This was first published in the print edition of Manushi journal, Issue no. 153 of 2006.

The first evidence of dance in Orissa dates to the 2nd century BC, in the iconographical representation of a female dancer with four female musicians. The panels are situated in the Rani Gumpha cave in Bhubaneswar, in what scholar and theatre director, Sri Dhiren Dash, proved was a Sanskrit theatre venue.1 Since the 10th century AD, the dance has been performed by female temple dancers (Maharis) in Orissa, particularly in the temple of Lord Jagannatha. Around the 15th century AD, the gotipua tradition was born, with young boys impersonating females. Both traditions of dance continued in Orissa during Muslim rule in India, although the former went underground several times due to Muslim attacks on the temple.

During British colonial rule, both styles debilitated due to lack of patronage, attack on the Mahari institution by nationalists and Brahmin patriarchy, and proselytizing by Christian missionaries. The dance style was reconstructed in the 50’s and 60’s of the 20thcentury by a group of scholars and dancers who are now gurus. Today, classical or neo-classical Odissi dance is an established tradition, based on the formulations of the society, Jayantika, created for the preservation of the dance in the 1960’s. The principal players in Jayantika were Kabichandra Kali Charan Patnaik, Lokanath Mishra, and D. N. Patnaik, as scholars, and Guru Kelu Charan Mohapatra, Guru Mayadhar Raut, and Guru Raghunath Dutta, as erstwhile gotipua dancers. Guru Pankaj Charan Das, the adopted son of a Mahari dancer, was left out of the equation, along with the Maharis themselves, because of the attack on the mahari institution and postcolonial sensibilities.

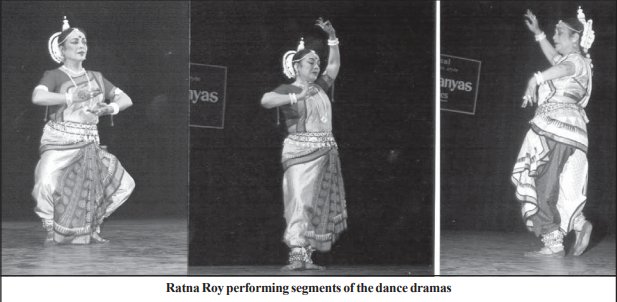

Thematically, in Orissa, the dances most often revolve around the two epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, or the tales of Krishna. Guru Pankaj Charan Das has choreographed five solo dance dramas that he called “items”, with five females from the two epics as the central characters: Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, Tara, and Mandodari, with Ahalya, Tara, and Mandodari from the Ramayana and Draupadi and Kunti from the Mahabharata. As a male brought up in the world-view of the Maharis, Guru Pankaj Charan Das provided the female point of view in an uneasy marriage with the dominant male perspective in these dance dramas. This article explores the factors that make Guru Pankaj Charan Das thematically so different from his peers.

Born on March 17, 1921, Guru Pankaj Charan Das was raised in a family of Mahari dancers. Destitute after the death of his father, Dharmacharan Das, his mother went with him to Mati Mandap Sahi in Puri, to the house of Fakira Mahari and Ratnaprabha Mahari for adoption into temple life. He grew up surrounded by devotional temple music and dance and was initiated into dance at the age of eight. His memories of those days are tinged with sadness: “Those who sang and danced were looked down upon by society as if they were sinners, without caste or gotra. We had a separate barber and washerman. We were like untouchables. Why are those who do Lord Jagannatha’s seva looked down upon by society? If society likes singing and dancing, why are the practitioners treated like scum? I got angry and jealous. But what was the use? I was brought up by such a family. Who would listen to me?” (translation mine).

Born on March 17, 1921, Guru Pankaj Charan Das was raised in a family of Mahari dancers. Destitute after the death of his father, Dharmacharan Das, his mother went with him to Mati Mandap Sahi in Puri, to the house of Fakira Mahari and Ratnaprabha Mahari for adoption into temple life. He grew up surrounded by devotional temple music and dance and was initiated into dance at the age of eight. His memories of those days are tinged with sadness: “Those who sang and danced were looked down upon by society as if they were sinners, without caste or gotra. We had a separate barber and washerman. We were like untouchables. Why are those who do Lord Jagannatha’s seva looked down upon by society? If society likes singing and dancing, why are the practitioners treated like scum? I got angry and jealous. But what was the use? I was brought up by such a family. Who would listen to me?” (translation mine).

The girls in the family were taught to dance. He would watch from the window and imitate them. He recalled how good he was at imitating the movements of the girls and how jealous the girls were of his capabilities. He learnt mahari dance from his aunt, and the Rasa Leela style of abhinaya and dance from Guru Ranganath Dev Goswami and Bhikhari Charan Dalei. The highlights of the Guru’s childhood life consisted of the times he was allowed to act in school plays and the praises he received for his voice. His singing got him the honour of Bada Chatta, a service attached to the temple. Failing his high school exam three times, he gave up on education. But the theatre of the road, the people’s theatre, thrilled him. However, the death of his adopted mother forced him to hunt for a job to survive. He sang and danced at the newly formed theatre of Bala Bhadra Hajuri.

“I grew older and needed more money. I wanted better clothes. So, in my Sahi, I started a paan shop. If jatras came, I would sell a lot. I would sing and make money. I always thought of how to earn money. I became a referee for gamblers and went to the thana and paid fines. After paying fines, I decided not to stay in this Sahi “Then, in Pikapara stage, I became a hawker. Whatever the bosses wanted, I did. I also took part in drama. The drama was staged all night long. the I sold soda water from a vendor cart. While pushing the cart around, I sang songs. I would imitate the songs and dances in the movies. After midnight, people would request my imitations. My commission increased — instead of one anna, I received 5-10 paisa.”

When Kalibabu’s theatre came to Puri, the urge to join big-time theatre gained ground. After two ventures from Cuttack to Balasore, including the one with the New Theatres, Pankaj Charan Das returned to Puri. He met Kelu Charan Mohapatra through Radha Govinda’s theatre party. Finally, they both joined the Annapurna Theatre B, after the split-up of the Annapurna theatre, where he was Dance Director from 1942 to 1948.

It was here that dance was instituted as an interlude to serious drama in the tradition of Sanskrit theatre. Pankaj Charan Das choreographed Vasmasura as the dance director with Kelucharan as Shiva and Laxmipriya (who was later to become Kelucharan’s wife) as Mohini. The dance was a hit. As Guru Pankaj Charan Das admits, the Mahari dance had no stylized hand gestures and postures. It was the outpouring of a soul to her husband, who also happened to be God himself. The language of the soul was central, and the face, inasmuch as it conveyed the non-verbal language of the soul, was the vehicle for expression. The Mahari dance, as imbibed by Pankaj Charan Das, had to be modified to suit the theatre. “Then I established my own style,” said Pankaj Charan Das. It was Odissi, the language of the people, the language of the land, the language of the roadside theatre blended with the private language of two souls in communion, one of them being the allknowing God himself.

“In 1946, I started Odissi dance in my own style in Aswini Kumar’s drama, Abhiseka. Before this, Odissi was never performed in traditional dramas.” He mused to Jimuta Mangaraj and Umapada Bose, “But the dance is a reflection of the Bhakti bhava. It is characterized by lasya. That is called thani. The dancer becomes totally involved and dances before the Lord. The dancers of today are so selfconscious that their dance looks harsh. There is no stamina… Mostly dancers dance for their own pleasure. How can they achieve fulfillment?” Yet the guru himself remained unfulfilled as he languished in Orissa with the few dancers trained under him exclusively to carry on his distinctive style.

From his own recounting of his life, what is evident is that (a) the guru grew up in a spiritual tradition within the context of growing secularization and eventual commodification of Odissi; (b) in spite of his upbringing in a Mahari family, his own style evolved in the theatre; (c) he was raised among the Maharis at a time when the Devadasi Bill was becoming a reality in the South, when power was imbalanced in favour of the male in a society; (d) he was practicing a dance style that was grounded covertly in tantric worship (the maithuna offering) and overtly in the bhakti tradition of Vaisnavism;2 (e) he was aware of the ambiguity in his societal position, presumably strong being a male and weak being brought up by Maharis, by now associated with temple prostitution; and (f) he was operating in a society fraught with gendered power dynamics.

The portrayal of the women in the Pancha Kanya dances, uneasily combining all these factors, has resulted in an ambiguity that is also the strength of the dances. Second, the shift within each one of the episodes culminating in a compromise or an affirmation is clearly evident, although in some the shift is more obvious than in others. Third, the sthayi bhava abhinaya that often belies the words in the text and sometimes contradicts them reveals the growing ambivalence in the position of the Maharis in society today and since the time the script was written. According to the guru, he inherited the script, written by Kishore Kabi Shyam Sundar Kar, from his aunt, Ratnaprabha Devi, a well-known devadasi in her time.

The Pancha Kanya dances also play with the connotation of the words sati, mahasati, and sattvika as applied to women who were considered to be fallen by the mainstream society. In the context of the Maharis whose lives are “auspicious” although they are supposedly “impure” and beyond the pale of caste, the emphasis on the notion of being fallen/impure and virtuous/auspicious simultaneously is significant.4 An analysis of the script and the dance rendition will enable us to see these ambiguities better. There is a common introduction to all of the Pancha Kanya dances: the introduction begins with the “Angikam” sloka of Lord Shiva and continues through a rhythmic tandava to an invocation of Usha, the Goddess of Dawn. However, in spite of part of the invocation addressing Goddess Usha, Guru Pankaj Charan Das choreographed the rising of the sun and incorporated “Vibhupada trata”, thus conceding to the male supreme.

The next phase of the dance is in Oriya, rather than in Sanskrit and is sung by a woman:

Alosyo porihoro/ onusoro dhormo/ sonsoyi somsaro otibo durgomo/ poncho bhuto khiti optejo moruto byomo/ poncho soti nirjyaso gyani bodhogomyo/ Oholya, Droupodi, Kunti, Tara Mondodori totha/ Poncho soti smore nityo Moha patoko nasonom. (Cast aside your languor, follow dharma, and overcome the vicissitudes of samsara by meditating on the five women who symbolize the five elements.)

This phase clearly equates the five elements with the five women: Ahalya born of water, Draupadi born of fire, Kunti born of earth, Tara born of wind, and Mandodari born of ether. All sins will be washed away if one meditates on these five “virtuous” women, with emphasis on the “virtuous” not the “fallen” as the master narrative would have it. The use of Oriya too is significant here: it is Guru Pankaj Charan Das’ rejection of the Sanskritic tradition, embracing of the embedded tantric philosophy in Mahari dance at the temple of Lord Jagannatha, coupled with the integration of the marginalized into that patriarchal tradition, even as he celebrates the females in these two epics.

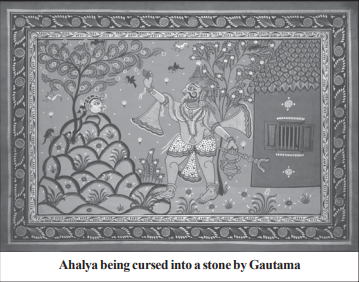

After these two segments, the dance of the specific kanya begins. Here, I will recount and summarize the stories of the five females as portrayed in the dances. Ahalya, the beautiful wife of the sage, Gautama, created as a rival to Urvashi, was coveted by Lord Indra, King of the Heavens. After getting Gautama out of his way, Indra disguised himself as Gautama and made love to Ahalya. Gautama divined the deception, and in his anger, returned, poured sacred water into his hand, and cursed her into becoming stone. Ages later, the sage Vishwamitra brought young Rama (and Lakshmana) to Ahalya’s statue to redeem her.

After these two segments, the dance of the specific kanya begins. Here, I will recount and summarize the stories of the five females as portrayed in the dances. Ahalya, the beautiful wife of the sage, Gautama, created as a rival to Urvashi, was coveted by Lord Indra, King of the Heavens. After getting Gautama out of his way, Indra disguised himself as Gautama and made love to Ahalya. Gautama divined the deception, and in his anger, returned, poured sacred water into his hand, and cursed her into becoming stone. Ages later, the sage Vishwamitra brought young Rama (and Lakshmana) to Ahalya’s statue to redeem her.

The dance drama begins with a description of Ahalya. The supposedly fallen woman, Ahalya, is described as a sensous and beautiful but pure woman, who is beloved of the Earth. She takes refuge at the feet of her husband, Gautama, who despite his love for her curses her to stone when he discovers she had made love to Indra. This woman sees him return earlier than usual and immediately proceeds to wash his feet. She does not know that the man is Indra in disguise. When her real husband returns in rage, Ahalya looks from one to the other, bewildered and aghast. The subsequent curse is juxtaposed against this innocence, love, and deception by Indra, underscoring the injustice of the curse. That Indra was also cursed in the epic is not shown in the dance item. Neither is there any indication that Ahalya may have been complicit in the action. Ahalya’s curse, thus isolated, becomes a masterful indictment of a society where a woman, and a subservient, dutiful one at that, is condemned for no fault of hers, and the victim is blamed for the lust of a god, while the god is not questioned. The blaming of the victim by Brahmin patriarchy has been a reality in the lives of the Maharis in the past century.

At the end, when Rama is asked by Vishvamitra to redeem Ahalya with the touch of his feet, Rama responds, “Jugo probuddha e Oholya soti/ patoko orjibi kori oniti.” “Through ages, this is the sati Ahalya; if I arouse her, or commit the immorality, I will earn (commit) sin.” Ahalya, and by extension the Maharis, are extolled by Rama (an incarnation of Lord Visnu) as virtuous. Here, we find the ambivalence of indictment by Vedic society through the curse, and acceptance by Vaishnavism, the religion of the personal god who understands, through Rama. Assured by Visvamitra, Rama finally does as he is told. It is not until the speech of Rama that we see the question of morality and virtue being openly raised and Ahalya exonerated. Even so, the affirmation of Ahalya’s virtue is tentative since the question of rape and victimization is alluded to and not asserted or probed. Even the questioning of her virtue is obviously gendered, and is parallel to society’s indictment and castigation of the Maharis.

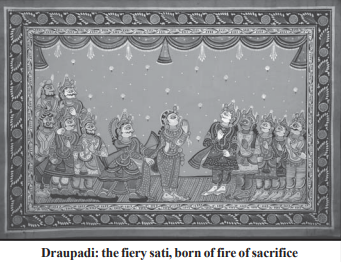

In Draupadi, Guru Pankaj Charan Das was bolder in his choreographic vision and interpretation of text. Draupadi was the wife of the five Pandava brothers. The story that is pertinent to the dance drama relates to the time when Yudhishthira, the oldest of the Pandava brothers, was invited to a so-called friendly dice game by his cousin, the Kaurava King, Duryodhana, who had rigged the game with his crooked uncle, Shakuni. Yudhishthira lost everything, even his brothers, when he pawned his wife. He lost her and his kingdom. In the dance, the scene begins with Dushasana dragging Draupadi into court. The court in this dance drama consists of Duryodhana, Dhritarashtra, Dronacharya, Bhishma, and Shakuni. Strikingly missing from this scene is Karna. The presence of Karna would have raised class issues uneasily intersecting gender issues. In the lives of the Maharis, caste, class, and gender issues are integrated. Hence, Karna’s absence allowed the Guru to proceed with his delineation of gender constructs more easily.

Draupadi is described as born of fire of s acrifice, one who has five husbands, daughter of Dhrupada, fiery sati, one who is purified of “adharma”, loved by Krishna, and dark complexioned. The dice game and the loss of the kingdom are followed by Draupadi commanding Dushasana to stop plaguing her while she speaks to her husbands. To Yudhishthira she asks what he will do as Dharmaraja (King of Dharma or Righteousness) now that she has been dragged into the court like a prostitute. His silence takes her to Partha. Pleading tearfully, Draupadi says, “You are the son of Indra, the second Krishna, the jewel of the Earth, see what trouble I am in.” There is no tearful pleading as she goes to Nakula. “You have might. You wear clothes made in the svargaloka. In this court, Dushasana is disrobing me. How can you bear it?” There is a feistiness that increases as Draupadi goes to Sahadeva. “You are the one that knows of all three kala — the past, present, and future. With all of this power, did you not know before that I would be in trouble?” Finally, she challenges Bhima. “With a hero like you [for a husband] I am in such sorrow. Watching Dushasana pull my hair, how can you not be angry?”

acrifice, one who has five husbands, daughter of Dhrupada, fiery sati, one who is purified of “adharma”, loved by Krishna, and dark complexioned. The dice game and the loss of the kingdom are followed by Draupadi commanding Dushasana to stop plaguing her while she speaks to her husbands. To Yudhishthira she asks what he will do as Dharmaraja (King of Dharma or Righteousness) now that she has been dragged into the court like a prostitute. His silence takes her to Partha. Pleading tearfully, Draupadi says, “You are the son of Indra, the second Krishna, the jewel of the Earth, see what trouble I am in.” There is no tearful pleading as she goes to Nakula. “You have might. You wear clothes made in the svargaloka. In this court, Dushasana is disrobing me. How can you bear it?” There is a feistiness that increases as Draupadi goes to Sahadeva. “You are the one that knows of all three kala — the past, present, and future. With all of this power, did you not know before that I would be in trouble?” Finally, she challenges Bhima. “With a hero like you [for a husband] I am in such sorrow. Watching Dushasana pull my hair, how can you not be angry?”

Seeing the hardheartedness of the Pandavas, Mahasati Draupadi invokes Krishna. In her last words, the fieriness and the feistiness of Draupadi evaporate as she pleads, “Come to give assurance to the poor/the destitute.” Here, there is a prolonged “suspension of disbelief” as the harasser, Dushasana, is frozen, while Draupadi recounts how she was won by Arjuna and lost by Yudhisthira. This pause was necessary for the guru to give epic qualities to the character of Draupadi. It also emphasizes the female as a pawn to the wiles of the male, contrary to the matrilineal Devadasi traditions. As the drumming begins, Guru Pankaj Charan Das visualizes Draupadi letting go of herself and stretching out both her hands. It is at this moment that Krishna appears, when the human soul has given in to him completely. According to Rittha Devi, at that time “Gone was the serene detachment with which he beheld human sufferings.

He rose to Draupadi’s rescue.”5 This was the personal God of the Maharis, the God who did not need to be owned. Again, we see an ambivalence in the depiction of Draupadi. Her strength when she says, “Wait, wait, Dushasana,” and stops him on his tracks, when she challenges her husbands, evaporates as she becomes more vulnerable and at the end gives up in complete surrender.

In the characterization of Draupadi there is a syncretism of the powerful Tantric goddess (particularly since Draupadi was menstruating at the time) with the sakhi bhava of Vaishnavism, the ultimate relationship of unpossessive love with her God as Dungri Mahari would call it. But there is also an inability on the part of Guru Pankaj Charan Das to follow through with his challenge of patriarchal images of the female. Freezing Dushasana also underplays the theme of sexual harassment even as the Guru builds up to it through Draupadi’s words to her husbands. He raises the questions, and this time, in contrast to Ahalya, voices them clearly, but ultimately gives in to the postulates of mainstream thoughts and beliefs as Draupadi becomes vulnerable and pleads with Krishna.

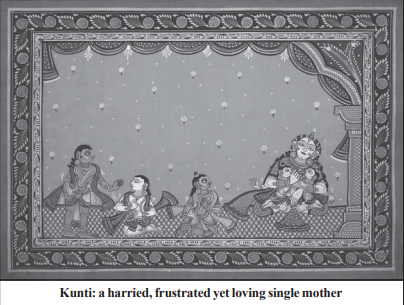

Kunti, the next kanya, was the mother of the Pandava brothers. But before she conceived them, she had a son, Karna, out of wedlock. She could not keep Karna, and the abandoned baby was found by a charioteer who brought him up. Eventually, Kunti was married to Pandu who had been cursed by a sage that he would die if he ever made love to a woman. Through the use of beads given to her by the sage Durvasah, Kunti conceived three sons, and when her husband’s second wife Madri killed herself for having caused their husband’s death, Kunti inherited the twins, Nakula and Sahadeva (who were begotten with the help of her beads).

Kunti opens with a pallavi, followed by the coming of the sage Durvasah, and Kunti’s service in which she is “most excellent.” Pleased with her “service” the sage gives her a garland [of beads] that will fulfill her desires in love. A brief introduction of Kunti as a person culminates with the phrase “meditate on Kunti every morning”. Then comes the scene where Kunti sees the rising sun and, curious in her nectar-filled kama or desires, she of the enactment of the abandonment of Karna has all the elements of indictment of the injustice of societal morality that condemns a woman for pre-marital sex. The scene changes to Pandu in the forest, hunting deer, the curse that Pandu can never make love to any woman, and Pandu’s despondence. Kunti gets dressed for her wedding. She is considered “an auspicious woman”,6 but she is also the woman who has “had pause or cessation in the enjoyment of wifely pleasures” by Agnika’s curse. She is ordered by her husband to save the lineage. After this, as usual, Guru Pankaj Charan Das narrates the story in an understated manner. When Kunti conceives the other children, there is no overt depiction of lovemaking. By offering her body, mind, and soul at his feet, keeping Dharma as witness, the chaste and faithful Kunti obtains a son in the presence of Dharma. That is as close as it comes to virgin birth. By subjugating the WindGod, the sati conceives Bhima — “ayotto kori”; the subjugation is a powerful image in delineating the character of Kunti. When enclosed by Indra, she receives Partho. The dance movements show Indra and Kunti together, not making love, but being in love. There are clear implications in the choreography that there was physical love, and yet it is emphasized again and again that Kunti was a “sati”, a “mahasati”.

Kunti is a mahasati as she was blessed with five sons that she nursed — those are the words of the song. The last scene in the dance depicts her as a single mother, harried, frustrated, and yet loving. The emphasis on the strength it takes to raise five rambunctious kids as a single mother is the Guru’s tongue-in-cheek indictment of the warped values of a society that cannot value the strength of a single mother raising five sons, and instead gives credence to the sons as heroes. Yet his indictment is phrased carefully and is veiled.

Tara, the fourth kanya, was the wife of Vali, the King of the Monkeys, and the mother of Angada. She tried in vain to dissuade her husband from fighting with Rama and Sugriva, her husband’s brother. When Vali died at the hands of Rama, Tara married Sugriva. The performed text has a distinctly different flavor. The dance drama, Tara, opens with a description of the antagonist, Rama. Rama, Laksmana, Sita, and Hanumana are brought to life and propitiated. Rama is hailed as one who is loved by all the people as the killer of Ravana. Then Tara is introduced. She is one who is “savarna” as the haughty one is Vali. Initiated in patience and forbearance, surrounded by followers, with a son, Angada, Tara is thoughtful, clever, resolved, virtuous, and one who surmounts difficulties. These descriptions are followed by the battle between Vali and Sugriva. After Rama shoots Vali from behind a clump of bushes, Tara rushes in to find herself widowed. She realizes that her husband was killed through deceit. She challenges Rama and accuses him of making her a widow. The language shifts back and forth between Sanskrit and Oriya as she concludes, “I have lost the boundaries of your wrong decisions.” She accuses Rama of proclaiming victory irrespective of whether he kills a monkey or a woman, such as Taraka. It is significant that of all the Rakshasas Rama killed in the course of his life, Tara zeroes in on Taraka who as a female powerfully controlled her region of the forest and kept the patriarchal Brahmin sages at bay.

Tara, the fourth kanya, was the wife of Vali, the King of the Monkeys, and the mother of Angada. She tried in vain to dissuade her husband from fighting with Rama and Sugriva, her husband’s brother. When Vali died at the hands of Rama, Tara married Sugriva. The performed text has a distinctly different flavor. The dance drama, Tara, opens with a description of the antagonist, Rama. Rama, Laksmana, Sita, and Hanumana are brought to life and propitiated. Rama is hailed as one who is loved by all the people as the killer of Ravana. Then Tara is introduced. She is one who is “savarna” as the haughty one is Vali. Initiated in patience and forbearance, surrounded by followers, with a son, Angada, Tara is thoughtful, clever, resolved, virtuous, and one who surmounts difficulties. These descriptions are followed by the battle between Vali and Sugriva. After Rama shoots Vali from behind a clump of bushes, Tara rushes in to find herself widowed. She realizes that her husband was killed through deceit. She challenges Rama and accuses him of making her a widow. The language shifts back and forth between Sanskrit and Oriya as she concludes, “I have lost the boundaries of your wrong decisions.” She accuses Rama of proclaiming victory irrespective of whether he kills a monkey or a woman, such as Taraka. It is significant that of all the Rakshasas Rama killed in the course of his life, Tara zeroes in on Taraka who as a female powerfully controlled her region of the forest and kept the patriarchal Brahmin sages at bay.

The dance choreography then shows a thoughtful Rama. He tells her that Vali was a womaniser, who needed to be killed. He asks her to accept Sugriva as her husband. The next part in the written script showed Rama embracing the bereaved Angada, son of Tara and Vali, and consoling him. Since the final rendition of the dance drama leaves out the words in the script, in an abrupt transition, Tara accepts Sugriva as her husband and asks for Rama’s blessing and, “with complete devotion”, bows at the feet of the Lord.

The change is very abrupt, particularly in light of the fact that Tara was depicted as a strong-willed woman and her challenge of Rama was full of anger. However, if we consider having an encounter with the Godhead as a prerogative to “kanyahood”, Rama appearing before Tara in itself implies strength. If, on the other hand, we follow Dr Chaturvedi’s lead of interpreting kanyahood as spiritual strength, leading to independence, Tara is a strong female. When we add another layer, that of Tara warning Bali of an alliance between Sugriva and Rama and Bali ignoring her warning, resulting in his death, we find even greater strength in Tara. The truce with Rama would imply a truce between the Aryan and the Vanara races, thereby leading to her own reestablishment as royalty. According to Bhattacharya, “Tara and Mandodari are parallels. Both offer sound advice to their husbands who recklessly reject it and suffer the ultimate consequence… Then both deliberately [italics mine] accept as their spouse the younger brother-inlaw responsible for the deaths of their husbands. Thereby, they are able to keep the kingdom strong and prosperous as allies of Ayodhya, and continue to have a say in governance. Tara and Mandodadri can never be described as shadows of such strong personalities as Bali and Ravana.” The dance rendition ends with a reiteration of Rama’s decision to proclaim Tara through the centuries as a “mahasati”. Tara remains Guru Pankaj Charan Das’ strongest challenge against patriarchy since it is only in this “kanya” that he voices sentiments questioning Rama. However, in its practicality, the dance loses its momentum at the end, with the acceptance by Rama being long and drawn-out, making the dance somewhat repetitive and tedious. The repetition of “Ajodhyaro sutroma”, proclaiming Tara a “mahasati”, seems to be the Guru underscoring Tara’s strength in making an alliance with Rama for her own benefit, following Bali’s death. Or, it could be that the Guru is proclaiming that Rama, the righteous king in mainstream Hindu ideology, speaks of Tara as a “mahasati”, and hence who are the people in the “samantavadi yuga” to question it? The last kanya, Mandodari, was Ravana’s wife, the antagonist in the Ramayana. She was transformed from a frog into a beautiful maiden with a less than perfect udar (belly). She was to distract Ravana from abducting the Goddess Parvati. In spite of all her pleading, Mandodari was unable to save the mortal Ravana because his death in the hands of Rama was the sole means of salvation for his soul.

The dance drama, Mandodari, opens with the depiction of Ravana in battle gear. Then there is a flashback as young Ravana and Mandodari as the frog maiden are introduced. Their love (sudhasneha) is emphasized. This section is followed by a musical segment portraying Mandodari’s unusual birth: a frog that lived in the sage’s ashram watched a snake poison the milk of the sage. The frog jumped in to save the sage from being poisoned; on his return, the sage was irate at first and cursed the frog because he surmised that the frog had yearned for his milk. However, the curse released the frog from a previous curse, and she transformed into a beautiful maiden. The depiction of the kanya, in the tradition of Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, and Tara before her follows: Mandodari, the daughter of Maya Daitya, “mandogamini” (slow of gait), beloved of Bali, and also beloved of the greatest of the family of Rakshasas, descendants of Nikasha Rakshasi, Ravana. Then the tension between Bali and Ravana for Mandodari and her being split in two causing her “udar” to be less than perfect is dramatized. the three worlds, similar to Yama, as Lord of Golden Lanka. Having the excellence of Rama in yoga, Vedas, shastras, and in the protection of Raghukula, Ravana is extolled. The scene shifts to one of Mandodari and Ravana in love. It is a touching scene, particularly when juxtaposed against her dressing Ravana for battle, having heard the “bedobani” that Ravana will have to die at the hands of Rama. Ravana addresses Mandodari and asks her not to decline his wish to offer his head at the feet of Rama. He will obtain “brahmando”, ultimate salvation by declaring Rama his enemy and dying at his hands. With tears in her eyes, Mandodari, “sulokhyoni Lonkarani” (auspicious Queen of Lanka), dresses her husband for battle. In the next scene the dance comes full circle as Ravana is at war with Rama, culminating in Ravana’s death. At this point the majesty of Mandodari emerges as she heroically watches her husband and Lanka destroyed. However, as Lankarani, the Queen of Lanka, she declares a truce with Rama, who requests Bibhisana, Ravana’s brother, to marry the virtuous Mandodari.

The dance drama, Mandodari, opens with the depiction of Ravana in battle gear. Then there is a flashback as young Ravana and Mandodari as the frog maiden are introduced. Their love (sudhasneha) is emphasized. This section is followed by a musical segment portraying Mandodari’s unusual birth: a frog that lived in the sage’s ashram watched a snake poison the milk of the sage. The frog jumped in to save the sage from being poisoned; on his return, the sage was irate at first and cursed the frog because he surmised that the frog had yearned for his milk. However, the curse released the frog from a previous curse, and she transformed into a beautiful maiden. The depiction of the kanya, in the tradition of Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, and Tara before her follows: Mandodari, the daughter of Maya Daitya, “mandogamini” (slow of gait), beloved of Bali, and also beloved of the greatest of the family of Rakshasas, descendants of Nikasha Rakshasi, Ravana. Then the tension between Bali and Ravana for Mandodari and her being split in two causing her “udar” to be less than perfect is dramatized. the three worlds, similar to Yama, as Lord of Golden Lanka. Having the excellence of Rama in yoga, Vedas, shastras, and in the protection of Raghukula, Ravana is extolled. The scene shifts to one of Mandodari and Ravana in love. It is a touching scene, particularly when juxtaposed against her dressing Ravana for battle, having heard the “bedobani” that Ravana will have to die at the hands of Rama. Ravana addresses Mandodari and asks her not to decline his wish to offer his head at the feet of Rama. He will obtain “brahmando”, ultimate salvation by declaring Rama his enemy and dying at his hands. With tears in her eyes, Mandodari, “sulokhyoni Lonkarani” (auspicious Queen of Lanka), dresses her husband for battle. In the next scene the dance comes full circle as Ravana is at war with Rama, culminating in Ravana’s death. At this point the majesty of Mandodari emerges as she heroically watches her husband and Lanka destroyed. However, as Lankarani, the Queen of Lanka, she declares a truce with Rama, who requests Bibhisana, Ravana’s brother, to marry the virtuous Mandodari.

In Guru Pankaj Charan Das’ subjective selection of the padas he manipulates Rama out of the script, as he did Karna in Draupadi. The result of this exclusion is the humanization of Ravana through his various interactions with Mandodari, including the incredible love scene and his pleading with her to prepare him for his final battle, his exit from life. The last segment, as Mandodari emerges in all her regal bearing as Lankarani is powerful, and yet in juxtaposition with her fulfilling her wifely duties contradictory. She marries Bibhisana so that she can remain Lankarani, and as Lankarani she makes an alliance with Lord Rama, her late husband’s enemy. Dr. Bhaduri spoke of this strategic alliance between the Aryan and the Rakshasa races.7 Thus we see that it is in Mandodari that Guru Pankaj Charan Das finally comes to uneasy terms with the assigned role of the female in a patriarchal society. Yet, at the same time, he does not completely accede to the societal codes. Mandodari emerges strong at the end, in spite of the acquiescence to patriarchy in her role as a model wife. Mandodari as Lanka Rani is emphasized, repeated to indicate her role as a strategist after her husband’s death.

Mandodari is a brilliant final statement for a marginalized Guru who constantly longed for the center stage. It is also amazing that the Guru, through his own intuition of marginalization, was able to dramatize Tara and Mandodari, representatives of the Vanara and the Rakshasa races, as two of the most powerful heroines, making alliances with the Aryan prince, Rama. However, in real life the Guru died as an alternative narrative in Odissi dance, uncompromising with the master narrative, the centre.

With Mandodari, Guru Pankaj Charan Das came full cycle. While Ahalya was feeble in her protest, Draupadi became more vocal in her challenges. Kunti, in spite of being the most transgressive of them, fitted squarely into the role of the mother of sons, but also emerged as an agent in the lives of her sons, enabling her at the end. Tara was stronger, more vocal in her questioning of patriarchy. However, by the end, she succumbed to her need for truce with Rama. The Pancha Kanya culminates with Mandodari voicing the power of the marginalized on the one hand, emerging as Lanka Rani, but being revered as “sohodhormini”, the dutiful wife on the other, closely aligned with Ahalya, the wife of Gautama. The sudden change in the political stand that characterized the conclusion of Tara finally turned into an acceptance in Mandodari, as a wife in patriarchal society, albeit as “Lanka Rani”. The contradiction in Guru Pankaj Charan Das’ vision is paralleled by the position of the matrilineal, matrifocal Mahari/Devadasi tradition, including the dances, in the patriarchal society today. The Devadasi institution may not live, but the questioning narratives of their matrilineal and matrifocal traditions will live through the Pancha Kanya and other dances. The power of the dance style is regal, sensuous, and spiritual, a testimony to the strength of women in India’s past.

With Mandodari, Guru Pankaj Charan Das came full cycle. While Ahalya was feeble in her protest, Draupadi became more vocal in her challenges. Kunti, in spite of being the most transgressive of them, fitted squarely into the role of the mother of sons, but also emerged as an agent in the lives of her sons, enabling her at the end. Tara was stronger, more vocal in her questioning of patriarchy. However, by the end, she succumbed to her need for truce with Rama. The Pancha Kanya culminates with Mandodari voicing the power of the marginalized on the one hand, emerging as Lanka Rani, but being revered as “sohodhormini”, the dutiful wife on the other, closely aligned with Ahalya, the wife of Gautama. The sudden change in the political stand that characterized the conclusion of Tara finally turned into an acceptance in Mandodari, as a wife in patriarchal society, albeit as “Lanka Rani”. The contradiction in Guru Pankaj Charan Das’ vision is paralleled by the position of the matrilineal, matrifocal Mahari/Devadasi tradition, including the dances, in the patriarchal society today. The Devadasi institution may not live, but the questioning narratives of their matrilineal and matrifocal traditions will live through the Pancha Kanya and other dances. The power of the dance style is regal, sensuous, and spiritual, a testimony to the strength of women in India’s past.

Footnotes

1. Dash, Dhiren, 1976 Catara, Jathara, Jatra-the Theatre. Bhubaneswar: Kwality Press.

2. For the Jagannatha Cult, see Eshmann, Kulke, and Tripathi, (1978, The Cult of Jagannath and the Regional Tradition of Orissa. New Delhi: Manohar.), see Bharati (1965, The Tantric Tradition. London: Rider & Company.), and Mookerjee & Khanna (1977, The Tantric Way: Art, Science, Ritual. Delhi: Vikas Pub. House.)

3. Barbara Curda has done intensive work on gender issues. See, Curda (2002, “Odissi in Contemporary Orissa: Strategies, Constraints, Gender,” in Dance As Intangible Heritage: Proceedings of the 16th International Congress on Dance research, Corfu. Greece: International Organization of Folk Art.)

4. Marglin, Frederique Apffel, 1985 Wives of the God-King. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

5. Devi, Rittha, 1968, “Panchakanya: A Rare Item in the Odissi Dance,” in Illustrated Weekly of India, March 3, 21.

6. For the mahari as an “auspicious” woman, see Frederique Marglin, The Wives of the God-King, 1985.

7. Bhaduri, Nrisinhaprasad, 2003, “Panchakanyas as Mahapatakanashini with special reference to Tara and Mandodari,” paper presented in the national seminar on Pancha Kanyas of Indian.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This is an edited version of a paper presented at the Second International Conference on Religions and Cultures in the Indic Civilisation organised by CSDS and Manushi from December 17- 20, 2005 The author is Senior Professor of Dance and Expressive Arts at The Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington, US. She is also a senior disciple of Late Padmashri Guru Pankaj Charan Das. The pictures are patta chitra paintings of the Pancha Kanyas from Raghurajpur in Puri District.

https://withoutprescription.guru/# buy prescription drugs without doctor

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexico pharmacies prescription drugs – buying prescription drugs in mexico online

https://canadapharm.top/# canadian mail order pharmacy

can you get cheap clomid without rx: cost of clomid – can i purchase clomid

canadian pharmacy world reviews: Certified and Licensed Online Pharmacy – online canadian pharmacy review

https://canadapharm.top/# canadian pharmacy no scripts

buy prescription drugs online legally: ed prescription drugs – п»їprescription drugs

can you buy amoxicillin over the counter: amoxicillin generic brand – where to buy amoxicillin 500mg

canada drugstore pharmacy rx: Certified and Licensed Online Pharmacy – canadian pharmacy online

https://withoutprescription.guru/# meds online without doctor prescription

20 mg tadalafil cost canadian pharmacy generic tadalafil tadalafil 5mg in india

Kamagra Oral Jelly: Kamagra 100mg – cheap kamagra

https://tadalafil.trade/# tadalafil generic price

https://sildenafil.win/# price for sildenafil 100 mg

generic tadalafil medication: price of tadalafil 20mg – generic tadalafil 10mg

best online tadalafil tadalafil from india buy tadalafil 20mg price in india

Cheap Levitra online: Buy Vardenafil 20mg – Vardenafil online prescription

https://tadalafil.trade/# cost of tadalafil generic

buy tadalafil online no prescription where to buy tadalafil in singapore tadalafil 2.5 mg price

https://kamagra.team/# Kamagra tablets

tadalafil over the counter uk: tadalafil from india – tadalafil prescription

https://edpills.monster/# best ed pill

cheap kamagra: buy Kamagra – Kamagra 100mg price

new ed pills best ed pills at gnc ed medications list

https://levitra.icu/# Levitra tablet price

pills for ed: п»їerectile dysfunction medication – buy ed pills online

cipro online no prescription in the usa: Ciprofloxacin online prescription – ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet price

https://amoxicillin.best/# where can i get amoxicillin

where can i buy amoxicillin without prec amoxil for sale amoxicillin 500 capsule

prinivil tabs: buy lisinopril – cost of generic lisinopril 10 mg

antibiotics cipro: buy cipro online canada – buy cipro cheap

https://azithromycin.bar/# zithromax 500mg over the counter

buy zithromax without presc buy zithromax zithromax online australia

buy cipro online without prescription: Get cheapest Ciprofloxacin online – ciprofloxacin 500 mg tablet price

lisinopril 10 mg for sale: prescription for lisinopril – zestril discount

https://amoxicillin.best/# amoxicillin 500 mg tablets

buy generic ciprofloxacin buy ciprofloxacin online ciprofloxacin generic

can i purchase amoxicillin online: amoxil for sale – amoxicillin tablets in india

https://lisinopril.auction/# lisinopril brand name australia

cipro pharmacy ciprofloxacin without insurance ciprofloxacin order online

doxycycline cost united states: Buy Doxycycline for acne – buy vibramycin

antibiotic amoxicillin: amoxil for sale – amoxicillin azithromycin

https://doxycycline.forum/# order doxycycline online australia

amoxicillin 500 mg where to buy cheap amoxicillin amoxicillin 500 mg cost

amoxicillin for sale online: purchase amoxicillin online – amoxicillin without a doctors prescription

https://amoxicillin.best/# order amoxicillin uk

purple pharmacy mexico price list: mexican online pharmacy – mexico pharmacies prescription drugs

https://canadiandrugs.store/# reddit canadian pharmacy

canadain pharmacy no prescription: Online pharmacy USA – top rated canadian online pharmacy

mexican rx online: top mail order pharmacy from Mexico – mexico drug stores pharmacies

https://indiapharmacy.site/# indianpharmacy com

canadian mail order viagra: online pharmacy usa – legal canadian pharmacy online

canada online pharmacy reviews: buy prescription drugs online – discount prescription drug

reputable indian pharmacies cheapest online pharmacy india indian pharmacy

https://mexicopharmacy.store/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

overseas pharmacies shipping to usa: buy medication online – discount drugs canada

wellbutrin canadian pharmacy: Buy Wellbutrin SR online – wellbutrin xl

https://wellbutrin.rest/# order wellbutrin

wellbutrin online: Buy bupropion online Europe – wellbutrin discount price

https://claritin.icu/# ventolin otc canada

wellbutrin 75 mg tablet: wellbutrin 150 mg – wellbutrin online india

https://clomid.club/# where can i buy clomid without a prescription

paxlovid cost without insurance https://paxlovid.club/# paxlovid generic

can i buy generic clomid without a prescription: Clomiphene Citrate 50 Mg – can i purchase clomid no prescription

https://claritin.icu/# ventolin 4mg tab

https://wellbutrin.rest/# wellbutrin prescription uk

neurontin 600 mg price: buy gabapentin online – neurontin 150mg

https://clomid.club/# can i order generic clomid price

best generic wellbutrin 2017: Wellbutrin prescription – wellbutrin xl generic

https://gabapentin.life/# neurontin prescription coupon

acquistare farmaci senza ricetta: farmacia online spedizione gratuita – farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

acquisto farmaci con ricetta: kamagra gel – top farmacia online

https://kamagrait.club/# migliori farmacie online 2023

farmaci senza ricetta elenco avanafil farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

viagra online spedizione gratuita: viagra online spedizione gratuita – viagra naturale

acquisto farmaci con ricetta: cialis generico consegna 48 ore – migliori farmacie online 2023

farmacie online autorizzate elenco: avanafil spedra – farmaci senza ricetta elenco

farmacie on line spedizione gratuita: avanafil generico – acquisto farmaci con ricetta

farmacie online affidabili Avanafil farmaco farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: kamagra gel – farmacia online senza ricetta

https://tadalafilit.store/# farmacia online senza ricetta

comprare farmaci online all’estero: farmacia online migliore – farmacia online miglior prezzo

farmacia online migliore: farmacia online miglior prezzo – farmacie online affidabili

alternativa al viagra senza ricetta in farmacia: viagra prezzo farmacia – viagra originale in 24 ore contrassegno

comprare farmaci online con ricetta: kamagra oral jelly – farmacie on line spedizione gratuita