours to hide and escape surreptitiously, Hindus could not came forward in an organised way to resist the mob fury because they were completely stunned by the mayhem and did not grasp what the mainsprings behind the pogroms. To top it all, was the fear of their own families and homes being burnt to ashes.

There is evidence that wherever even a small number of determined individuals came forward, they were able to stop even big mobs from running amok. For instance, in Yusuf Sarai market, which is only about a furlong away from AIIMS, from where the killing spread on the 31st of October, the local shopkeepers organised very brave resistance. A mob came and set fire to the gurudwara. They were about to attack Sikh shops next. The Hindu shopkeepers came and lay down in front of the shops and told the mob they would have to burn them before they burnt the shops. Not a single shop was burnt or looted in this area, then or afterwards.

Similarly, a friend went and rescued a Sikh colleague from his house in a riot affected neighbourhood in broad daylight on November 1, and brought him to his own house on his motorbike. Some of the neighbours threw stones at them but did not proceed to further violence when this failed to intimidate the rescuer. Even in a highly disturbed disturbed colony in West Delhi, my 60 year old father along with a 70 year old woman from a neighbouring house successfully prevented a mob from setting fire to a house. A couple of rioters threw petrol balls into the house but these two courageous persons mobilised help from the locality to extinguish the fire, and persuaded the mob to leave.

In rare cases, those non Sikhs who tried to come forward and remonstrate with the mob did get beaten up and harmed. But on the whole, those who stood their ground were able to save that particular situation.

Many neighbours allowed Sikh women to seek refuge but refused to shelter men. Somti Bai of Trilokpuri says she and her family hid in the house of a local Congress leader. While he kept assuring her that her three sons were safe in the house, he subsequently turned them out of the house, which was as good as handing them over to the mob, which was on the rampage all around. All three sons were killed. Somti’s sister-in-law was raped. Her two sisters were kidnapped and released only after three days had passed.

Another horrible but typical example of callous cowardliness of neighbours was reported by an eyewitness in Shankar Garden, a middle class colony newly established in West Delhi. A mob attacked a Sikh house, pulled out an old man and set his clothes on fire. He ran into the house of a neighbour who helped him get off the clothes and extinguish the fire. But the mob soon began to pelt this house with stones. The family then folded their hands before the elderly Sikh and asked him to leave by the back door because they were not ready to risk further attack. As soon as the Sikh emerged, the mob encircled him. They seemed to be in no hurry for they spent about 20 minutes collecting stones. They then formed a circle round him and began stoning him to death. At this, his young son came running out of the house to save his father, who was by then half dead. The mob immediately pounced on the son, tied his arms and legs, poured kerosene on him and burnt him to death.

This entire incident, from beginning to end, was watched by hundreds of neighbours standing in their courtyards or on roof tops, yet no one had the courage to intervene. The old man was crying for water but no one came forward even to meet this need because the attackers stood around in threatening postures.

Several such instances have been reported where determined intervention by neighbours and onlookers could have averted killings. Not only did people fail to intervene. They seem to have watched with the same mixture of dread and repulsion with which viewers watch violence on the cinema screen.

All for the glory and unity of the Nation? Unfortunately, the Congress party went overboard in convincing people that the killings and arson were, in some way, justifiable. They tried convincing people b that a purging operation was necessary in order to “save the nation” and “keep the nation united.” The ruling party made itself the arch symbol of a united nation and let loose this propaganda that “Sikhs had to be taught a lesson.” At the same time, nobody wants to face the responsibility for the horrific deeds that were done in the name of teaching this lesson. This is especially so amongst middle class people. After asserting that the Sikhs had to be given a fitting reply, people at once seek shelter behind the comforting reflection that it was “these lower caste” poor people who did the killings, conveniently forgetting that the leaders who incited the mobs are from their own class.

The complex quality of concern: Also, in middle class colonies, other factors than mere undiluted concern for neighbours seem to have been at work to get them to offer help to some of their close neighbours. In the colonies of well off people, almost none of the local residents were key participants in mob activity. Almost always, the attackers descended from outside of the colony and were perceived as belonging to the lower castes and classes, who were making use of the opportunity to loot and plunder. Some of my elite leftist friends even interpreted it as some sort of a class war.

Those middle and upper class colonies which adjoined villages and resettlement colonies seem to have been worst affected. The residents, therefore, fell prey to the fear that the selective looting of Sikh houses could spread to other houses. I heard residents of some of the affluent colonies say that the lower classes had been eyeing the growing prosperity of the rich with increasing resentment and had grabbed this occasion to acquire consumer items that they could not otherwise hope to get throughout their lives. The fear that if an adjoining house was burnt, the fire might spread or that the attackers might lose their sense of discrimination and loot non Sikh houses as well, seems to have spurred many more people into organising mutual defence.

Sadly, there are also reported cases of neighbours having helped the attacking mob to identify Sikh homes. A woman from Babarpur alleges that “a local ration shop owner brought the attackers to our house. We know him very well. We always had good relations with him. But he and his brother betrayed us. The killers were men from the interior alleys of our locality. They came around noon on the 1st. My son had been told to cut off his hair and had done so the night before. He had kept vigil all night with the other men of the neighbourhood. But the ration shop owner recognised him though his hair was cut and pointed him out, saying : ‘He is a Sardar. Kill him.’ The killers poured kerosene on him and on my husband and burnt them both to death.”

Yet it remains true that in most areas, immediate Hindu neighbours, on the whole, offered help, or at the very least, did not join the attackers. When local men joined the mob, or rejoiced with it, they were not immediate neighbours of the victims but were residents of a nearby block or street in the same locality.

Rumour as a weapon: Even while people helped their neighbours and friends, ferocious rumours were set afloat to discourage people from offering such help. In Trilokpuri, as well as in other areas, several families who had given shelter to Sikh women told me obnoxious and unbelievable stories about Sikhs who were given shelter in Hindu homes having butchered their benefactors. There was also the absurd story of a barber who cut the hair of a Sikh at the latter’s request but received sword blows on his ears and in his stomach as a parting gift. Such rumours were and are rife in every locality, from the affluent to the poverty stricken.

Unfortunately, this kind of rumourmongering goes on unabated even after the Sikhs have been subjected to such violence and terrorisation. During and after the carnage, there have been several rumours of how Sikhs have retaliated or are planning to retaliate, in and outside Punjab. The stories about water poisoning and trainloads of massacred Hindus, which ran like wild fire through the city, have been proved utterly baseless. But stories of how Sikhs are planning to reavenge themselves are still doing incalculable damage. For instance, a domestic servant in our locality told us that the army had to be called into her colony because the residents were convinced that the Hindus were in imminent danger of an attack by the Sikhs who had sought shelter in Balasaheb gurudwara nearby. It was rumoured that 9,000 Sikhs, equipped with all kinds of arms, had gathered in the gurudwara and were ready to retaliate. However, the reality was that about 1,500 people, most of them women and children, in a pitiable condition, were living in the gurudwara relief camp. The rumour also gave rise to a disgusting demand that the relief camp in the gurudwara be disbanded because Sikhs were congregated in large numbers there.

Thus these rumours have become not only a way of justifying the monstrous happenings which have no real justification, but also a weapon that is used with telling effect against the victims.

Women Excluded from Defence Efforts: All the killing, looting and burning was organised by men. In some cases, after the initial attack was over, women and children also joined in picking up whatever they could lay hands on by way of loot. At Punjabi Bagh, for instance, men, women and children from J. J. Colony, Madipur, came in swarms to claim their share of booty from the gurudwara and from some houses. But the attacking mob was exclusively composed of men.

The organised efforts at defence and peacekeeping were also confined almost exclusively to men. Women were meticulously kept out of these efforts in most areas. Men, as usual, ran the whole show by themselves. On television, when residents were interviewed, some women said the role they played was that of serving tea to the men who kept vigil all night.

In our neighbourhood, Lajpat Nagar, the first initiative to call a meeting of the residents was taken by the Residents’ Association of the block, which is not a very active body in normal times. In this association, as in all such bodies, women are never approached to become even nominal members if there are any men in the household. A widow without grown sons may be asked to pay a membership fee in her own name, but will not be expected to attend meetings or to take an active interest in the doings or non-doings of the association. Since I happen to be one of the few women who has no male “head of the household”, I was enrolled as a member in my own right.

Yet, though I approached the office bearers to find out if a meeting was being called and to ensure that I was informed so that I could attend, neither I nor any other woman was allowed to be part of the neighbourhood meetings and deliberations. Men took for granted that it was their job to defend the area. Women were expected to run inside their homes if an attack occurred.

Women in our locality and in most other areas of the city, acted merely as carriers of rumours that their sons, husbands and brothers brought in from outside. None of the men thought it necessary to involve women in the effort at self defence nor were there any instances of women taking the initiative to organise their own meetings to discuss what they should do in case of an emergency. At the same time, in many Sikh households, because of the danger to men’s lives, most of the outside chores had to be performed by women. Within most homes, of course, women did participate in discussions as to what the family should do if something went wrong. But this was not allowed to happen at the community level.

Women were, however, active in relief work. Students and teachers of women’s colleges in Delhi have been particularly active in organising relief teams.

The role of government machinery: In one sense, this was not an unusual period. The entire government machinery seems to have lived up to its usual motto : “Do not move or do anything until there is a push and a kick from above.If you do something you are more likely to annoy someone in power than if you do not do anything.”

This is summed up very aptly by N.K. Saxena, a senior police officer quoted in the November 25 issue of Express Magazine : “I have no doubt that a good few police officers make dangerous compromises because, according to their calculations, the risk of their dismissal for failure is not more than one percent, while their being disgraced for doing their duty seriously is over 50 percent.”

A striking example of this safe nondoing was the way All India Radio handled the news of Mrs Gandhi’s death. They were the last to announce her death, and kept playing their routine jazz and film music hours after BBC and several other foreign radio stations had announced the news and had started broadcasting condolence messages from different world leaders. It was a typical display of mindless servility and slavish self censorship, characteristic of the government owned media in India.

While the city burned, many senior politicians, bureaucrats and police officers seem to have spent most of their time dancing attendance at Teen Murti house where Mrs Gandhi’s body lay, or preparing to receive foreign dignitaries for the grand funeral. Others were busy helping to coordinate the murder, rape and plunder.

Shameful role of police: Almost everywhere in the city, the police too seem to have performed a well rehearsed role. Either they were absent from the scene and failed to make their appearance despite repeated appeals from affected and concerned citizens or, if they were present, they behaved at best like amused spectators. In many cases, they actively abetted the criminal acts, and in some cases, even participated in them.

A friend who witnessed the burning of Yusuf Sarai gurudwara described the role of the police: “Between 3 and 4 p.m., on November 1, a local hoodlum came to the policeman on duty and said : ‘Please go away from here, we want to burn the gurudwara.’ The policeman good humouredly replied : Wait for a while till I go off duty. Then you can burn it. In fact, you should burn it.’ He assured him that between his going off duty and the next man’s coming to replace him, there would be an interval of at least 15 minutes, in which the job could be done. However, the ‘leader’ was not convinced and said: ‘Look, we have the men now. We can’t wait. Besides, we know you. Who knows who the next fellow maybe?’ So saying, he put his arm around the policeman and walked him down the road for a few hundred yards, during which time the rest of the miscreants set ‘ the gurudwara ablaze.”

The PUCL-PUDR report describes similar experiences : “On November 1, when we toured the Lajpat Nagar area, we found the police conspicuous by their absence, while Sikh shops were being set on fire and looted. Young people armed with swords, dappers, spears, steel trishuls and iron rods were ruling the roads. The only sign of police presence was a police jeep, which obstructed a peace procession brought out by a few concerned citizens. When the procession was on its way to the Lajpat Nagar main market, a police inspector from the van stopped the procession and warned it not to proceed, reminding its members that the city was under curfew and Section 144. When leaders of the procession wanted to know why the arsonists and rioters were not heing dispersed if curfew was on, he gave no reply and warned instead that the processionists could go to Lajpat Nagar market at their own risk.”

Even in our own locality, after the gurudwara was set on fire, the policemen looked on with amusement as though it were a tamasha and did nothing to stop the hoodlums. When we tried to persuade local residents that we should try to put out the fire, the policemen accused us of creating a “disturbance” and tried to push us away. Elsewhere, too, the same story is told.

Even for those who wish to believe that there were no explicit orders to this effect from high up police bosses, the role that the policemen at the lower levels played would still need to be explained. The least one would have to say is that since the policemen knew that several Congress (I) men were fomenting the riots, they did not want to take the responsibility of stopping it lest they incur the wrath of their senior officers and the ruling party bosses. Hence they may have decided to adopt a safer course and do nothing obstructive.

However, since traditionally there is a close link up between the politician cum ruffian and the local police, even if there were no explicit orders from above to this effect, the two are likely to have acted in unison. And since there was promise of loot and plunder, the arsonists found ready allies among the police.Several people have alleged that a substantial portion of the looted property was cornered by policemen.