This was first published in the print edition of Manushi journal, Issue no. 134 of 2003.

Ever since I was a little girl, I have heard in bits and pieces mythological stories surrounding the goddess Kali Ma. My mother is a Kali devoteed. She has graceful, as well as grotesque images of the goddess in her home shrine. She also visits a neighbourhood Kali temple. Once a year, my mother hosts a day-long, religious discourse given by her longtime teacher, Guru Maharajji, who often lectures on Kali and other Hindu goddesses.

My early memories of the goddess Kali are those of wonder combined with curiosity. Her gruesome appearance and dreadful paraphernalia have kept me at bay. Kali did not pull me toward her, as did other goddesses. I wondered why a goddess would look so fearful. When I was much older, I put this question to my mother. In answer, my mother narrated Kali’s sacred stories to me, telling me about the destruction of Chanda and Munda; her drinking of Raktabija’s blood and of her dreadful defeat of him; her slaying of the demonking, Nisumbha, and of the demoness, Daruka. My mother also discussed Kali’s frantic dances after the killings. Gruesome killings? Frantic dances? Although the myths were engrossing, they did not make any sense to me at the time.

My early memories of the goddess Kali are those of wonder combined with curiosity. Her gruesome appearance and dreadful paraphernalia have kept me at bay. Kali did not pull me toward her, as did other goddesses. I wondered why a goddess would look so fearful. When I was much older, I put this question to my mother. In answer, my mother narrated Kali’s sacred stories to me, telling me about the destruction of Chanda and Munda; her drinking of Raktabija’s blood and of her dreadful defeat of him; her slaying of the demonking, Nisumbha, and of the demoness, Daruka. My mother also discussed Kali’s frantic dances after the killings. Gruesome killings? Frantic dances? Although the myths were engrossing, they did not make any sense to me at the time.

Whenever I confronted a Kali image, I carefully studied it to see which myth was being represented. Some of her images did not resemble a myth, and they were unattached to any sacred stories I had heard. I started listening to Guru Maharaj ji’s discourses about Kali with exceptional attention. I had envisioned, read about, and listened to Kali’s deeds for years. The goddess had touched me at some deeper level of understanding, the extent of which I could not comprehend.

I was intrigued at the puzzle: Why did Kali keep on emerging from the bodies of auspicious deities — from Durga, Shiva, and Sita? I realised that she was their personified rage, but what did that mean to a devotee? And why did she dance a frantic dance of death after destroying demons?

One winter, Guru Maharaj ji spend a day giving a discourse about the Great Goddess Devi and her manifestations. The segment about the goddess Kali was stimulating to me. The following day after breakfast, he was sitting quietly on a wooden chair looking relaxed in his saffron-coloured, cotton dhoti, loose shirt, and a shawl. I sat cross-legged on the ground next to him, and he blessed me by putting his hand on my head. He asked me how I was doing at my college. “Fine,” I replied, looking up at him. I asked, “What is the meaning of all this dreadful imagery in the myths of the goddess Kali?”

“Child, it is not easy to experience spiritual matters when we try to understand them,” he emphasised the word ‘understand’ and continued. “Understanding is good, but, eventually, it is only through feelings and experience that we understand them.”

Kali’s Essence: “How do you ‘feel’ a goddess?” I asked. “When you have devoted yourself to the worship, adoration, and meditation of a deity for years, one day you get yoked to her essence. You don’t even know — suddenly, you feel her power residing within you,” said Guru Maharajji, while continuously turning his rosary behind the cotton shawl wrapped around his shoulders.

“What is Kali’s essence?” I asked.

“Her essence is her power. Her myths and images represent her power feebly. It is not until you feel her presence that you know what she is. Her essence is her.”

“Such holy occurrences cannot be put into words, child. But, as I have said before, if you begin to worship, adore, and focus on a deity of your choice — in your case, I would think it is Kali — you should be able to feel her. After venerating her for a few years, thus, focusing on her Yantra may accelerate your spiritual progress.” He picked up his jhola- from the floor and pulled out a colourful, geometric diagram from it.

Pointing to the diagram he said, “This is Kali’s Yantra. The Yantra is considered to guide a devotee’s enlightenment. By focusing on this geometric form, you can be led to a state in which you will experience her invisible power. It not only contains Kali’s immense cosmic power, but it also symbolises the inherent forces within your mind as the goddess’ devotee. Her potent imagery is condensed in her yantra as her inherent energy.”

Pointing toward the centre of the yantra, Guru Maharaj ji continued. “What I am going to explain is symbolic. It represents the cosmos in a geometric diagram. Kali, in union with her male partner, Shiva, forms the central dot, or bindu, as the source or womb of the world. Here, she is the cosmic movement and he is her foundation. Without her movement, the whole of existence is inert, like a corpse. The fifteen corners of the five concentric, inverted triangles represent the psychological states: the five senses, their receptive functions, and the five organs of action. The circle of the Yantra represents samsara, the cycle of life, and Maya, the great delusion. As Maya, she leads one to believe that the fleeting and shifting appearances of the world is its Reality. Thus, the circle of the Kali Yantra indicates that the veil of Maya, which confines an individual to the circle of life, needs to be disclosed in order for her to see Reality as it is. The eight lotus petals of the Yantra denote the earth elements of prakriti—earth, water, fire, air, ether, mind (manas), intellect (buddhi), and ego sense (ahamkara). The Kali Yantra can also be seen as a psychological arrangement. The gates drawn outside the lotus petals represent the doorways to your own unconscious mind. Once you have been able to focus on your mind, you will be able to penetrate through the eight lotus petals, and that will indicate your envelopment with the spiritual essence. When you cross over the circle and the triangles, you will understand the meaning of delusion, which is created by samsaric cycles, and you will be able to comprehend the psychological states. Those will become the stages of your spiritual ascent. Finally, when you reach the bindu, you will make a link with the goddess Kali and, at the same time, with your innermost self.”

Guru Maharaj ji gave me the Yantra. I thanked him for his gift and looked at it for a few moments. I had understood all the separate words he spoke, but their meaning, as a whole, eluded me. I started performing Kali puja each morning. Over the next twenty years, while I graduated, got married, and had children, I enshrined Kali’s images and her Yantra in my home shrine, as had my mother. I focused my mind on her image, read her myths, and listened to discourses about her. In short, I became a genuine Kali devotee, and her imagery kept me intrigued.

A Devotee’s Encounter: Over and over again, I have looked at the images of the goddess Kali. I have been meditating on her yantra. I have been listening to discourses about her and reading about her legends and myths. I have become aware of the seven spiritual wheels of energy in my body. It seems to me that goddess is gradually disclosing herself to me.

A Devotee’s Encounter: Over and over again, I have looked at the images of the goddess Kali. I have been meditating on her yantra. I have been listening to discourses about her and reading about her legends and myths. I have become aware of the seven spiritual wheels of energy in my body. It seems to me that goddess is gradually disclosing herself to me.

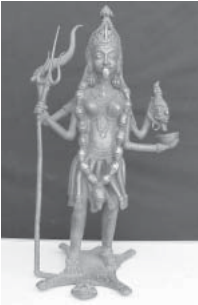

In my early twenties, when I inquired about Kali’s presence from Guru Maharajji for the first time, I was a spiritual infant. After more than two decades of continuous adoration and dedication to the goddess Kali, I have started to feel her presence. I was in the stages of ‘between and betwixt.’ Recently, I have been feeling that the goddess has picked me up and is caressing me. I believe I need to understand her essence more keenly before I can feel the intensity of her potent power. I understand that her three eyes represent the powers of the sun, moon, and fire. Her dishevelled hair suggests her uncontrollable nature. Her lolling tongue expresses her defiant attitude. Typically, her four arms represent samsara, the cycle of birth, death, sacrifice, and release. In some images, she brandishes a sword (khadga), which expresses the destruction of ignorance. At times, she holds a severed and bloodied head (munda), depicting the dawning of insight. The hand in the gesture ‘fear not’ (abhaya) suggests one who is unafraid, and, lastly, the gesture of ‘boon-giving’ (varada) offers the beholder a doorway to spiritual transformation.

Kali’s nude and unadorned images and her audacious behaviour mock at the passivity of the individual: a demure daughter; a suffering, yet yielding, wife; a timid woman; or those faint-hearted members of the society who do not fight for their rights and freedom. Through her imagery, Kali stimulates submissive women and men to move beyond the status quo of social norms. The fragility of the human body is conveyed through the depiction of dismembered bodies. These sinister accessories scoff at those who do not see the fragility and impermanence of life.

I understand that Kali’s dance symbolizes aggressive movement. Unless an individual activates his/her mind through movement, no change is possible. An individual’s dance of freedom in uncontrollable frenzy is a must in a society in which the behaviour of women, as well as members of the economic lower classes and castes, are set in regimented patterns. Such a social structure needs to be radically changed.

Kali’s frantic dance is the fire of devotion, burning away the devotee’s limitations, ego, fear, and ignorance. Her dance is the blazing fire in the devotee’s heart. At the time when the devotee realises the impermanence and fragility of life, the veil of his/her delusion is removed. The devotee ‘dies’ to his/her previous ignorant self and is reborn as a spiritual infant. Kali’s dance is, therefore, a process of becoming: a personal transformation toward spiritual emancipation.

In the saptamatrika goddess cluster, the infant seated on Brahmani’s lap represents the initiate or a devotee who is spiritually only a newborn. While Brahmani signifies the lowest chakra, Maheshvari, Kaumari, Vaisnavi, Varahi, and the five middle chakras (personified energy centres) signify the five rungs of the ladder toward liberation, which the devotee must ascend. As the spiritual infant passes from one matrika to the next, she progresses along the road to emancipation. Kali represents the uppermost chakra and completes the initiate’s ascent.

Sati jumped in the glowing fire so that she could renew herself. She immolated herself symbolically and slew her demons, in this casxhe imagery of the myth of Sati, the idea that it is only through the human body that spiritual transformation is possible is powerfully conveyed. I understand the connection between infants, battlefields, and cremation grounds. They are symbols of the spaces or thresholds that function as doorways from life to death or from death to life, where spiritual transformation is possible.

I understand that the emotion of outrage, when channelled as Kali, may express itself as physical prowess, a dance of freedom, the cleansing of demons, and the outpouring of activity. Kali’s symbolic imagery, her ferocious mien, grotesque appearance, her bloody weapons, and her gruesome behaviour has aroused my inherent strength. Viewing her images with intensity has helped me to get in touch with deep creative centers within me.11

My heart has been cleansed by the fire of my total dedication to Kali. The goddess has killed the dreadful demons of my mind. She dances frantically within my heart. Now, I have triumphed over my fears of death and life. I feel Kali’s presence.

The energy unleashed by Kali has ignited the power of my heart. It reminds me that I must live my life with determination and boldness; that I must question familial and social norms that have remained unquestioned; that if I am exploited in any situation whatsoever, I must dance frantically until I achieve my freedom; that I must be constantly aware that life is fleeting; and that death is not something to be afraid of and must be confronted.

In conclusion, Kali’s presence reminds me that opposites are linked together, and that although the world may seem fragmented into malevolent and beneficent, creative and destructive, or male and female, in reality, it is a unified totality. Human beings must accept the terrible, as well as the sublime. To feel both is to be fully human. It is not the melding or the mingling of the two aspects that brings enlightenment, rather the discovery that one is unsanctioned and meaningless without the other.

From Kali’s Divine Mouth: I am Kali. I am blackness, death, and time. I am naked, bloody, and dark, and I dance in an uncontrollable frenzy. My dark skin is sometimes youthful and at other times wrinkled. My hair is always unbound, if not dishevelled. I am usually shown with my third eye, and all three eyes are bloodshot and sunken. I have hollow cheeks, a gaping mouth, lolling tongue, and large fangs. At times, blood trickles from the corners of my mouth. I have a sunken belly and sagging breasts. I gesture with each of my four hands or hold symbolic emblems in them. In my upper-left hand, I hold a cup made from half of a human skull, filled with blood. In my lower-left hand, I hold a severed head. My upper-right hand wields a sword, while my lower-right hand is in the gesture abhaya (fear not). Sometimes, one of my hands makes the gesture varada mudra (boon-giving) or bindu mudra (the flicking of drops of blood or wine). From my neck hangs a garland of fifty human heads. Human hands dangle from my waistband.

I am devoid of opulent ornaments. Almost all of the other Hindu goddesses are heavily embellished with them; draperies, floating scarves, girdles, necklaces, armlets, anklets, and garlands encircle their limbs, while head-dresses and halos crown their heads. All of those ornaments signal their auspicious holiness. My divinity however, is concealed in the audacity of my dark and naked body. My sinister accessories symbolize my divine power. Some of images of me are grotesque, while others are benevolent. I kill demons on battlefields, and then I dance the dance of freedom. At times, I dance in cremation grounds. At other times, I stand on my husband’s supine body, surrounded by corpses, jackals, snakes, and ghosts. I have been known to wear infants as ear-ornaments. On other occasions, I embrace and suckle a newborn on a battleground.

I am as popular as is any other mainstream Hindu goddess, such as Lakshmi, Sarasvati, Parvati, Durga, Sita, or Radha. The images of these goddesses are alluring and auspicious, while mine are grotesque and dreadful. Yet, throughout India I am highly regarded, especially in the cosmopolitan cities where people from different groups live. Recently, I have attracted worldwide attention.

In order to portray the meaning of my visible essence, Indian artists have developed a visual language that shows my ferocious mien, grotesque appearance, bloody weapons, and gruesome behaviour. The function of this symbolic language is to reveal fundamental truths about human life. It is a commentary on some of the deepest truths about the actions of peoples and individuals. Even when represented in a pictorial form, these truths are not immediately evident to the casual observer, and the meaning of my energies remains hidden from them. My image does not disclose its true meaning at the surface; rather, my power is only revealed to those sensitive observers who look long and hard at my images, who have a deeper level of understanding, and who seek my inner reality.

My rather complex mythic and symbolic imagery can be categorised into three simple headings, so that a sensitive observer is able to understand and to feel my energy and power: Blood, Bones, and Body Parts; Devastation, Death, and Dissolution; and Spiritual Emancipation.

Blood, Bones, Body Parts: My symbols are of a different sort than those of the auspicious Hindu goddesses. Whereas theirs include lotus flowers, musical instruments, weapons, and other material emblems, mine consists of blood, body parts, bodily fluids, bones, carnivorous birds, and animals. I exude raw power. I drink the blood of demons on the battleground and stand amidst severed bodies.

At times, I can be seen in the cremation grounds, while the flesh of dead bodies is flaming on the pyres, and while jackals and carrion birds chew human bones. My pedestal (pitha) is often a dead body (pretasana or savasana), my garland is made of human heads (mundamala), and my skirt is fashioned out of human hands. In my hair or in my hand, I don a grinning human head (munda). Some representations depict me in various stages of life: as a beautiful young woman; a wrinkled hag (Kankali); or a fleshless skeleton goddess. My images depict me in various stages of women’s lives: as a virgin; a sexual partner; a mother; a matron; and an old woman. Gradual, physical transformation through the life cycle is an integral part of my imagery.

Death and Devastation: I am the personification of divine wrath or venom. I emerge from divine bodies, and I fight, kill, and defeat dreaded demons like no other warrior. I, however, remain untouched by my enemies, participating in the bloodshed but remaining above it. Having completed my gruesome killings, I dance in frenzy, and when I dance, I am wild and uncontrollable. I dance on battlefields and cremation grounds. The depiction of devastation and death are central to my images. I am the personification of divine wrath. I wreak havoc and destruction on battlefields.

Tales About Me: In an episode of the Devi Mahatmya, the goddess Durga confronted Chanda and Munda, who were assistants of the demon kings, Sumbha and Nisumbha. The god Brahma had granted the assistants a boon, the protection that they could never be slain by any man (a woman was considered too weak to fear). Upon confronting them, Durga’s face became dark with rage. At that moment, I sprang from her brow, I, Kali of the terrible countenance. I appeared emaciated, with sunken eyes, drooping breasts, a skeletal body, and four arms. I was wearing a long garland of severed heads, as well as a serpent necklace around my neck. Another snake, which was coming out of and entering my navel, was tied around my hip. My deformed breasts heightened my grotesque and frightful image. The sunken cavities of my body sharply contrasted with those of the graceful Durga.

I cut off the heads of the demons Chanda and Munda and presented them to the goddess Durga, since earning the title of Chamunda. I then returned into Durga. Later, in a battle, Durga summoned me once again to help defeat the demon Raktabija (whose blood is semen), an ally of Sumbha and Nisumbha. This demon had the ability to reproduce himself instantly whenever a drop of his blood fell to the ground. Durga had seven female Saptamatrikas (seven companions mothers) helping her, and I was one of the seven. Durga had already wounded the demon Raktabija, and the drops of his blood that were falling onto the earth were forming additional, duplicate images of him. This time, Durga’s anger knew no bounds. Once again I emerged from her as Chamunda, the personification of her rage. I assisted her by sucking all the blood from each demon’s body before any of it could touch the ground. With my gigantic tongue outstretched, I drew the countless duplicates into my mouth and devoured them.1

Finally, the most dreadful of demonkings, Sumbha and Nisumbha, came to the battlefield with an army of their envoys. As Saptamatrikas, we were assisting the warrior goddess Durga. I was the most ferocious of the seven. Together, we fought on the gruesome battlefield. As Nisumbha went forth to fight Durga, she beheaded him. When Sumbha went before Durga, he was overcome by her beauty, delicacy, alluring charm, and prowess. It was at that moment that I attacked Sumbha and slew him. After the slaughter of Sumbha and Nisumbha, I danced a hysterical dance of triumph, and it was impossible to control me. Once again, Shiva came to calm me down. He pleased me by dancing the tandava dance and I started dancing with him.

On another occasion, I arose as the goddess Sita’s fierce anger. Her husband, Rama, was confronted with the thousand-headed demon, Ravana. As Rama and his army attacked the demon, Ravana shot arrows that drove Rama’s allies back to their homes. Alone on the battlefield, Rama began to weep. Rama’s condition made Sita angry, and through her divine power, she summoned me as her personified rage. I attacked and killed Ravana.

I got into a frenzy after destroying Ravana. I started drinking his blood and throwing his body parts all over. Then I commenced an earth-shattering dance, from which no one could stop me. When the gods implored Shiva to intervene and calm me down, he came to the battlefield on which I was dancing madly. He threw himself down among the corpses of Ravana’s slain soldiers. I started dancing with Shiva under my feet. It was only when Brahma directed my attention to the body beneath my feet that I recognised it to be that of my husband, Lord Shiva. I was astonished and embarrassed and stopped my dance. At once, I was consumed back into Sita. She resumed her appearance as Sita and accompanied her defeated and humiliated husband to their home.

One time, Shiva asked his wife, Parvati, to destroy the demoness Daruka, who could be killed only by a female. Parvati entered Shiva’s body, and from the poison in his throat, she transformed herself into me, and I reappeared.

I was murderous in appearance. I attacked and killed Daruka and his army with the help of my assistants. After the killings, I danced in a frenzy and brought havoc to the world. My fury shook the universe. Shiva came back, not as himself but as an infant, in order to drink away my anger. He lay on the battlefield, as a newborn, amidst the dead demons. When my motherly love heard the cries of an infant lying among the corpses, I picked him up, kissed him, and nursed him. Thus, I became calm. Glad to see me composed, Shiva transformed into himself again and began to dance. I was delighted, and I joined him in his dance along with my assistants.

On a metaphysical level, I personify primordial chaos. My stark, black colour presents me as the cosmic annihilator and as the primordial void before the new cosmic creation begins. Just as all the colours of spectrum are consumed into black I, Kali, the Black One, withdraw everything into my cosmic body.

I am one of the Saptamatrikas (Seven Mothers). In Vedic texts, we originated as the inner power (shakti) of the gods. Our names were derived by using female suffixes at the end of the names of the gods: Brahmani from Brahma; Mahesvari from Mahesvara; Kaumari from Kumar (or Krittakeyi from Krittakeya); Vaisnavi from Vishnu; Varahi from Varaha; Indrani from Indra; and Kali from Kala. Together, we have assisted the great gods in their battles against the dreadful demons. In Puranic myths, we are the battlefield goddesses: militant, ferocious, and blood-drinking deities.

Yet, in sculptural portrayals, all the other six are depicted as royalty, benevolent, and compassionate. My image, however, continues to thrive as terrifying and gruesome. My image is a perfect terrifying balance to the other six benevolent Shaktis. As Saptamatrikas, we are often depicted in the company of infants, whom we carry on our hips or hold by the hand. Our images integrate aristocratic elegance and maternal love. Seated in the lap of Brahmani, the first ‘mother,’ is an infant. While Brahmani signifies the lowest chakra (the energy centers within the body of a yogini or a yogi), Maheshvari, Kaumari, Vaisnavi, Varahi, and Indrani signify the middle chakras. I represent the uppermost chakra and complete the internal passage toward spiritual ascent. Although I am often represented as terrifying and gruesome, when I am in the midst of this group, my essence ceases to be the bloodthirsty warrior goddess who kills and dances frantically.

Another cluster of goddesses with which I am associated is known as the Dasamahavidyas, the Ten Great Wisdoms. We are Kali, Tara, Chinnamasta, Bhuvaneshvari, Bagala, Dhumavati, Kamala, Matangi, Sodasi, and Bhairavi. Our origin is described in the Devibhagavata Purana. Daksha, the chief priest, had a daughter named Sati who married the god Shiva against her father’s wishes. Daksha disliked Shiva, the god of wilderness and a dweller in the cremation grounds. Therefore, when Daksha held the great sacrifice to which all the inhabitants of heaven were invited, he invited neither Sati nor her husband. When Sati found out about it, she became angry and felt disgraced. Although uninvited, she wished to attend the sacrifice. Shiva prevented her from doing so.

At Shiva’s refusal to let her go, Sati became furious. Her limbs trembled and her colour changed to red. Shiva closed his eyes, and when he opened them a female stood before him. She was terrible in appearance: dark and frightening, with dishevelled hair. She had four arms, her limbs were smeared with sweat, and her tongue was lolling. She was completely naked, except for a garland of severed heads around her neck, and a half moon, which she wore as a crown. She shone like a million suns, which filled the world. She had a deafening laugh. It was I, Kali. Shiva tried to flee, but it was to no avail. I surrounded him with my ten different forms, collectively known as the Dasa Mahavidyas. I then re-entered Sati’s body.

Sati stormed off to her father’s abode and threw herself into her father’s great sacrificial pit, vowing to be born again only to a father she could respect. Upon hearing the news of his wife’s immolation, Shiva became enraged. He arrived at Daksha’s home and cut off his head. He picked up his wife’s charred body and carried it around until it broke into pieces, falling one by one onto the earth.

Ever since later Puranic times, the cremation ground has become my dwelling place, and I have become dissociated with battlefields. I am the quintessential ‘death’ of an ego-andignorance-laden life. I destroy demons of fear, delusion, and ego. I lead the initiates toward spiritual emancipation. I am also the power of wisdom that arouses the initiate from the illusion of existence. I am the embodiment of knowledge that wakens the mind toward spiritual awareness.

I am who I am. My visual imagery helps my genuine devotees to understand my power and essence. When I started dwelling in the cremation grounds, I was associated with the dreadful (Bhairava) form of Shiva. Eventually, I was also coupled with his auspicious form, (Shiva). Now I am a supreme Hindu goddess. I am the Dark Mother — Kali Mata.

Readings

- Rachel Fell McDermott, “The Western Kali” in Devi: Goddesses of India, Eds. John Stratton Hawley and Donna Marie Wulff, University of California Press, California, 1996.

- Jeffrey Kripal, “Kali’s Tongue and Ramakrishna: Biting the Tongue of the Tantric Tradition,” History of Religions 34, no.2, November, 1994.

- David R. Kinsley, Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahavidyas, University of California Press, 1997 and The Sword and the Flute: Kali and Krsna, Dark Visions of the Terrible and the Sublime in Hindu Mythology, University of California Press, 1975.

- Kinsley’s “Tara, Chinnamasta and the Mahavidyas”, pp.161-177 in Hindu Goddesses.

- Katherine A. Harper, “Seven Hindu Goddesses of Spiritual Transformation: The Iconography of the Saptamatrikas,” Studies in Women and Religion Vol. 28, The Edwin Mellen Press, 1989.

- Katherine H. Lorenzana, “Early Hindu, Tantric Art”, 1989 (unpublished paper).

- Rita M. Gross “Hindu Female Deities as a Resource for the Contemporary Rediscovery of the Goddess”, in The Book of the Goddess, Past and Present: An Introduction to Hindu Religion, Ed. Carl Olson, Crossroad, New York. 1983. “

https://withoutprescription.guru/# ed meds online without doctor prescription

mexican rx online: mexico drug stores pharmacies – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

can i purchase amoxicillin online: order amoxicillin uk – amoxicillin for sale online

https://canadapharm.top/# canada pharmacy reviews

mexican mail order pharmacies: mexican drugstore online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

how cЙ‘n i get cheap propecia pills: cost of cheap propecia pill – order propecia pills

https://canadapharm.top/# canadian pharmacies

viagra without a doctor prescription: real cialis without a doctor’s prescription – best non prescription ed pills

india online pharmacy: world pharmacy india – world pharmacy india

https://levitra.icu/# Generic Levitra 20mg

tadalafil over the counter uk buy tadalafil europe tadalafil for sale in canada

https://tadalafil.trade/# tadalafil online without prescription

erectile dysfunction medicines: best ed medication – cure ed

Vardenafil online prescription Levitra 20 mg for sale Levitra online pharmacy

п»їkamagra: super kamagra – cheap kamagra

https://levitra.icu/# buy Levitra over the counter

п»їkamagra: Kamagra 100mg price – sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra

Levitra 10 mg buy online Buy Levitra 20mg online Levitra 10 mg best price

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but

your sites really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your site to

come back later on. All the best

https://tadalafil.trade/# best tadalafil generic

https://levitra.icu/# Vardenafil buy online

ed drugs list erectile dysfunction medications new ed drugs

Kamagra 100mg: Kamagra Oral Jelly – buy kamagra online usa

https://sildenafil.win/# sildenafil from mexico

https://azithromycin.bar/# how to get zithromax online

order amoxicillin online no prescription: amoxicillin 875 125 mg tab – buy amoxicillin canada

amoxicillin capsule 500mg price: amoxicillin 250 mg capsule – generic amoxicillin

purchase zithromax online buy cheap generic zithromax can you buy zithromax over the counter in canada

https://lisinopril.auction/# cheap lisinopril 40 mg

buy generic zithromax no prescription: zithromax z-pak – buy cheap generic zithromax

amoxicillin for sale online purchase amoxicillin online generic amoxicillin cost

https://amoxicillin.best/# amoxil generic

buying amoxicillin online: purchase amoxicillin online – amoxicillin buy online canada

lisinopril 2.5 mg price Over the counter lisinopril lisinopril 419

doxycycline tablets over the counter: Doxycycline 100mg buy online – order doxycycline without prescription

zithromax 500 mg lowest price drugstore online: zithromax antibiotic – zithromax capsules australia

how to get amoxicillin amoxil for sale amoxicillin for sale online

doxycycline 200 mg price in india: Doxycycline 100mg buy online – where to get doxycycline

https://amoxicillin.best/# buy amoxicillin canada

cipro ciprofloxacin Get cheapest Ciprofloxacin online buy generic ciprofloxacin

https://azithromycin.bar/# zithromax over the counter canada

zithromax 1000 mg online: buy cheap generic zithromax – buy zithromax 1000 mg online

zestril 10: buy lisinopril – zestril 40 mg

https://ordermedicationonline.pro/# canadian drugstore viagra

mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs best online pharmacy pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa

canadian pharmacy: canada drugs online review – global pharmacy canada

legal canadian pharmacy online: safe online pharmacy – buy prescription drugs from canada cheap

https://ordermedicationonline.pro/# perscription drugs without prescription

india pharmacy: top 10 online pharmacy in india – top online pharmacy india

price drugs: online pharmacy no prescription – canadian pharmacy rx

https://buydrugsonline.top/# canada medicine

mail order pharmacy india: best online pharmacy india – india online pharmacy

canadian pharmacy tampa: trust canadian pharmacy – drugs from canada

https://clomid.club/# order generic clomid pill

paxlovid generic: cheap paxlovid online – paxlovid covid

https://clomid.club/# can you get clomid online

ventolin without a prescription: ventolin 500 mg – ventolin hfa 90 mcg inhaler

https://gabapentin.life/# neurontin mexico

wellbutrin 100 mg: buy wellbutrin – buy cheap wellbutrin

paxlovid buy https://paxlovid.club/# buy paxlovid online

https://wellbutrin.rest/# cost of wellbutrin generic 75mg

2018 wellbutrin: generic for wellbutrin – order wellbutrin

https://claritin.icu/# how much is ventolin in canada

Paxlovid over the counter: Buy Paxlovid privately – paxlovid price

https://gabapentin.life/# neurontin 100 mg

paxlovid covid: Paxlovid without a doctor – Paxlovid buy online

https://paxlovid.club/# п»їpaxlovid

farmacia senza ricetta recensioni sildenafil prezzo dove acquistare viagra in modo sicuro

viagra prezzo farmacia 2023: viagra online spedizione gratuita – viagra prezzo farmacia 2023

https://farmaciait.pro/# farmacia online senza ricetta

farmacie online affidabili: Tadalafil generico – farmaci senza ricetta elenco

farmacia online migliore: avanafil generico prezzo – farmacia online

farmacie online affidabili: avanafil generico prezzo – farmacia online migliore

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: Tadalafil prezzo – acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

farmacia online migliore: kamagra gel – farmacia online migliore

https://kamagrait.club/# farmacie online sicure

farmacia online migliore: cialis prezzo – acquisto farmaci con ricetta

migliori farmacie online 2023: avanafil generico – farmacia online migliore

migliori farmacie online 2023: avanafil spedra – farmacie online autorizzate elenco

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: comprare avanafil senza ricetta – farmacia online migliore

п»їfarmacia online migliore farmacia online miglior prezzo п»їfarmacia online migliore