This was first published in the print edition of Manushi journal, Issue no. 153 of 2006.

Perhaps the most neglected character in the Ramayana is Urmila. Valmiki’s text mentions her only once, in two lines, to tell us that she was married to Lakshmana. We don’t hear of her again. Neither does she have a role in any of the Sanskrit tellings of the Ramayana by poets such as Kalidasa, Bhavabhuti and a number of others that follow all the way up to the nineteenth century.

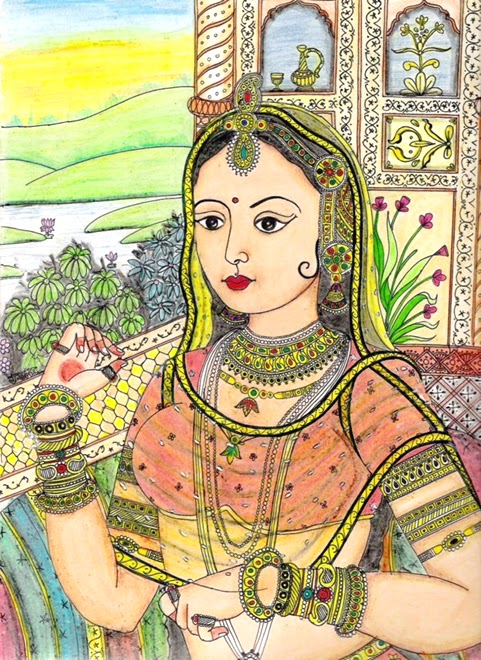

Two Telugu women’s Ramayana songs make Urmila prominent in the narrative, particularly the one usually titled Urmiladevi Nidra, (Urmila’s Sleep). Poets of this Ramayana invent an ingenious event: when Lakshmana follows Rama and Sita to the forest, Urmila wants to go with them, too. But there is a problem. Family conventions do not allow a sister-in-law to walk in the company of her elder brother-in-law. Lakshmana, therefore, has to advise Urmila to stay home, but they make a pact to exchange their sleeping and waking hours. They decided that Urmila would sleep all fourteen years, thus avoiding the pain of separation from her husband, while Lakshmana would remain awake during that whole time, all the better for him to serve his brother day and night.

Two Telugu women’s Ramayana songs make Urmila prominent in the narrative, particularly the one usually titled Urmiladevi Nidra, (Urmila’s Sleep). Poets of this Ramayana invent an ingenious event: when Lakshmana follows Rama and Sita to the forest, Urmila wants to go with them, too. But there is a problem. Family conventions do not allow a sister-in-law to walk in the company of her elder brother-in-law. Lakshmana, therefore, has to advise Urmila to stay home, but they make a pact to exchange their sleeping and waking hours. They decided that Urmila would sleep all fourteen years, thus avoiding the pain of separation from her husband, while Lakshmana would remain awake during that whole time, all the better for him to serve his brother day and night.

The central theme of the song is how Lakshmana is reunited with Urmila. In the following pages, I will present a close reading of the song.

As is usual with the women’s songs on the Ramayana, this one begins with a description of the glory of Rama. The first six lines of the song describe how, at the end of the period of exile, Rama returns triumphantly to his capital and holds court in glory. Everything is in order. Then Sita reminds Rama that his brother should go and visit his wife who has been sleeping ever since they had gone to the forest. Lakshmana dutifully obeys this order from Rama, leaves the court and goes to where Urmila is sleeping. This is where the song begins to deepen. As is ordinarily the case in an upper caste household, the front of the house is where men rule; we move in this poem gradually into the interior of the house where women control the space.

Urmila senses even in her sleep that a man has entered her room and begins to admonish the stranger of the consequences of entering her bedroom. The gradual progression of her words to the intruding man are carefully organized, poignantly describing the helpless position of a woman in a society where rape is not recognized as a crime, where the victim is blamed for the offense, and where fathers, brothers and husbands cannot be counted on for help.

“If my father Janaka hears of this, he will punish you, count on it. If king Rama hears of this, your life will be in severe danger. If my sister’s brother-in-law hears of this, he will not let you live. Because he went after another man’s wife, Indra has an ugly body. Because he went after another man’s wife, Ravana was killed and his kingdom was lost. You know these well-known stories, and still you are intent on this. Don’t you have a sister like me, and aren’t you born of a mother?”

She begins with respectful words, addressing him as ‘sir’, and tries to put on a show of strength, calling on the key men in her life and their power. The order in which they are invoked is in itself interesting in that it follows the order of their status in the family. First, King Janaka (she would have called on her father-in-law Dasaratha if he were alive), then Rama, and then her husband. It is very significant that she refers to her husband not directly, but in a round about way – “my older sister’s younger brother-in-law.” However, in my translation I preferred a less round about form, “my sister’s brother-in-law.” Of course, her husband Lakshmana is Sita’s younger brother-in-law. In upper caste families, women do not refer to their husbands directly, and even at a time of grave danger Urmila follows propriety. She knows very well that neither Rama nor Lakshmana are at hand to save her, and as far as she knows they are still in the forest. There is no way a sleeping Urmila could have known the recent events in the palace. Apparently nobody has cared to wake her up and give her the good news of her husband’s return. They have practically left her to her fate. What follows is spoken in a mood of helplessness and despair.

“My great family’s name is tarnished now, helpless me, what can I do? The famous family of my birth is blemished, helpless me, what can I do?”

It is a familiar story: the family is scandalized when a woman is raped. The victim does not even have the freedom to suffer for herself; she has to bear the guilt of bringing both her families – the one into which is married, and the one in which she is born – into disrepute.

Urmila takes a different tack, that of intimidating the attacker by reminding him of the horrible fate men who have desired other people’s wives have suffered. She first mentions the story of Indra. He desired sage Gautama’s wife Ahalya, and went to bed with her by taking on the appearance of her husband. The sage catches him redhanded, and curses him to wear a thousand vaginas on his body. Then comes, very interestingly, the story of Ravana who kidnapped Sita in the forest and in the end lost his kingdom and his life in a battle with Rama. One would, of course, wonder how Urmila could have known of these events? She is fast asleep when these events are taking place in the forest, right? This serious discrepancy does not seem to bother the poet. It is a good story, and a powerful weapon in the hands of a woman who seeks to ward off a rapist, too good to be left out for silly reasons of linear chronology. Then follow the usual pleas for sympathy. Doesn’t the rapist have a mother, and a sister? Would he wish that they suffer a similar tragedy?

Let us remember that Urmila is still sleeping. Even in her sleep, she knows that she is vulnerable, an existential condition of women in general in this society. One would imagine that all her words were so well rehearsed in her subconscious that she can reel them off, even in her sleep. Now comes an even deeper layer of her subconscious. Lakshmana tries to tell her that he is her husband. But note closely, he never uses the word ‘husband’; this culture does not allow him to do so. He finds a circuitous route to identify himself, just like his wife does when she referred to him earlier in the song. He is Rama’s brother, Sita’s brother-in-law, Janaka’s son-in-law, and so on. What is totally mind-boggling is how Urmila responds. A devoted wife and a properly behaved daughter-in-law of a noble family, she totally trashes every family relationship. She has never heard of Rama, and does not know who on earth Janaka (her father) is, nor does she know Sita.

How can one interpret this bizarre conversation? Let’s remind ourselves again that Urmila is talking in her sleep. Is this the real Urmila, who is free from the burdens of life as a wife, as well as the shackles of family, a woman free to speak for herself? Has she harbored deep resentment against all those who have kept her under the rules of proper family behaviour as a good daughter-in-law, deprived her of freedom and joy and made her utterly helpless? She is the lowest on the totem pole; her father has abandoned her, giving her in marriage to a young man who had no backbone to stand up for his or his wife’s interests. The big man Rama did not even care to know if she exists or not. Sita, her senior in the hierarchy of palace women, who has negotiated and won her own freedom to follow her husband to the forest, did not give a second thought to Urmila, her own sister. She could have advised Rama not to stop Urmila from following her husband to the forest. Clearly, everyone in the family has left her for dead. Urmila is painfully aware of the cruel politics of a family that pretends that all is well. She has every reason to be resentful against them. It is only under the veil of deep sleep, however, that she is able to give expression to her repressed anger, which she would never be able to do when she is awake and obligated to behave properly. It is common knowledge in India that women give vent to their anger against the senior and respected members of the family in states of hysteria, when they are possessed, or when they are otherwise sick. This altered state gives them the alibi of a different persona, which allows them the perfect mask to speak their mind.

Lakshmana tries shock treatment: he breaks the news that Sita was kidnapped in the forest and that they had to fight a battle with Ravana to bring her back. The strategy does not work, and Urmila does not move. Lakshmana makes a pathetic appeal: You are the woman I married, and if you don’t accept me, I lose my good name in the world. Totally counterfactual, this statement attracts our notice. It is common knowledge that women who are left by their husbands get a bad name in this culture, but never the other way around. Apparently, women want a world in which men get a bad name (apa-kirti) as well when the wives reject them; they have represented their wish in this song. But let us hear Lakshmana some more.

Lakshmana again proclaims his identity as Sita’s younger brother-in-law, and urges her kindly to wake up from sleep. This is a message that he has understood her anger and that he does not mind the words spoken in sleep, and he does not hold them against her.

Lakshmana keeps on talking to his wife to convince her of his love. He says he cannot live any longer if she does not accept him; he has not eaten or slept since he left her, (which is true) – the kind of words women would love to hear from their husbands.

Finally when a crying Lakshmana takes his sword and is ready to kill himself, Urmila startles awake, recognizes Lakshmana – and falls on his feet, like a proper wife is expected to do. He picks her up and wipes her tears. Urmila still voices her grievance, this time politely, like a proper wife, but in an accusing tone all the same:

“My father was naive in giving me to you,” she said. “He didn’t know the truth. He thought you were a proud man and was blissfully happy for you. But in fact, you have your mind elsewhere, you belittle your own wife.”

A strong indictment indeed. Lakshmana is accused of being a weak husband, incapable of protecting his honour, and furthermore, he does not even love his wife. He cares more for his elder brother and his wife, and does not have any qualms about humiliating his own wife.

Lakshmana understands the gravity of Urmila’s feelings, and feels sincerely sad for her. He reiterates his love for his wife and repeats the things he has said to her while she was still sleeping. He wants to make sure she hears him while she is fully awake. He swears he did not sleep or eat and stayed alive all these fourteen years only for her. He resorts to the concept of fate to explain what had happened; they must have caused the separation of some innocent couple in a previous life, and they have paid for it now in this life. The result of past karma is inescapable, and anyway, he is not the only one to blame.

The rest of the song is all a happy story of family reunion, a delightful picture of harmony, fun and joy – things women love to belong to. Urmila for once is the centre of attention, the heroine of the day. She and her husband are bathed and dine in a celestially beautiful dining room, as the sisters-in-law lovingly tease her. The family humour of women, particularly familiar for Telugu families, adds a gentle touch of love and affection to the song. Sita (and we can imagine Mandavi and Srutakirti as silent partners, even though they are not mentioned in the text) takes Urmila’s side and Shanta is on the opposite side as joking parties are formed.

Shanta is a relatively unknown character in Valmiki’s text, but as Rama’s sister, she has a fully developed role in women’s Ramayanas. A husband’s sister, called adapaducu in Telugu kinship terms, has a role that could smoothen the transition of a bride from her parent’s family to the parent’s in-law’s family. As a woman she can be closer to the bride than her own husband, and almost always belongs to the same age group as the bride. She can also be a mild authority figure since she is closer to the husband; she is his sister who grew up in the same family as he did while the new bride is from a different family. A Telugu proverb says that a sister-in-law is half a husband, (adapaducu artha mogdu). She is potentially capable of making or breaking the relationship of the bride and her husband. The new bride fears her more than her husband and worries if she is on her right side or not. She dreams of a sweet sister-in-law as much as she fantasizes about a loving husband, because a difficult sister-in-law can cause real hell for her while a friendly sister-in-law can be a source of great comfort. In this context, an affectionate and friendly role for Santa in the women’s songs is easy to imagine.

Also, in the joint family culture, a wife never accepts that she has attracted her husband by her beauty, and often rejects being described as attractive. If we follow the course of the banter, we see that the first remark Shanta makes is about Urmila’s beauty. It is so seductive that jealous people may cast an evil eye on her. Shanta proposes an offering to cast off the evil eye and protect Urmila’s beauty.1 Sita quickly, but politely (vinayamuto), retorts that the honour should belong to Rama and his brothers who make the whole world fall in love with them. They are ruling kings, they are handsome like Indra, the king of gods, and Chandra, the moon – the most handsome among gods. The ritual of casting off the evil eye should done for them. But Shanta is not done yet. Haven’t the four sisters – Sita, Urmila, Mandavi and Srtakirti – cast a spell of beauty on her four brothers? Sita again has a quick response. Santa is no less skilled at the game of love. She has charmed a virgin sage Rishyasringa, living in the forest, innocent of a woman’s touch. (It may be recalled that Rishyasringa, a unicorn figure in the Ramayana, grew up in the forest knowing only his father and has never seen a woman.) Note that Sita refers to Rishyasringa as her brother. That is how it works in the Telugu kinship chart of an extended family: a sister-in-law’s husband is a brother.

Now comes the bedroom scene. The description is again very familiar to a Telugu listener and a staple in older Telugu movies. The soft and inviting bed, the bedside items of fragrances, aphrodisiacs, and mild narcotics such as betel leaves and areca nuts. A fan made of vattivellu, (dried fibrous roots of a plant, which emit a pleasant fragrance when they are sprinkled with water) is put in place for the couple to fan each other. The doors are closed and the couple is alone with each other. The song moves on to describe some of the most delicate moments of the couple’s love life. The wind brings the fragrance of champak flowers and jasmine. The couple is sitting on the bed. Lakshmana loosens Urmila’s long hair tied into a bun, and skillfully braids it. He decorates the braids with jasmine and jaji flowers, something he is very good at. A very gentle touch indeed, and perhaps one of the rare fantasies of women who seldom have their husbands doing such womanly things for them. As they sit chewing betel, Urmila asks about Sita’s capture by Ravana. Apparently she did hear Lakshmana when he broke the news to her while she was sleeping.

Now she wants to know the complete story, a blow by blow report of the events as they happened. The most important thing she wants to know is how it was possible for Sita to be taken away when Lakshmana, who is a warrior like a lion, was present. Right at this moment the poet informs us that Kaushalya, Sumitra, Kaika and Shanta – all the senior members of the family – are seated on raised seats, very quietly. They are listening in, keeping an eye on the goings on in the bedroom. So much for the privacy of a new couple in joint family households. But, unaware of the spying elders, Urmila continues her line of questioning, repeatedly asking how, when such great warriors like Lakshmana and Rama were there to guard her, Sita was taken away by the demon Ravana.

What follows is a short retelling of the central story of the Ramayana, one from Lakshmana’s point of view. The nuances of what is included and what is left out make the retelling very significant and make you want to listen to it, even though it is a story everyone knows. The narrative begins with a rationalization that it was all fated to happen the way it happened. No one is to blame, except Time, the ultimate maker of events. Lakshmana gently reiterates the point that he entreated “mother Sita” not to ask him to go when the magic deer cried out Sita’s and Lakshmana’s names. (A subtle touch here is that Sita’s name is also included. The standard Ramayanas tell us that Maricha, who came in the form a magic deer, cried out only Lakshmana’s name.) Just as gently he includes the point that Sita said words sharp as arrows, without going into the details. He relates that he had drawn a line around Sita and commanded that no one should cross it, and that Ravana took Sita away breaking the very earth on which she stood. (This is what the southern Ramayanas tell as opposed to Valmiki’s version which describes Ravana taking Sita away by lifting her up with his hands under her buttocks.) Lakshmana takes care to tell that he recognized only the anklets among Sita’s jewels. (A detail that deserves our attention here is that Sugriva gave the jewels to Rama as a gift “because he was Kaushalaya’s son,” a touch we attribute to the woman poet who composed this song.)

What follows is a short retelling of the central story of the Ramayana, one from Lakshmana’s point of view. The nuances of what is included and what is left out make the retelling very significant and make you want to listen to it, even though it is a story everyone knows. The narrative begins with a rationalization that it was all fated to happen the way it happened. No one is to blame, except Time, the ultimate maker of events. Lakshmana gently reiterates the point that he entreated “mother Sita” not to ask him to go when the magic deer cried out Sita’s and Lakshmana’s names. (A subtle touch here is that Sita’s name is also included. The standard Ramayanas tell us that Maricha, who came in the form a magic deer, cried out only Lakshmana’s name.) Just as gently he includes the point that Sita said words sharp as arrows, without going into the details. He relates that he had drawn a line around Sita and commanded that no one should cross it, and that Ravana took Sita away breaking the very earth on which she stood. (This is what the southern Ramayanas tell as opposed to Valmiki’s version which describes Ravana taking Sita away by lifting her up with his hands under her buttocks.) Lakshmana takes care to tell that he recognized only the anklets among Sita’s jewels. (A detail that deserves our attention here is that Sugriva gave the jewels to Rama as a gift “because he was Kaushalaya’s son,” a touch we attribute to the woman poet who composed this song.)

Implying that as a good brother-in-law he has only looked down at her feet, not upon the rest of her body. And then it was he who made the fire for Sita to enter. He rejoiced that the fire was cool like a lake to the supremely chaste. Sita was pure and therefore came back to Rama. And then the poet tells us that Lakshmana told Urmila “all the troubles he had suffered in the forest.” As we come to the end of the song, we move out of the bedroom, into the women’s circle of Urmila’s sisters. They talk among themselves about what Rama did to Sita: “Now you have heard what kind of a mind our Man with the Wheel has.” But the word used, “buddhulu,” is a gentle reproach. They know that’s where they have to stop. No severe protests, only a general weary resignation: “What’s the point in worrying about the past.” They are happy now, Rama is on the throne.

The title the singers give to the song is, “Urmila’s Agony in Separation.” And the text says at the end that Lakshmana bestows the world of Vishnu on whoever sings or listens to this song. This is a song of Urmila and Lakshmana, but more significantly, this is song about women, about how they feel and think. The sensibilities, the interiority of the characters, the representation of a subconscious and the attention given to the neglected “subaltern” characters of the mainstream Ramanyanas makes the song very much a modern song. It makes you wonder if modernity in India began only in the late nineteenth – early twentieth century, as is commonly claimed, or much earlier, in the late fifteenth century, as I and my collaborators David Shulman and Sanjay Subrahmnayam have been arguing for some time.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The author is Professor, Department of Languages & Cultures of Asia, University of Wisconsin, USA