This was first published in the print edition of Manushi journal, Issue no. 145 of 2004.

In the earlier instalments we have, first, considered the three kanyas of the Ramayana—Ahalya, Tara and Mandodari—followed, in the second instalment, by Satyavati who shares many features that distinguish her grand daughter-in-law Kunti whose remarkable character and deeds were examined in the third part. In the last issue we looked at Kunti’s daughter-in-law, Draupadi. In this concluding piece we seek to find answers to the question with which we began: why are these five women termed ‘Kanyas’ “(virgins)” and what is the secret of their being celebrated as having redemptive qualities.

A common feature shared by all the five panchkanyas is “motherlessness.” The births of Ahalya, Tara, Mandodari and Draupadi are unnatural; none have a mother. Satyavati is born of an apsara Adrika who is turned into a fish by a curse. In emerging from the elements, Tara, Ahalya, Mandodari and Draupadi resemble the ocean-born apsaras. We know nothing of Pritha-Kunti’s mother. Motherless Gandhakali-Satyavati and Pritha are given away by their fathers Uparichara Vasu and Shura in childhood. Kunti finds no fostermother and her only succour is an old midwife. MatsyagandhaSatyavati does not even have that. As adolescents, both are left by their foster-fathers, the Dasa chief and Kuntibhoja, to the mercies of two eccentric sages and become unwed mothers with no option but to discard their first-borns.

If Draupadi had hoped to find her missing mother in her mother-in-law, she is tragically deceived, as Kunti thrusts her into a polyandrous marriage that exposes her to salacious gossip reaching a horrendous climax in Karna declaring her a whore whose being clothed or naked is immaterial. As if that were not enough, Kunti urges her to take special care of her fifth husband, Sahadeva, as a mother! No other woman has had to face this peculiar predicament of dealing with five husbands now as spouse, then as elder or younger brother-in-law (to be treated like a father or as a son respectively) in an endless cycle.

If Draupadi had hoped to find her missing mother in her mother-in-law, she is tragically deceived, as Kunti thrusts her into a polyandrous marriage that exposes her to salacious gossip reaching a horrendous climax in Karna declaring her a whore whose being clothed or naked is immaterial. As if that were not enough, Kunti urges her to take special care of her fifth husband, Sahadeva, as a mother! No other woman has had to face this peculiar predicament of dealing with five husbands now as spouse, then as elder or younger brother-in-law (to be treated like a father or as a son respectively) in an endless cycle.

Draupadi’s motherlessness seems to be carried forward into her own lack of maternal feelings. Her five sons are not even nurtured by her. She sends them to Panchala and follows her husbands into exile to ensure that the wounds of injustice and insult inflicted upon them and herself remain ever fresh.

Indeed, scholars beginning with Bankimchandra over a hundred years ago, have questioned the very fact of her maternity since, unlike the other Pandava progeny— Hidmimba’s Ghatotkacha, Subhadra’s Abhimanyu, Ulupi’s Iravan and Chitrangada’s Babhruvahana— Draupadi’s five sons are nothing more than names and might have been interpolated. The South Indian Draupadi cult specifically states that her sons were not products of coitus but were born from drops of blood that fell when, in her terrifying Kali form, her nails pierced Bhima’s hand.1 Draupadi is a sterile Shri, like Jyeshtha or Alakshmi. Her solitariness as a kanya is stressed explicitly after the war when Yudhishthira tells Gandhari that the Panchalas are exterminated, leaving only a kanya as their remainder: “pancalah subhrisham kshinah kanyamatra vasheshitah”.2

Ahalya and Satyavati are also not known for maternal qualities. Valmiki has not a word to say about the mother-son relationship between Ahalya and Shatananda. Ahalya’s son abandons her and lives comfortably in Janaka’s court, expressing relief that she is finally acceptable in society following Rama’s visit. Vyasa is abandoned by both parents and attributes his survival to chance (see issue 143). These kanyas remain quintessentially virgins and, except for Kunti, hardly ever assume the persona of mother.

This feature of being rejectedand-rejecting-in-turn that is a recurring leit motif with the kanya is not just of antiquary interest. It recurs in one of the most significant explorations of the Bengali woman’s struggle to step into the modern age by experimenting with new ways of motherhood: Ashapurna Debi’s trilogy Pratham Pratisruti, Subarnalata and Bakul Katha. The heroine, significantly named Satyabati, is “abandoned” by her father who gives her away in childmarriage at the age of eight. When she gives birth to her son, she simultaneously receives news of her mother’s death. She struggles to educate her children in a new urban milieu of a nuclear family. In her absence, her daughter Subarna is also married off at the age of eight. Thereupon Satyabati physically turns away from the wedding, abandoning her daughter on the threshold of motherhood, repeating the desertion she herself had experienced. The pattern repeats itself when Subarna, receiving news of her mother’s death, finds herself unable to think of her own daughter. It is a patriarchal society’s tradition of enforced motherlessness that the novels seek to challenge at the cost of the heroines being regarded as aberrant mothers. Ashapurna Debi questions the traditional concept of motherhood which confines woman to the role of a biological parent with no hand in shaping the future of the girl child. This is precisely what we notice in the case of the five kanyas. 3

Theme of Loss: The theme of loss is common to all the five kanyas. Ahalya has no parents, loses both husband and son and is a social outcast. Kunti loses her parents and then her husband twice over (first to Madri and then when he dies in Madri’s arms). Satyavati is abandoned by Parashara after he has enjoyed her, loses her husband Shantanu, both royal sons and one grandson (Pandu), while another is blind and the third cannot be king because her daughter-in-law Ambika deceived her and sent in her low-caste maid to Vyasa. The kingdom, for which she manoeuvred Devavrata into becoming Bhishma, slips through her fingers like sand. Seeing her great grandchildren at each other’s throats, she realises the grim truth of Vyasa’s warning, “the green years of the earth are gone” and leaves for the forest, so as not to witness the suicide of her race (I.128.6, 9). Strangely, her son Vyasa tells us nothing of her end.

Theme of Loss: The theme of loss is common to all the five kanyas. Ahalya has no parents, loses both husband and son and is a social outcast. Kunti loses her parents and then her husband twice over (first to Madri and then when he dies in Madri’s arms). Satyavati is abandoned by Parashara after he has enjoyed her, loses her husband Shantanu, both royal sons and one grandson (Pandu), while another is blind and the third cannot be king because her daughter-in-law Ambika deceived her and sent in her low-caste maid to Vyasa. The kingdom, for which she manoeuvred Devavrata into becoming Bhishma, slips through her fingers like sand. Seeing her great grandchildren at each other’s throats, she realises the grim truth of Vyasa’s warning, “the green years of the earth are gone” and leaves for the forest, so as not to witness the suicide of her race (I.128.6, 9). Strangely, her son Vyasa tells us nothing of her end.

Mandodari loses husband, sons, kith and kin in the great war with Rama. Tara loses her husband Bali to Rama’s arrow shot from hiding. Both have to marry their younger brothersin-law who are responsible for their husbands’ deaths (see issue 141). Draupadi finds her five husbands discarding her repeatedly. Each takes at least one more wife. She never has Arjuna for herself, as he marries Ulupi, Chitrangada and has Subhadra as his favourite. Yudhishthira pledges her like chattel at dice. Finally, they leave her to die alone on the mountainside at the mercy of wild beasts, like a pauper, utterly rikta, drained in every sense.4

In her long poem “Kurukshetra” Amreeta Syam conveys the angst of Panchali, born unasked for, bereft of father, brothers, sons and her beloved sakha Krishna:

“Draupadi has five husbands—but she has none— She had five sons—and was never a mother… The Pandavas have given Draupadi… No joy, no sense of victory No honour as wife No respect as mother — Only the status of a Queen… But they have all gone And I’m left with a lifeless jewel And an empty crown… my baffled motherhood Wrings its hands and strives to weep.”5

The Unique Ahalya: Among the five, Ahalya remains unique because of the nature of her daring and its consequence. Her single transgression, for having done what her femininity demanded, calls down an awful curse. Because of her unflinching acceptance of the sentence, both Vishvamitra and Valmiki glorify her. Chandra Rajan, another sensitive poet of today, catches the psychological nuances:

“Gautama cursed his impotence and raged… she stood petrified uncomprehending in stony silence withdrawn into the secret cave of her inviolate inner self… she had her shelter sanctuary benediction within, perfect, inviolate in the one-ness of spirit with rock rain and wind with flowing tree and ripening fruit and seed that falls silently in its time into the rich dark earth.”6

A very different evocation of Ahalya was done by Rabindranath Tagore in a lovely poem 7:

“What were your dreams, Ahalya, when you passed Long years as stone, rooted in earth, prayer And ritual gone, sacred fire extinct In the dark, abandoned forestashram? … Today you shine Like a newly woken princess, calm and pure. You stare amazed at the dawn world. … You gaze; your heart swings back from the far past, Traces its lost steps. In a sudden rush, All round, your former knowledge of life returns… Like first Created dawn, you slowly rise from the blue Sea of forgetfulness. You stare entranced; The world, too, is speechless; face to face Beside a sea of mystery none can cross You know afresh what you have always known.”

Symbols of Reselience: None of these maidens breaks down in the face of personal tragedy. Each continues to live out her life with head held high. This is one of the characteristics that set the kanya apart from other women.There is an aspect of exploitation that we notice in the ways the kanyas are treated. Sugriva hides behind Tara and uses her to calm the raging Lakshmana. Kuntibhoja uses Kunti to please Durvasa. Draupadi is used first by Drupada to take revenge on Drona by securing the alliance of the Pandavas, and then by Kunti and the Pandavas to win their kingdom thrice over (through marriage; in the first dice game; and as their incessant goad on the path to victory).8 Unknown to her, even sakha Krishna throws her in as the ultimate temptation in Karna’s way, assuring him that Draupadi will come to him in the sixth part of the day, shashthe ca tam tatha kale draupadyupagamisyati. 9

Symbols of Reselience: None of these maidens breaks down in the face of personal tragedy. Each continues to live out her life with head held high. This is one of the characteristics that set the kanya apart from other women.There is an aspect of exploitation that we notice in the ways the kanyas are treated. Sugriva hides behind Tara and uses her to calm the raging Lakshmana. Kuntibhoja uses Kunti to please Durvasa. Draupadi is used first by Drupada to take revenge on Drona by securing the alliance of the Pandavas, and then by Kunti and the Pandavas to win their kingdom thrice over (through marriage; in the first dice game; and as their incessant goad on the path to victory).8 Unknown to her, even sakha Krishna throws her in as the ultimate temptation in Karna’s way, assuring him that Draupadi will come to him in the sixth part of the day, shashthe ca tam tatha kale draupadyupagamisyati. 9

This is followed by Kunti urging Karna to enjoy (bhunkshva) Yudhishthira’s Shri (another name for Draupadi) that was acquired by Arjuna.10 There is an unmistakable harking back to Kunti’s command to her sons to enjoy (bhunkteti) what they had brought together when Bhima and Arjuna had announced their arrival with Draupadi as alms. No wonder Draupadi laments that she has none to call her own, when even her sakha unhesitatingly uses her as bait! We cannot but agree with Naomi Wolf’s condemnation of masculine culture’s efforts to “punish the slut” in one way or another, the sexually independent woman who crosses the ambiguous lakshmana-rekha separating “good” from “bad”.11

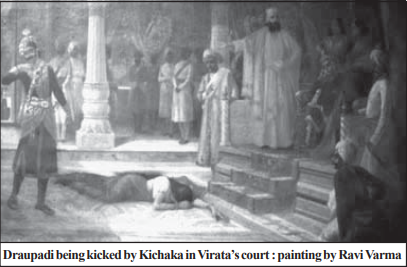

Vimla Patil, editor of Femina, writes, “Most Indian women would agree that, like this passionate heroine of the Mahabharata, millions of women are publicly humiliated and even raped as a punishment for challenging the male will or for ‘talking back’ at a man. Many men are known to use violence against wives merely because they ‘backanswer’!”15 Draupadi made the unforgivable ‘mistake’ of publicly refusing to accept Karna as a suitor and of laughing at Duryodhana (as he laments to his father Dhritarashtra) when he made a fool of himself in Indraprastha’s magical palace, capping this with refusing to obey Duryodhana’s summons to appear in the dice-game assembly unless her question was answered. She had to be taught a lesson.

Patriarchal Myth Making: A telling example of patriarchal rewriting occurs in Kashiram Das’ early 18th century version of the epic in Bengali rhyme.16 During the forest exile Draupadi prides herself on her fame as a sati exceeding that of any ruler. Krishna crushes her pride by creating an unseasonal mango that she craves for and has Arjuna pluck for her. Krishna warns that this is the only food of a terrible ascetic, whose anger will turn all of them into ashes, and that only if they confess their secret desires will the mango be refixed to its branch. The mango almost touches the tree as the brothers state what obsesses each of them, but falls down when Draupadi states that revenge is her sole desire. Arjuna threatens to kill her, and then she has to confess that having Karna as her sixth husband has been her secret wish. Bhima—her invariable rescuer—upbraids her unmercifully for her evil nature.

Here we have evidence of a male backlash expressed through inventive myth-making. This attitude is well reflected in a report in the newspaper The Hindu of a discourse by a lady, Jaya Srinivasan, echoing the patriarchal response12 :

“It is indeed extremely difficult to control the mind as reflected in all scriptural texts. Even sensory organs may be kept quiet for some time, but not the mind. It is in this background that the Ahalya episode in the Ramayana should be viewed. Born in a family of culture and having married a sage of distinction, her mind faltered for a moment and she committed a grave sin and incurred a curse. Why should she commit this mistake? There lie the lessons for others. However on expressing her regret over the fault, the curse was lifted when the dust particles from the feet of Rama fell on her. The message from her life gives us great hope to secure His grace if only we hold on to the feet of the Lord… What Ahalya did was unpardonable and Sage Gautama, naturally enraged at her misconduct, condemned her.” (Emphasis in the original)

Cults of Draupadi: There is, however, a feature that sets Draupadi quite apart from her fellow kanyas. Between the 12th and 15th centuries she became the central figure in a number of bardic epics. Draupadi is the only kanya to whom a living cult is dedicated, with temples dotting the GingeePondicherry area of Tamil Nadu and street plays held annually celebrating her greatness. By reincarnating as Bela in the Rajasthani Alha, and subsequently as Yakajoti, the Rani of Raja Desing in the south, she completes her cycle of seven births as sati. In Yakajoti’s story, Hiltebeitel points out, we encounter war cries invoking Allah, Hari and Govinda along with wedding chants calling on Allah and Radha, showing the Hindu-Islamic syncretism that had developed by then. These oral epics celebrate Dalit and Muslim protectors of the protagonists, giving a new currency to the Sanskrit epic lore.13

Intriguingly, where the so-called “Dravidian” political backlash against “Aryan” hegemony targeted traditional icons like Rama and Sita and even burnt copies of the Ramayana, not a word was said or written against Draupadi and her temples. Analysing the reasons, the eminent scholar Dr. Prema Nandakumar draws a perceptive distinction between the two great epic heroines:

Intriguingly, where the so-called “Dravidian” political backlash against “Aryan” hegemony targeted traditional icons like Rama and Sita and even burnt copies of the Ramayana, not a word was said or written against Draupadi and her temples. Analysing the reasons, the eminent scholar Dr. Prema Nandakumar draws a perceptive distinction between the two great epic heroines:

“Sita is the patient compassionate mother whose fire remains veiled by her soft approach, but Draupadi is quite different. Whereas Sita is generally associated with the upper caste (Aryan) hegemony, Draupadi has always been the goddess of the common people. A recent parallel would be the way Meera’s bhajans are sung by the marginalized and lower castes in Rajasthan. The Dropadai Amman Festivals are quite well known and there are night-long dramas (therukoothu) on the Mahabharata. The political leaders knew this social reality, I think, so they did not dare to say anything against her or burn the Mahabharata or write nastily about her. For the marginalized would have protested in a big way…Even after becoming legends, it is Draupadi who remains a threat to the political animal and so he will not touch even the fringe of her pallu, as he knows what happened when Duhshasana rose to disrobe Draupadi! Not so Sita. Either the legend will not fight back or it is so compassionate the political animal can get away with its desecration and be forgiven too.”19

Contrast with Sita: Curiously, it is women scholars who cannot seem to agree on this. This insight from a Tamil scholar is contradicted by Dr. Nabaneeta Dev Sen from Bengal. Studying the folk songs of Telugu, Tamil, Maithili and Bengali on Sita, she states,

“No, a revengeful woman cannot win…Draupadi is too dramatic to be a role model for the weak and the exploited. Women cannot identify with Draupadi, with all her five husbands, and with Lord Krishna for a personal friend. With her unconventional lifestyle and thirst for vengeance, Draupadi inspires awe. Sita is a figure closer home…she is not part of the elite…she laments but does not challenge Rama in the songs…Sita is the one with infinite forbearance and thus a winner even when she loses.”20

Dev Sen appears to be ignorant of the popularity of the Mahabharata street plays, theru-koothu, and the Draupadi Cult celebrated exclusively by villagers. And, as Dr. Prema Nandakumar points out apropos Draupadi being too dramatic:

“any woman whom a huge hulk of a fellow tries to disrobe in public while the entire Pandava-Kaurava ‘heroes’ look on (perhaps leeringly?) doing nothing will scream throughout her life and will not speak in ambassadorial accents across the table. The real truth about the matter is that we are both (Sita and Draupadi), we need both, we identify with both as the circumstances demand of us.”21

Draupadi is also the only kanya to have become a symbol of the oppressed and grossly humiliated Indian nation. While watching a night long street play in the Draupadi Amman Festival,the great Tamil poet Subramania Bharati was struck by the powerful appeal she had for common folk and penned an epyllion, Draupadi Sapatham (“Draupadi’s Vow”) depicting her as the wronged princess, the nation-in-shackles, a symbol of perfect surrender to the Divine and the representative of womanhood subjugated for millennia.22

An outstanding instance of how Draupadi’s character speaks powerfully to oppressed womanhood today is vividly brought alive in Mahasweta Devi’s remarkable short story, “Dopdi” in which this name is given to a tribal woman who refuses to succumb despite gang-rape and torture.

The Cross of Lonliness: The kanya, despite having husband and children, remains alone to the last. This is the loneliness at the top that great leaders bear as their cross. The absence of a mother’s nurturing, love, a mother who models and hands down tradition, leaves the kanya free to experiment, unbound by shackles of taught norms, to mould herself according to her inner light, to express and fulfil her femininity, achieving selfactualisation on her own terms. One is tempted to use a modern cliché to describe her: a woman of substance. 23 An invaluable insight into what is so very special in being a woman—virgin, wife and mother—is found in what an Abyssinian woman told Frobenius. In her words we find the reason for our kanyas remaining such an enigma to men throughout the ages:

The Cross of Lonliness: The kanya, despite having husband and children, remains alone to the last. This is the loneliness at the top that great leaders bear as their cross. The absence of a mother’s nurturing, love, a mother who models and hands down tradition, leaves the kanya free to experiment, unbound by shackles of taught norms, to mould herself according to her inner light, to express and fulfil her femininity, achieving selfactualisation on her own terms. One is tempted to use a modern cliché to describe her: a woman of substance. 23 An invaluable insight into what is so very special in being a woman—virgin, wife and mother—is found in what an Abyssinian woman told Frobenius. In her words we find the reason for our kanyas remaining such an enigma to men throughout the ages:

“How can a man know what a woman’s life is?…He is the same before he has sought out a woman for the first time and afterwards. But the day when a woman enjoys her first love cuts her in two…The man spends a night by a woman and goes away. His life and body are always the same…He does not know the difference before love and after love, before motherhood and after motherhood…Only a woman can know that and speak of that. That is why we won’t be told what to do by our husbands. A woman can only do one thing…She must always be as her nature is. She must always be maiden and always be mother. Before every love she is a maiden, after every love she is a mother.”24 (emphasis mine)

We have only to recall the encounters of Surya, Dharma, Vayu, Indra and Pandu with Kunti, of Parashara and Shantanu with Gandhakali, of Draupadi with her husbands, of Ulupi with Arjuna, of Indra with Ahalya, to realise the profundity of this utterance.

Autonomy Inspires Awe: C.G. Jung, while discussing the phenomenon of the maiden describes her “as not altogether human in the usual sense; she is either of unknown or peculiar origin, or she looks strange or undergoes strange experiences”.25 This fits the kanyas as a group. So long as a woman is content to be just a man’s woman, she is devoid of individuality and acts as a willing vessel for masculine projections. On the other hand, the maiden uses the Anima of man to gain her natural ends (Bernard Shaw called it the Life Force). Amply do we see in the cases of these maidens that, “The Anima lives beyond all categories, and can therefore dispense with blame as well as with praise.”14 The Anima is characterised by “a secret knowledge, a hidden wisdom…something like a hidden purpose, a superior knowledge of life’ laws”15 which we see in this group of epic women. That is why Shantanu, Bhishma, Dhritarashtra, Pandu, the Kaunteyas, Sugriva can never quite come to grips with Satyavati, Kunti, Draupadi and Tara and are ever in awe of them.

Autonomy Inspires Awe: C.G. Jung, while discussing the phenomenon of the maiden describes her “as not altogether human in the usual sense; she is either of unknown or peculiar origin, or she looks strange or undergoes strange experiences”.25 This fits the kanyas as a group. So long as a woman is content to be just a man’s woman, she is devoid of individuality and acts as a willing vessel for masculine projections. On the other hand, the maiden uses the Anima of man to gain her natural ends (Bernard Shaw called it the Life Force). Amply do we see in the cases of these maidens that, “The Anima lives beyond all categories, and can therefore dispense with blame as well as with praise.”14 The Anima is characterised by “a secret knowledge, a hidden wisdom…something like a hidden purpose, a superior knowledge of life’ laws”15 which we see in this group of epic women. That is why Shantanu, Bhishma, Dhritarashtra, Pandu, the Kaunteyas, Sugriva can never quite come to grips with Satyavati, Kunti, Draupadi and Tara and are ever in awe of them.

Each kanya’s unique feature is that she, as much as the sati, has the power to pronounce a curse. Devayani curses Kacha that he will be unable to use the mantra he has learnt from her father Shukracharya by her favour. Urvashi curses Arjuna to lose his virility because he refuses to respond to her advances. Rambha, another apsara, curses Ravana with death should he rape any female in future. Vedavati curses Ravana that she will be the cause of his death. Amba turns herself into Bhishma’s nemesis. Ganga, turned down by Pratipa, enchants his son Shantanu: “He stood there, Entranced, All his body In horripilation. With both eyes He drank in her beauty And wanted To drink more.”17

Jung pinpoints the desymbolised world we live in now, in which man struggles to relate to his Anima “outside” himself by projecting her on numerous women although, paradoxically, she is the psyche within that he must commune with. That, perhaps, is the message hidden behind the hint to keep ever fresh the memory of the five maidens so that we become conscious of the Anima projection.

Sati Versus Shakti: In this context, the mystic and poet Nolini Kanta Gupta’s study of these maidens tallies quite remarkably with the Jungian insight into the meaning of being a virgin. He points out, “In these five maidens we get a hint or a shade of the truth that woman is not merely sati but predominantly and fundamentally she is Shakti”.18 He notes how the epics had to labour at establishing their greatness in the teeth of the prejudice that woman must never be independent, but always be a sati, known for her absolute, unquestioning devotion to her husband. This he describes as the subjugation of Prakriti to Purusha, typical of the Middle Ages. The most ancient relationship, he says, was the converse: Shiva under the feet of his goddess-consort.

Sati Versus Shakti: In this context, the mystic and poet Nolini Kanta Gupta’s study of these maidens tallies quite remarkably with the Jungian insight into the meaning of being a virgin. He points out, “In these five maidens we get a hint or a shade of the truth that woman is not merely sati but predominantly and fundamentally she is Shakti”.18 He notes how the epics had to labour at establishing their greatness in the teeth of the prejudice that woman must never be independent, but always be a sati, known for her absolute, unquestioning devotion to her husband. This he describes as the subjugation of Prakriti to Purusha, typical of the Middle Ages. The most ancient relationship, he says, was the converse: Shiva under the feet of his goddess-consort.

In the Mahabharata we find confirmation of this paradigm shift. In the course of his pilgrimage, Balarama comes to the Plaksha Prasravana teertha where a brahmacharini, a celibate female ascetic, obtained the highest heaven and the supreme yoga as well as the fruit of a horse sacrifice. However, Balarama also visits the Vriddhakanya teertha celebrated for an old spinster who had to learn that, unless she married she could not, as a mere brahmacharini, attain heaven!19

The Age of Freedom: In Mahabharata, we find evidence of the freedom enjoyed by women in the past. In the Adi Parva Pandu tells Kunti: “in the past, women were not restricted to the house, dependent on family members; they moved about freely, they enjoyed themselves freely. They slept with any men they liked from the age of puberty; they were unfaithful to their husbands, and yet not held sinful… the greatest rishis have praised this tradition-based custom;… the northern Kurus still practise it… the new custom is very recent.”20

Pandu narrates the story of Uddalaka explaining to his outraged son Shvetaketu, when a Brahmin takes his mother away in their presence, “This is the Sanatana Dharma. All women of the four castes are free to have relations with any man. And the men, well, they are like bulls.”21 Ulupi and Urvashi’s behaviour with Arjuna and Ganga’s with Pratipa and Shantanu—all approaching the men with frank sexual demands—are instances of the type of freedom characterising the kanya’s nature. In these kanyas, we find the validation of Naomi Wolf’s celebration of women as “sexually powerful magical beings”.22 By the time of Pandu, however, the Aryans settled around the SarasvatiYamuna region had started looking down upon their Northern brethren and even classed them—such as the Madras—with Mlecchas, nonAryans. When Karna lashes back at Shalya for abusing him, he criticises the loose morals of Madra women because they enjoy themselves with fish, beef and wine, express their emotions uninhibitedly and mix freely with men.23

Mode of Elements: O ne interpretation of why the epithet kanya is applied to these women is because they were not engendered in the usual way “but were created from various elements which compose the universe thereby establishing that their sanctity and chastity is not bound by physical bodies…Ahalya, Sita, Draupadi, Tara and Mandodari are the epitome of chastity and purity but were punished for no fault of theirs. Given the precarious situations they were in, these women still came out unscathed and set examples of being ideal women.”24 Vimla Patil, former editor of Femina, links each kanya to one of the elements:

ne interpretation of why the epithet kanya is applied to these women is because they were not engendered in the usual way “but were created from various elements which compose the universe thereby establishing that their sanctity and chastity is not bound by physical bodies…Ahalya, Sita, Draupadi, Tara and Mandodari are the epitome of chastity and purity but were punished for no fault of theirs. Given the precarious situations they were in, these women still came out unscathed and set examples of being ideal women.”24 Vimla Patil, former editor of Femina, links each kanya to one of the elements:

“Are you an ‘earth’ woman? Do you feel an affinity to the element of ‘fire’ because of your passionate nature? Do you flow serenely through life like “water’? Is your spirit free and elusive like the ‘wind’? Or do you dream of being light as air and vast like ‘space’? As an Indian woman, it is likely that you have a little of all these elements in you and that you combine all qualities of the five elements. If this is so, you should not be surprised, for…all Indian women carry the legacy of their icons, the most celebrated panchkanyas of mythology …In fact, the five women have such a powerful hold over the hearts of millions of Indians that they are called the panchkanyas (five women) whose very names ensure salvation and freedom from all evil. It is not uncommon for devout Hindus to recite their names each morning in a Sanskrit shloka to remind them of the power they symbolised because of their spiritual strength…in truth, every Indian woman has shades of all the panchkanyas within her soul!”25

This is a modern restatement of a traditional belief that is part of the Mahari dance tradition in which the Oriya verse goes:26

Pancha bhuta khiti op tejo maruta byomo

Pancha sati nirjyasa gyani bodho gomyo

Ahalya Draupadi Kunti Tara Mandodari totha

Pancha kanya…

Five elements, earth, water, fire, wind, ether

Are in essence the five satis.

This the wise know Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, Tara and Mandodari

Five virgins…

Ahalya personifies water, Draupadi represents fire, Kunti symbolises mother earth, Tara personifies wind and Mandodari ether. However, Dr.Ratna Roy, leading exponent of the Panchakanya Mahari dance, feels that this equation of each element representing one of these women cannot be substantiated. For her the emphasis is on the purity of these women because they did not break any humanistic codes, only the strictures of their orthodox patriarchal society that undermines women such as the Maharis.27

On the other hand, for Vimla Patil Draupadi’s personality personifies fire, while Sita (whom she incongruously includes in the group instead of Kunti) is the daughter of the earth. Ahalya “for her forbearance is likened to the freshness and active nature of the wind”; Tara (all the three women of that name, that is, Harishchandra’s queen, Vali’s wife and Brihaspati’s wife who is Chandra’s beloved) is associated “with space and has the quality of intelligence, compassion and largeheartedness”; Mandodari “with the element of water, turbulent on the surface yet deep and silent in her spiritual quest.” Pointing out that the Pancha Kanya are living role models for Indian women, she writes,

“Like their icons, they have dual personalities. They are bound by the strictest norms of society, on the one hand; yet, on the other hand, they are left free to prolifically use the chinks in the armour of social and traditional laws made by a staunchly male-oriented pecking order. Within the scope of social boundaries, they can still express their personalities and design their own life-graphs…The life-graph of each of these women is somehow replicated in the lives of millions of Indian women even today… The panchkanya theme has inspired Indian women for eons… Most Indian women believe that they tolerate and accept the worst kind of injustice like Sita and remain steadfast in their duty and devotion to their husbands and families. Yet, surprisingly, like Draupadi, they also hide storms of anguish anger and revenge in their hearts. They believe that the curse of a virtuous, strong woman can ruin the most powerful of men. Like Mandodari, they live a life of duality, with the turbulence of varied experiences on the surface and a deep, silent core in their souls, where wisdom originates. Like Mandodari, they have an inherent gift of distinguishing between right and wrong. In a crisis, they know how to insist on doing what they consider right. Like Ahilya, (sic.) they have a dormant power buried deep down in their psyches. They have the strength to move like the wind and the compassion to forgive wrongs done to them. Like Tara, they seek a special lustre of their own. They seek a sacred place— which is their right—in the vastness of space. From this niche, they spread their compassion and tenderness. It is for every woman to study the life-graphs and personalities of the panchkanyas and decide which element they empathise with.”28

Attempts at Sanitisation: Nolini Kanta Gupta makes an extremely perceptive comment on how the patriarchal system has sought to sanitise the kanyas’ dangerous independence by projecting them as satis instead: “We moderns also, instead of looking upon the five maidens as maidens, have tried with some manipulation to remember them as sati. We cannot easily admit that there was or could be any other standard of woman’s greatness beside chastity…Their souls did neither accept the human idea of that time or thereafter as unique, nor admit the dharma-adharma of human ethics as the absolute provision of life. Their beings were glorified with a greater and higher capacity. Matrimonial sincerity or adultery became irrelevant in that glory…Woman will take resort to man not for chastity but for the touch and manifestation of the gods, to have offspring born under divine influence… a person used to follow the law of one’s own being, one’s own path of truth and establish a freer and wider relation with another.”29

It is the ability to distinguish the masculine power of logos, the power of words, of thought, of will and of acting in the outside world, that makes the kanyas so significant to women today. From their lives we can learn how to integrate successfully the masculine in the feminine, without one overwhelming the other. Each of them is a telling example of this, perhaps Kunti most of all. We have seen it in her ability to take the toughest decisions, her using the story of Vidula, her building a special relationship with Vidura and, above all, in her farewell, “calm of mind, all passion spent” for, “The Animus power…makes possible the development of a spiritual attitude which sets us free from the limitation and imprisonment of narrowly personal standpoint.”30

Emma Jung sums up the crucial importance of integrating the feminine and the masculine that the five kanyas represent uniquely: “In our time, when such threatening forces of cleavage are at work, splitting peoples, individuals, and atoms, it is doubly necessary that those which unite and hold together should become effective; for life is founded on the harmonious interplay of masculine and feminine forces, within the individual human being as well as without.”31 That is why the exhortation to recall the five virgin maidens is so relevant now. The past does indeed hold the future in its womb.

Endnotes:

1. A. Hiltebeitel Cult of Draupadi, University of Chicago Press, 1988, vol. I, p. 293.

2. Mahabharata, 15.44.32.

3. Indira Chowdhury: “Rethinking Motherhood, Reclaiming a Politics”, Economic & Political Weekly, XXXIII.44, 31.10.1998, pp. WS-47 to 52.

4. Shaonli Mitra has Bhima come up to her at the end and ask, “Are you in much pain, Panchali?” She answers, “In the next birth, be mine alone, Bhima, so that I may rest a little, my head in your lap.” Nathaboti Anathabot M.C. Sirkar & Sons, Calcutta, 1990, p.69.

5. Amreeta Syam: Kurukshetra (Writers Workshop, Calcutta, 1991, pp. 38-9). Other notable interpretations of Draupadi’s lot are Dr. Pratibha Ray’s Oriya novel Yajnaseni(Englished by Pradip Bhattacharya, Rupa, 1995), Dr. Chitra Chaturvedi’s Hindi novel Mahabharati (Jnanpith Prakashan, 1986) and Dr. Dipak Chandra’s Bengali novel Draupadi Chirontoni (Dey Books, Kolkata).

6. Chandra Rajan: Re-visions (Writers Workshop, Calcutta, 1987, p. 12).

7. Ahalya https://www.kundu.u-net.com/ radice1.htm by Rabindranath Tagore translated by William Radice.

8. The Bengali tele-serial Draupadi dwells upon this issue.

9. Udyoga Parva, 134.16 (pointed out by Dr. Nrisingha Prasad Bhaduri in “Draupadi”, Barttaman, annual number1396 B.S.).

10. ibid. 135.8.

11. Naomi Wolf, best-selling feminist author and advisor to the American President and Vice-President, in Promiscuities quoted in TIME, 8.11.1999, p. 25.

12. The Hindu(www.hinduonnet.com/2002/ 09/30/stories/2002093003240900.htm) Sept. 30, 2003.

13. Alf Hiltebeitel: Rethinking India’s Oral and Classical Epics University of Chicago Press, 1999.

14. C.G. Jung: The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Routledge, p. 28- 29.

15. ibid. p. 31.

16. https://www.iskcon.org/gallery/002/ 006.htm painting by Puskar Das (Matthew Goldman)

17. Ibid. 1.97.28.

18. Mother India, June 1995, pp. 439-443.

19. Mahabharata IX.53.4-8 and 50.51-24 quoted in A. Hiltebeitel, Rethinking the Mahabharata, University of Chicago Press, 2001, p.145.

20. Mahabharata 1.122.4-8.

21. Ibid.1.122.13-14.

22. Gupta op.cit.

23. Mahabharata, Karna Parva, 26-28, 37 42: “Women mix freely with men known and unknown…They eat fish, beef, drink wine, cry, laugh, sing and talk wildly and indulge in promiscuity.”

24. Deccan Herald, 27.4.2003, “Panchakanya ballet today” referring to danseuse Vani Ganapathy’s performance.

25. The Tribune online edition 27.10.2002, http://www.tribuneindia.com/2002/20021027/ herworld.htm#1

26. Dr. Ratna Roy, personal communication.

27. Personal communication. Also see http://www.olywa.net/ratna-david panchakanya.htm

28. Vimla Patil op.cit.

29. Gupta op.cit.

30. Ibid. p.40.

31. ibid.

https://withoutprescription.guru/# viagra without a doctor prescription walmart

ed meds online without prescription or membership: viagra without a doctor prescription – meds online without doctor prescription

https://withoutprescription.guru/# non prescription ed pills

can i buy prednisone online without prescription: prednisone pharmacy prices – where to buy prednisone 20mg no prescription

canadianpharmacyworld: Buy Medicines Safely – canadian pharmacy 365

https://withoutprescription.guru/# buy prescription drugs from canada cheap

non prescription ed drugs: best non prescription ed pills – viagra without a doctor prescription

amoxicillin 500mg price: amoxicillin 500mg price – buy amoxicillin over the counter uk

best online pharmacies in mexico: mexico drug stores pharmacies – best online pharmacies in mexico

https://indiapharm.guru/# cheapest online pharmacy india

cheap erectile dysfunction pill: best treatment for ed – new ed pills

https://edpills.monster/# the best ed pill

cheap kamagra sildenafil oral jelly 100mg kamagra buy kamagra online usa

https://tadalafil.trade/# 60 mg tadalafil

cheap kamagra: Kamagra tablets – buy Kamagra

Generic Levitra 20mg Buy generic Levitra online Buy Vardenafil 20mg online

https://tadalafil.trade/# where can i buy tadalafil

sildenafil rx coupon: sildenafil 50mg united states – sildenafil citrate women

medicine erectile dysfunction medications for ed buy ed pills online

https://tadalafil.trade/# best price tadalafil 20 mg

https://tadalafil.trade/# tadalafil 2

sildenafil 10 mg price: sildenafil generic in united states – how to buy sildenafil online

tadalafil 5mg in india: tadalafil mexico price – cheapest tadalafil india

cheap sildenafil 50mg uk 30 mg sildenafil buying sildenafil uk

https://tadalafil.trade/# tadalafil 5 mg coupon

https://doxycycline.forum/# doxycycline tablets in india

zestoretic canada buy lisinopril online lisinopril 5 mg buy online

amoxicillin 875 125 mg tab: amoxil for sale – buy amoxicillin 500mg

can you buy amoxicillin uk: amoxil for sale – amoxicillin in india

https://ciprofloxacin.men/# buy cipro without rx

buy ciprofloxacin over the counter: ciprofloxacin without insurance – cipro online no prescription in the usa

zestril 10 Over the counter lisinopril buy lisinopril 20 mg online canada

https://ciprofloxacin.men/# where to buy cipro online

cipro ciprofloxacin: Get cheapest Ciprofloxacin online – buy cipro online without prescription

discount doxycycline Doxycycline 100mg buy online doxycycline rx coupon

https://doxycycline.forum/# doxycycline 200 mg price in india

buy amoxicillin 500mg capsules uk: amoxil generic – amoxicillin 500 mg brand name

where can i get zithromax zithromax 500 mg lowest price pharmacy online buy zithromax 1000 mg online

https://azithromycin.bar/# zithromax cost

buy generic ciprofloxacin: ciprofloxacin without insurance – cipro for sale

zestril 40: Over the counter lisinopril – rx 535 lisinopril 40 mg

cipro Get cheapest Ciprofloxacin online buy cipro

https://ciprofloxacin.men/# buy cipro no rx

cipro: buy ciprofloxacin online – buy ciprofloxacin over the counter

https://indiapharmacy.site/# pharmacy website india

canada ed drugs: accredited canadian pharmacy – canada drug pharmacy

mexican drugstore online: mexican online pharmacy – medicine in mexico pharmacies

my canadian pharmacy rx Online pharmacy USA best online pharmacy

https://canadiandrugs.store/# medication canadian pharmacy

safe canadian online pharmacies: Mail order pharmacy – canadian pharmacy drugstore

reputable mexican pharmacies online: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican mail order pharmacies

https://indiapharmacy.site/# online pharmacy india

canada pharmacy: certified canadian pharmacy – legit canadian pharmacy

escrow pharmacy canada trust canadian pharmacy canadian pharmacies

medications without prescription: order medication online – canadian pharmacy order

https://gabapentin.life/# buy generic neurontin online

wellbutrin 450 mg: Buy Wellbutrin XL 300 mg online – zyban wellbutrin

https://claritin.icu/# ventolin otc uk

buy paxlovid online: buy paxlovid – paxlovid price

https://claritin.icu/# ventolin generic price

paxlovid pharmacy: cheap paxlovid online – paxlovid generic

paxlovid india https://paxlovid.club/# paxlovid pill

https://clomid.club/# can i get generic clomid without insurance

clomid without insurance: Buy Clomid Online – where can i buy generic clomid without insurance

https://wellbutrin.rest/# best generic wellbutrin 2015

https://clomid.club/# generic clomid

ventolin australia: Ventolin inhaler best price – buy generic ventolin

https://claritin.icu/# cheap ventolin online

top farmacia online: comprare avanafil senza ricetta – farmacia online migliore

farmacia online senza ricetta kamagra gel prezzo farmacia online miglior prezzo

top farmacia online: avanafil prezzo in farmacia – top farmacia online

farmacie online autorizzate elenco: farmacia online spedizione gratuita – farmacie online affidabili

https://kamagrait.club/# comprare farmaci online all’estero

comprare farmaci online all’estero: farmacia online spedizione gratuita – farmacia online migliore

dove acquistare viagra in modo sicuro: viagra online spedizione gratuita – viagra originale in 24 ore contrassegno

farmacia online piГ№ conveniente kamagra oral jelly farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

top farmacia online: avanafil generico prezzo – comprare farmaci online con ricetta

viagra generico prezzo più basso: viagra prezzo – viagra generico sandoz

farmacie on line spedizione gratuita: acquistare farmaci senza ricetta – farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

https://sildenafilit.bid/# viagra naturale

farmacie online sicure: farmacia online miglior prezzo – farmacie online autorizzate elenco

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: kamagra gel – farmacia online più conveniente