This was first published in the print edition of Manushi Journal, Issue no. 142 of 2004.

Kunti and Draupadi are two women who shape the entire course of dynastic destiny in the Mahabharata. Kunti chooses the scion of Hastinapura, Pandu, to wed, and becomes the mother of the epic’s protagonists: the Pandavas. By birth, she is a Yadava and her brother’s son is Krishna, one of the major shapers of epic action. Draupadi, arriving virtually out of nowhere as the adopted daughter of Drupada, king of Panchala and rival of Hastinapura, becomes the common wife of the Pandavas and the cause celebre of the epic.

In the Mahabharata, Draupadi and Kunti are not only closely related to each other as daughter-in-law and mother-in-law, but are also parallels. Kunti, or Pritha, is the daughter of Shoora of the Vrishnis, given away when just a child to her father’s childless friend Kuntibhoja. This rankles deep within her; she voices her resentment pointedly both before and after the Kurukshetra war (V.90.62-64). Growing up in Kuntibhoja’s apartments, she finds no mother; Kuntibhoja himself hands her over, in adolescence, to the vagaries of the eccentric, irascible and fiery sage Durvasa. Should she displease the sage, she is warned, it will dishonour her guardian’s clan as well as her own.

In the Mahabharata, Draupadi and Kunti are not only closely related to each other as daughter-in-law and mother-in-law, but are also parallels. Kunti, or Pritha, is the daughter of Shoora of the Vrishnis, given away when just a child to her father’s childless friend Kuntibhoja. This rankles deep within her; she voices her resentment pointedly both before and after the Kurukshetra war (V.90.62-64). Growing up in Kuntibhoja’s apartments, she finds no mother; Kuntibhoja himself hands her over, in adolescence, to the vagaries of the eccentric, irascible and fiery sage Durvasa. Should she displease the sage, she is warned, it will dishonour her guardian’s clan as well as her own.

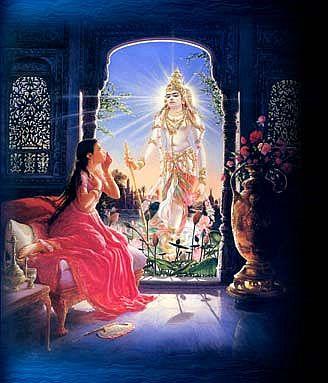

Large-eyed and well-endowed, as her name Pritha connotes, she is strikingly lovely, and Kuntibhoja exhorts her not to neglect any service out of pride in her beauty. Kunti’s relationship with Durvasa does not appear to have been easy. In the account she gives much later to Vyasa, she tells him that despite Durvasa’s conduct having been such as to provide abundant cause for anger, she had not given way to it (XV.30). She further states that she was constrained at the sage’s insistence to accept his boon, whereby any god would be compelled to answer her summons, and that she obeyed out of fear of his curse. The interaction that she describes after this between her and the sun god, Surya, is exactly similar – the same insistence and the same fear.

Kunti, like Ahalya with Indra, is curious. She wishes to test whether Durvasa’s boon really works. Significantly, this desire arises in her after she has menstruated. In her account to Vyasa, she frankly states that she had desired (sprihayanti) Surya, again reminding us of Ahalya when approached by Indra. Perceiving a radiant being in the rising sun she invites him, using the mantra. Once summoned, Surya, like Indra, will not return unsatisfied. He cajoles and browbeats the girl, assuring her of unimpaired virginity, and threatening to consume the kingdom and the boon-bestowing sage if denied. A thrilling conflation of desire and fear overpower Kunti’s reluctance, and she stipulates that the son thus born must be like his father. Kshirodeprasad Bidyabinode struck home in his Bengali play Nara Narayana (1926), with his succinct, yet profound, description of this encounter placed on Karna’s lips:

A maiden’s misstep, a god’s prurient curiosity,

A virgin’s curiosity and his shameless lust.

(IV. 3, my translation)

Kunti abandoning her first child Karna Kunti abandoning her first child Karna |

Kunti wins two boons from the encounter: her own virgo intacta and special powers for her son. In this she is remarkably akin to her grandmother-in-law, Satyavati the Queen-Mother; to Madhavi, daughter of the lunar dynast Yayati (to whose lineage she belongs); and to the Yadava Bhanumati who, too, has Durvasa’s boon that, if raped, she will regain her virgin status1. Just as Satyavati’s illegitimate son Vyasa protects the Pandavas, it is Kunti’s illegitimate son Karna who becomes the mainstay of the sons of Dhritarashtra and, like Vyasa, also repeatedly challenges the authority of the family head, Bhishma.

Little is written about Satyavati in the Mahabharata although she transformed the fortunes of the royal lineage of Hastinapura despite her low-caste origins. She obviously engaged the imagination of later redactors in the Harivamsa and even more so in Devi Bhagavata Purana (II.2.1-36). In her previous birth, Satyavati is named Achchhoda, daughter of the pitris (manes), cursed to be reborn of apsara-turned-fish Adrika, who swallowed king Uparichara Vasu’s semen.2 She resembles an early queen of the lunar dynasty, the illegitimate ashramite Shakuntala, daughter of apsara Menaka and king-turned sage Vishvamitra, who insisted, before giving in to Dushyanta’s importunate advances, that the offspring of their union alone would inherit the throne of Hastinapura.

We meet Satyavati in the epic and in Pauranic accounts as an adolescent fisher-girl called Kali, because of her dark complexion, plying her boat across the black Kalindi (Yamuna) with a lone passenger, the sage Parashara, who presses her to satisfy his desires. Finding him importunate and, pragmatically concerned that he might upset the boat in midstream, she gives in to him on two conditions: that her virginity shall remain unimpaired and that the disgusting body-odour that attends her be removed. Thus, Kali the Matsyagandha (she who stinks of fish) transforms into Yojanagandha-Gandhakali (she whose fragrance can be smelled across a yojana) who later will captivate Shantanu, king of Hastinapura. When Parashara grasps her right hand, Kali smiles, ever so much in control, ever so mature, and says (my translation):

“What you are about to do, befits it your ancestry, your ascesis or the scriptures? Your family name is spotless; of Vashishtha’s clan are you. Hence, O dharma-knower, what is this you crave, enslaved by desire? Best of Brahmins! Rare is human birth on earth. Specially rare in men is Brahmin birth. Best of the twice-born! You are highborn, virtuous, scripture-versed, dharma-knowing. O Indra among Brahmins, my body stinks of fish, yet why do un-Aryan feelings arise in you? O twice-born! Your wisdom is doubtless most prescient, but what auspicious marks do you perceive in my body that you crave me thus? Does desire so possess you that your own dharma you forget?”

So saying, she muses:

“Oh! mad to possess me this dvija has lost his senses. He’ll upset the boat and drown. He’s desperate, his heart’s pierced by desire’s five arrows; He’s unstoppable.”

Then the girl tells the sage:

“Great one, be patient till we reach the other bank.” Suta said Parashara heeded her well-meant advice. Her hand he left and sat quiet. But reaching the other side, the sage, desire-tormented, seized Matsyagandha again for intercourse. Quivering, annoyed, she spoke to the sage before her: “O best of sages! My body stinks. Can’t you sense it? Making love ought to delight both equally.” As she spoke, in a flash she turned fragrant-for-a-yojana, Yojanagandha, lovely, beautiful. Making his beloved musk-fragrant, enchanting, the sage, desire-tormented, seized her right hand. Then auspicious Satyavati told the sage bent on coitus, “From the bank, all people and my father can see us. It is daylight. Such beastly conduct doesn’t please me. It disgusts me. Hence, O best of sages, wait till nightfall. Coitus is prescribed for men only at night, not in the daytime. In daylight it’s grievous sin; if seen, brings great disrepute. Grant this desire of mine, wise one.” Finding her words proper, the generous sage at once shrouded all in the mist by his powers. As the mist arose deep darkness shrouded the bank. Then the desirable woman spoke to the sage in dulcet tones: “I’m a virgin, O tiger among twice-born. Enjoying me, you’ll depart where you will. But infallible is your seed, O Brahmin. What of me? If today I’m pregnant, what shall I tell my father? When enjoying me, you leave, what shall I do? Tell me!” Parashara said, “Beloved, today having delighted me, you shall again be virgin. Yet, woman, if you fear, ask what boon you will.” Satyavati said, “Best of twice-born, ever you honour others. Act that neither my father nor anyone knows anything. Act that my virgin status isn’t ruined. May your son be like you, wondrously gifted. May my body be forever fragrant; May my youth be forever fresh, ever new.”

Assuring Kali of her son’s fame as an arranger of the Vedas and author of the Puranas, Parashara swoops upon the consenting maiden. Having sated himself, the sage bathes in the dark waters of Yamuna and leaves, never to have any contact with her again.

This fisher-girl’s striking character emerges from this interaction. Though she has but just reached puberty, a sage, howsoever famous, does not overawe her. Instead, she reads him quite a lesson in propriety, resisting his advances with remarkable presence of mind. Noticing his violent passion, she takes care not to refuse him outright, lest in forcing her he should capsize the boat. She buys time till they have crossed, hoping his passion will have cooled by then. Reaching near the other shore, she voices her irritation and disgust at his animal lust and draws attention to her own repulsive body-odour more than once. With maturity and frankness that astonishes us even in the twenty-first century, she points out that coitus ought to be mutually enjoyable. Even after becoming musk-fragrant, she does not give in, objecting to beastly coupling in daylight in public. Once again, the sage bows to the logic of her arguments and raises a screen of mist.

Yet Kali still does not give in and raises the ultimate objection: what will her status be when he has deflowered her and departed? No one will point a finger at the high caste sage, but what about her? With a maturity that is astounding for an uneducated pubescent girl, she harbours no illusions that the sage might wed her. Hence, she obtains assurances of regaining her virgin status and of the fame of her illegitimate offspring. Only after these practical aspects have been taken care of does she allow the eternal feminine to come forward, desiring to remain forever young, forever fragrant – a gift that was Helen’s, and one that women of all times, everywhere, have craved. The Mahabharata version provides a fascinating glimpse into the feminine psyche:

And she, ecstatic with her boon, Conceived the same day From her intercourse with Parashara. 3

Matsyagandha is careful to tell the sage that, being ruled by her father, she is not at liberty to respond to Parashara’s demand. When she then breaks away from this, to assert her independence of action, she achieves that “one-in-her selfness”4 that is unique to the virgin. After intercourse, she does not become dependent on Parashara, by clinging to him or insisting that the moment be made eternity through formalised marriage. The purpose of the encounter fulfilled, both break off without any lingering backward glances or mushy sentimentality. No romantic hope is expressed of meeting again, no guilt, not even any anguished query about the child to be born. Modern-day women could well wish that they were half as confident, clear-headed and assertive of their desires and goals as Satyavati.

Satyavati goes on to take Hastinapura, and its king Shantanu, by storm. When a love-struck Shantanu asks her to marry him, she once again displays her characteristic far-sightedness by insisting that she will agree to the wedding only if her progeny succeed to the throne. Thus she manoeuvres the crown prince Bhishma out of the reckoning. When fate plays her false and both her sons die childless, she first asks Bhishma to do his duty as stepbrother and sire sons on the widows by levirate (niyoga). Because of his vow of celibacy – ironically the fruit of her own stipulation that her children must not have any rival claimants to the throne – he refuses. Now she ensures that it is her blood that will run through the ruling line of Hastinapura by forcing her princely son Vichitravirya’s widows to be impregnated by the son of her union with Parashara, the illegitimate, mixed-caste Vyasa. As the stepbrother of Vichitravirya, he has the social sanction to beget children on the widowed princesses. The offspring, Dhritarashtra and Pandu carry no part of the lunar dynasty’s blood in them. With her low-caste birth, Satyavati does not suffer from high-caste hesitations in bringing her illegitimate son into the limelight. Rather, she makes him the decisive factor in the fortunes of Hastinapura, rivalling the shadowy authority of Bhishma, who is instead ruled by her. Her disregard of social opprobrium stands out all the more when we find that her royal granddaughter-in-law Kunti does not dare emulate her in acknowledging her illegitimate son Karna. Satyavati turns the renowned Chandravamsha, the lunar dynasty, into the lineage of a dasa maiden and brings about a fascinating reversal in pauranic history.

Satyavati goes on to take Hastinapura, and its king Shantanu, by storm. When a love-struck Shantanu asks her to marry him, she once again displays her characteristic far-sightedness by insisting that she will agree to the wedding only if her progeny succeed to the throne. Thus she manoeuvres the crown prince Bhishma out of the reckoning. When fate plays her false and both her sons die childless, she first asks Bhishma to do his duty as stepbrother and sire sons on the widows by levirate (niyoga). Because of his vow of celibacy – ironically the fruit of her own stipulation that her children must not have any rival claimants to the throne – he refuses. Now she ensures that it is her blood that will run through the ruling line of Hastinapura by forcing her princely son Vichitravirya’s widows to be impregnated by the son of her union with Parashara, the illegitimate, mixed-caste Vyasa. As the stepbrother of Vichitravirya, he has the social sanction to beget children on the widowed princesses. The offspring, Dhritarashtra and Pandu carry no part of the lunar dynasty’s blood in them. With her low-caste birth, Satyavati does not suffer from high-caste hesitations in bringing her illegitimate son into the limelight. Rather, she makes him the decisive factor in the fortunes of Hastinapura, rivalling the shadowy authority of Bhishma, who is instead ruled by her. Her disregard of social opprobrium stands out all the more when we find that her royal granddaughter-in-law Kunti does not dare emulate her in acknowledging her illegitimate son Karna. Satyavati turns the renowned Chandravamsha, the lunar dynasty, into the lineage of a dasa maiden and brings about a fascinating reversal in pauranic history.

The epic and the Puranas say that the world’s first monarch was Vena, who was slain by the Brahmins because he refused to obey their dictates. Seeking a successor, they churned his right thigh and produced a short, dark, snub-nosed human whom they named Nishada. However, finding his appearance not kingly enough, they assigned him the forest as his dwelling.5 It is this nishada tribe, deprived of its birthright, whose fortunes are restored by Satyavati. Long before Mahapadma Nanda established what is known as the first shudra dynasty in the country, Satyavati daseya (of the dasas, as Bhishma calls her6 ) accomplished it in Hastinapura. She pays special attention to Vidura, born of Vyasa and her daughter-in-law Ambika’s low-caste maid, ensuring that he is brought up with the two princes Dhritarashtra and Pandu as their brother to become the undisputed conscience of the throne. Ambika’s sister and co-wife Ambalika’s son Pandu, unable to father children, has his wives Kunti and Madri beget sons for him employing the same means – levirate (niyoga) – by which he was born of Vyasa. Vidura and his father Vyasa become the protectors of the niyoga-born Pandavas against the conspiracies of their uncle, Dhritarashtra, born to their aunt Ambika by Vyasa.

The Devi Bhagavata Purana records a very important detail absent in the Mahabharata. In VI.24.15 Vyasa laments that his mother abandoned him immediately after his birth; his survival he attributes to chance. In this, Kunti parallels Satyavati, each abandoning her pre-marital first-born to fate. Grievously upset by the death of his son Shuka, Vyasa returns to his birthplace in search of his mother, finds out from the fishermen that she is now queen and, wishing to be near her, settles on the banks of the Sarasvati. Delighted to hear of the births of his stepbrothers, he refuses to beget sons on the widows of her royal son Vichitravirya, as they are like his daughters, and intercourse with the wives of others is a grievous sin. Niyoga was permissible for a widow only at the instance of the husband (as in Kunti’s case, ordered by Pandu), not of the mother-in-law. Vyasa even tells his mother that preserving the dynasty by adopting such heinous means is improper (VI.24.46-48). Satyavati once again displays her mastery of realpolitik. “Hungry for grandsons”, desperate to propagate her lineage to keep the throne secure (her grandson Pandu inherits this trait, craving son after son), she argues that even the improper directives of elders ought to be obeyed and that such compliance attracts no blame, particularly when it will remove the sorrow of a grieving mother. When Bhishma urges Vyasa to obey his mother he gives in and engages in what he describes as “this disgusting task” (VI.24.56). Vyasa wonders whether progeny born of perversity (vyabhicharodbhava) can ever be a source of happiness (VI.25.28). How prophetic! Dhritarashtra, born from Vyasa’s encounter with Ambika, who shut her eyes in revulsion, is himself blind; Pandu, born from Ambalika, who turned pale with shock on seeing Vyasa, is sickly and unable to have children.

Parashara and Shantanu were not Satyavati’s only conquests. There was yet another, which shows what a ravishing beauty she must have been. In the Harivamsa,7 Bhishma tells Yudhishthira that, during the period of mourning after Shantanu’s death, he received a demand from the usurper of Panchala, Ugrayudha Paurava, to hand over Gandhakali in return for considerable wealth. The ministers did not allow the affronted Bhishma to attack Ugrayudha, invincible because of his dazzling discus, and tried to put him off peacefully. When this failed, at the end of the mourning period Bhishma killed Ugrayudha whose discus had, in the meantime, lost its power because of his lusting after another’s wife. This incident explains Satyavati’s desperation for heirs; she was compelled to be all too conscious of the greedy eyes of neighbours on the empty throne of Hastinapura. In relentlessly pursuing her ends, she reminds us of the earliest queens of the lunar dynasty: the Brahmin Devayani and the Asura Sharmishtha. The one virtually forces king Yayati into an inter-caste marriage, while the other seduces him into fathering her sons in secret, slipping a move past her co-wife Devayani, just as, generations later, Madri betters Kunti. In both cases the younger wife charms her husband into giving her what she craves, successfully out-manoeuvring the elder.

Endnotes:

1 Harivamsa, Vishnu Parva 90.76-77.

2 Harivamsa 18.26-45.

3 Adi Parva, 63.83, P. Lal: The Mahabharata verse-by-verse transcreation, Writers’ Workshop, Calcutta, 1968 ff. All translations are from this version unless otherwise specified. References to the Sanskrit text are to the Aryashastra (Calcutta) edition.

4 M. Esther Harding: Woman’s Mysteries, Rider, 1971, London, p. 103.

5 Vishnu Purana I.13, Mahabharata Shanti Parva 59.94

6 She is of the dasa race. Harivamsa 18.45 narrates Achchhoda being cursed to be born as Daseya Satyavati. Bhishma explains in the Anushasana Parva 48.21 that offspring of a Nishada and a Sairandhri (an orphan working as a servant maid) of Magadha are called madguru or dasa, and their profession is plying ferries, which is precisely what Gandhakali was engaged in.

7 Harivamsa Parva XX.50-73